CLEVELAND! Long a major center of railroad and canal traffic, the Forest City now stakes its claim on its historic architecture, long-suffering sports teams, and hastily-made tourism videos proclaiming it to be "not Detroit". But among the misspellings (originally "Cleaveland", after land surveyor Moses Cleaveland, but shortened to fit the Cleveland Advertiser's masthead), railroad history (a major city on the Pennsylvania and New York Central Railroads), and cultural institutions (Rock & Roll Hall of Fame), Cleveland holds a place in the realm of electric railroads as one of the longest-running interurban systems in America (since 1913!). Today, we take a look back at the "Progress and Prosperity" that built up the Forest City and see if Cleveland still Rocks.

-----

Legal Troubles in C-Town

|

| Come on down to Cleveland town, everyone! Street railroad service since 1832! (Retro Cleveland) |

The first modern street railroad to run in Cleveland dates back to August 5, 1879, when the Kinsman Street Railroad (KSR) was granted a franchise (by city ordinance) to operate a "double track street railroad" between Superior Street to Madison Avenue, via Woodland Avenue (then Kinsman Street). Before that, street railways in Cleveland were an independent mishmash of suburban steam lines. The franchise was valid for 25 years, up until 1904, and further ordinances extended the KSR out to Corwin Street. By 1885, the KSR was gone and reorganized as the Woodland Avenue Railway Company (WARC), buying up the West Side Street Railroad Company and consolidating them in the process. This affair worried the city council, as under Ohio law they could choose to deny or accept the consolidation. On February 1, 1885, the city council approved the consolidation on the condition a "single fare... of the consolidated road no greater charge than 5 cents shall be collected". The terms of the original franchise for the KSR remained the same, still expiring in 1904.

| We had a cable car line for some reason! It didn't last long, we still can't think of why! (Cable Car Home Page) |

By the time January 11, 1904 (25 years after the franchise was granted) rolled around, the Cleveland Electric Railway Company (CER) was in deep legal trouble. Renamed in 1893 following the further consolidations of the Woodland Avenue & West Side (WAWS) with the Cleveland Cable Railway Company, the CER was sued by the city of Cleveland and the Forest City Railway (FCR) under the KSR's original franchise. The suit alleged that a city ordinance passed the charter to the FCR once it expired, and none of the CER's constituent companies had any franchise to their streets. When the lines switched from horse and cable to electric, the CER alleged the city granted the WAWS exclusive access to electrify its whole line, with the CER as the successor company. This was denied. When the legal rigmarole was finished, the court named the CER successor to the KSR franchise and gave the FCR a franchise extension until January 26, 1910.

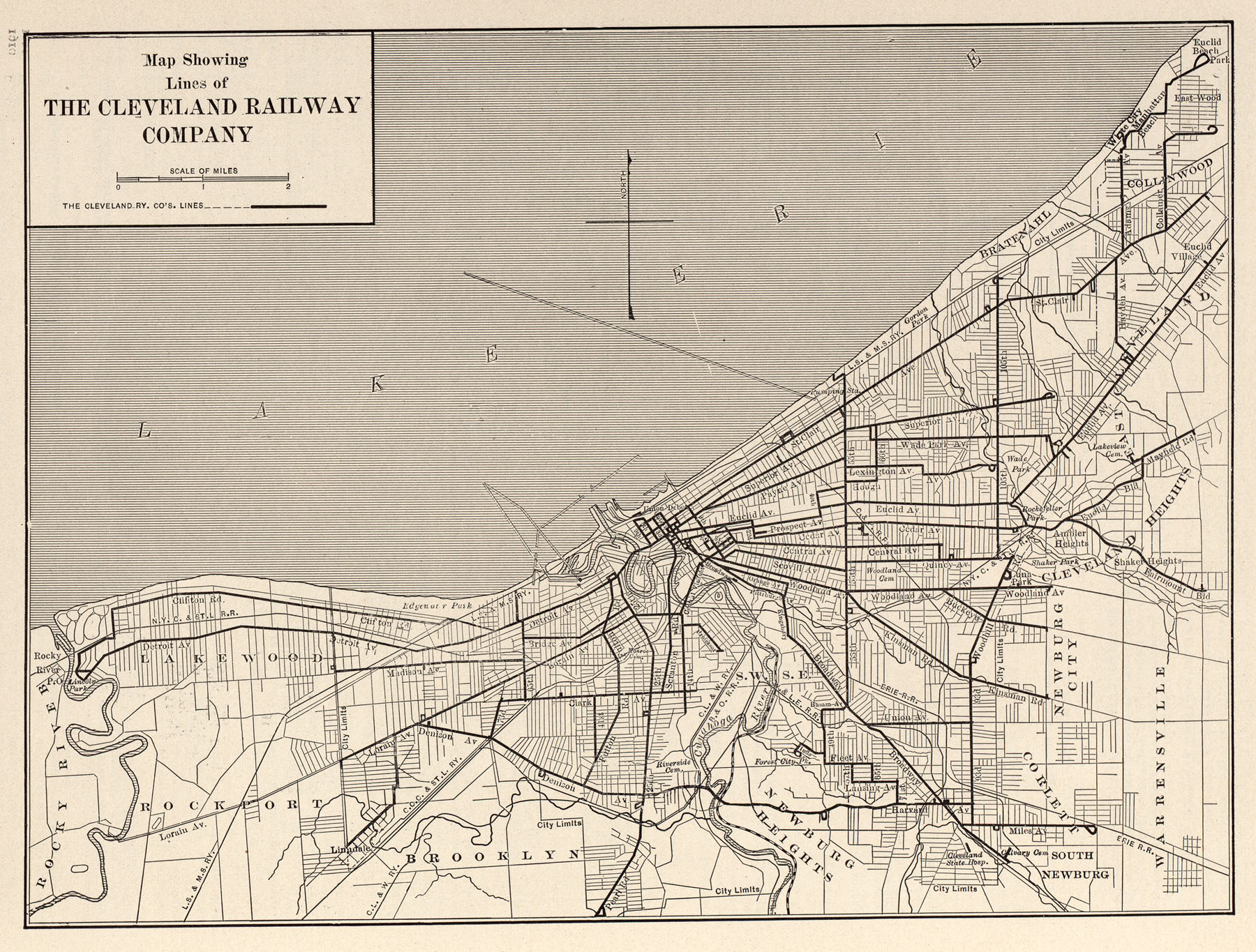

When 1910 came and went, the Cleveland Railway (CR) was finally formed, combining both the CER and FCR's assets into one pliant form. 425 miles of street railway track stretched east and west out of the city, with all lines converging on Cleveland Public Square. Lots of small towns were now connected to the CR, enabling more people to commute to the busy Port of Cleveland and build up trolley suburbs as far west as Rocky River Hamlet and east out to Warrensville and Newburgh Hamlet. Also building up the system were the many interurban lines that sprouted up and around Cleveland to connect out east to Chagrin Falls and Pennsylvania, and west along the southern Erie coast to Lorain and Oberlin.

|

| Watch our street railway grow with our city! There's surely no way they can bus this whole thing! (University of Texas Libraries) |

Shake 'Em Up, Boys

|

| A cartoon of our greatest benefactors, Mantis is left and Oris is on the right! (Hoovers World) |

One of the most famous of these interurbans was a nascent startup by two brothers, Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, called the Cleveland Interurban. Originating from the brothers' home in Shaker Heights, the Van Sweringens realized the local CR service to downtown was slow and crowded the roads to the city center. Eager to build Shaker Heights as a streetcar suburb, they established the Cleveland Interurban Railroad in 1913, but this quickly became known as the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit (SHRT) Using their majority stake in the local New York Chicago & St. Louis Railroad (better known as the Nickel Plate Road), the Van Sweringens not only had an instant private right-of-way along a steam railroad, but they also gained the capital needed to fund construction, as they only had enough to purchase a terminal location in downtown Cleveland.

|

| Tower City is really gigantic! It'd be perfect for a bad guy's headquarters! (Erik Drost) |

This terminal location proved to be a tricky puzzle for the Van Sweringens, as their "Public Square" station needed connections to all streetcar, rapid transit, and interurbans as well as local steam, freight, and warehouse railways. Under the guidance of several in-area railroads, the brothers planned a grand structure called the Terminal Tower to bring their interurban to completion three years after it officially opened. The Terminal Tower began construction in 1923 as part of the Union Terminal Complex, and was listed as the second tallest skyscraper in America at that time. The building was eventually completed in 1930, but while this happened, the Van Sweringens continued to build their railroad empire (owning railroads from New York to Michigan) and the SHRT grew in size, encompassing two lines along Van Aken and Shaker Blvds.

|

| Our interurban is really super old, but it appeals to railfans anyway! (Railfan44) |

Unfortunately, by the time the SHRT reached World War II, the Van Sweringens had gone bankrupt and the line was stagnating and financially struggling. Recognizing the importance of the "Rapid", the city of Shaker Heights assumed municipal operations of the railroad on September 6, 1944. Despite lacking funds for any significant extensions from Warrensville/Van Aken or West Green Green/Shaker Blvd, the city funded a large order of PCC Cars from St. Louis Car Company in 1946 and Pullman Standard in 1947. These cars became near-ubiquitous to the Shaker Heights, lasting longer than the 1920s lightweight cars they replaced, and all the way to the Cleveland Transit System (CTS) and the Greater Cleveland Rapid Transit Authority (RTA) in the 1980s. But, I'm getting ahead of myself.

Notable Rolling Stock

|

| Ok, gonna stop the gag here. This is Car No. 461, rebuilt by CR with closed sides despite being a Kuhlman "summer" car. (Weldon Thornquist) |

Since we're on the subject of rolling stock, let's take a brief aside and talk about the cars that made Cleveland Railway hum. Following the conversion to electricity, most of Cleveland's streetcars were tiny Brill single-truck cars from 1892. Uniquely, the CR also rostered a rebuilt summer car, No. 461, which had sides built into it for the more inclement times of year. The biggest class of cars came in 1914 with an order of GC Kuhlman Car center-entrance streetcars dubbed the "1200 Class". These were fast cars, able to generate 192 horsepower from its four Westinghouse 340 motors and were so populous they served both the CR and the center entrance construction influenced other carmakers like St. Louis to follow suit. Some of these cars were later rebuilt as one-man cars and a front entrance was added, while others were rebuilt as trailers for the Shaker Heights line. After the success of the Kuhlmans, Cleveland Railway commissioner Peter Witt immediately submitted his own design patent to GC Kuhlman the year after for a more efficiently-loaded streetcar with a front entrance and center exit. I'd say more, but that's a story for another time...

|

| The Lakewood carhouse in 1942, showing off the Kuhlman center entrances (center two) and the Peter Witt cars (outer two) with their front entrances. (Patrick Cooley, Cleveland.com) |

|

| A Cincinnati Lightweight car on the original SHRT, before being purchased by Speedwell. The "rubber stamp" curved sides added strength without compromising lightness. (Don Ross) |

On the much faster side, the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit was originally defined by its lightweight cars built by Cincinnati Car Company between 1928 and 1929, and by St. Louis Car in 1924. The older lightweights came from the Aurora, Elgin & Fox River Electric Company before being sold to the Rapid in 1936, while the newer ones by Cincinnati became more ubiquitous on the Milwaukee Speedrail system. What remained of these cars were replaced by the PCC cars of 1946 and 1947. A majority of these cars were the new "P3" class, integrating a canted windscreen with a built-in shade, standee windows, and a wider body construction to accommodate more passengers. What made some of these PCCs unique was the addition of a clerestory roof to hide the heating and forced air ventilation components from Pullman. The St. Louis Cars from 1946 were bought used from the Twin City Rapid Transit or the St. Louis Public Service and converted to multiple-unit working, while the Pullman cars were purchased new in 1947. When the CR ended streetcar service, most of these cars were sold to the Toronto Transportation Commission and re-gauged, while others went into preservation long after their service lives in the 1980s.

|

| Cleveland Railway No. 4201 in color, showing off the added clerestory roof. (Voogd075) |

The Stab in the Back

|

| An articulated Peter Witt Streetcar is crowded by buses on Euclid and East 102 in 1951 (Patrick Cooley, Cleveland.com) |

While the SHRT was able to be saved by a community that so needed it, the Cleveland Railway was not only shown the door but shafted on the way out. Starting in 1935, the railway began replacing its streetcar lines with buses and the citizens of Cleveland began to take notice that a lot of them, if not all of them, were GM buses or Marmon-Herrington trolley coaches. Worse still, the mayor and city councillors were seen in swanky new GM cars and this caused many citizen red flags to rise. It's worth noting that the infamous National City Lines never tried to buy the Cleveland Railway, but GM's actions forced the citizens to report this crony behavior to the FBI. Unfortunately, the FBI basically told Cleveland to "take a hike, or better yet take the bus" and refused to investigate due to the "high profile nature" of the people indicted. The Cleveland Railway was eventually purchased by the CTS in 1942 and after heavy bus conversion, the last streetcar ran on January 24, 1954.

The Legends Live On

|

| Two Windermire-bound Red Line trains stop at West Park, 1968. (David Wilson) |

Despite the Shaker Heights being municipally owned, there was no denying the infrastructure and rolling stock was old and tired. The CTS was busy overhauling the now-streetcarless city of Cleveland by opening up a new rapid transit line between Windermire and Hopkins International Airport in 1958. This made the CTS Red Line one of the first railed airport connections ever run in America, but it also brought with it major infrastructure issues. Due to sharing two stations with the Shaker Heights line, Tower City/Public Square and E. 34 Campus, the Red (Windermire/Airport) Line needed two platform levels to run both the higher, heavier rapid transit cars and the elderly PCCs still running the Blue (Van Aken) and Green (Shaker Blvd) lines. The Red Line also managed to bankrupt the CTS, with bus and rapid transit unable to recoup its losses despite being an essential line. In 1974, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) took over all municipal transit, with the Shaker Line absorbed on July 14, 1975. The colors were later announced on September 30 of that year.

|

| Illinois Terminal 450 and 451 rush along the severely- deferred Shaker Heights Line in 1978, note 451 (rear) is running as a trailer with its pole down. (Jim Strain) |

In inheriting the Shaker Heights line, RTA was now saddled with the task of rehabilitating the Blue Line from the ground up. Due to the mass-retirement of PCC cars under CTS, the Shaker Heights' remaining elderly PCCs were not enough to provide the line with adequate service, so the Cleveland RTA looked at museums around the country to find MU-capable PCCs to run the line as they renovated it. Luckily, the Ohio Railroad Museum and the Connecticut Trolley Museums had two, perfectly-restored, and MU-capable PCCs in the form of Illinois Terminal 450 and 451. Both cars were immediately shipped to Cleveland, reunited, and leased between 1976 and 1979 while the RTA figured out replacements. Unfortunately, shortly after they were leased, IT 450 was involved in a traffic collision that left it damaged and 451 was sent off to operate solo most of the time. Both cars were eventually returned and the PCC cars were replaced by new Breda LRVs between 1980 and 1981.

|

| The RTA's current system map, three lines over the Cleveland downtown area and its suburbs. (RTA) |

Today, the Cleveland RTA's "Rapid Transit" sector operates four rail and four trolley lines in and around downtown Cleveland. Aside from the Red, Green, and Blue Lines, the Waterfront Line is the most significant addition to the light rail system. Running between South Harbor and Tower City, the line serves as an extention of the Blue and Green north of Tower City, but is unique in name. The route follows an old New York Central alignment past the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and FirstEnergy Stadium (otherwise known locally as the Factory of Sadness). Future street running extensions have been offered to make the Waterfront line a loop, and connecting with the HealthLine rapid bus service, but nothing has stuck so far. Despite the aging equipment, the old lines, and the small footprint compared to what was before, it hasn't stopped the Cleveland RTA from being voted the best public transit service in America in 2007.

|

| The Waterfront Line and Blue/Green's light rail vehicles, built by Breda. (Eustacio Humphrey) |

| Cleveland No. 165 in its current display at the Henry Ford. (HeritageRail Alliance) |

Seventeen ex-Cleveland Railway passenger and MOW cars are now preserved along the Eastern United States in varying conditions, with the oldest being Brill streetcar/wrecker No. 165 from 1892. The car was rebuilt into a wrecker in 1903 and is now preserved at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, since 1904. Eight of the 1200 class center-entrance cars also survive at the Connecticut Trolley Museum (No. 1), Illinois Railway Museum (18), Northern Ohio Railroad Museum (12, 1203, 031, a greaser, and 2318, a trailer) Seashore Trolley Museum (1227 and 2365, a trailer), and Edmonton Radial Railway Society (202 and 203, Peter Witt streetcars). Some are in operable condition, with one even coming from the Cleveland RTA's heritage division until donated in 1982. Considering the huge amounts of survivors, it's safe to say that Cleveland's light rail history is in no chance of being extinct.

|

| It could be worse, you could be in... Detroit! Still not Detroit! (Ohio.org) |

-----

Watch your step as you alight onto the platform and thank you for reading with us! Local sources for this article included Cornell Law School's copy of the Cleveland Railway legal proceedings and the Cleveland RTA. If you would like to learn more about the museums mentioned here, follow the museum links for the Seashore Trolley Museum, the Northern Ohio Railway Museum, Connecticut Trolley Museum, Illinois Railway Museum, Ohio Railway Museum, and the Henry Ford. Also special thanks to Vicky of the Ohio Railway Museum for extra info about IT 450 and 451. On Thursday, we finish off the month by talking about one of the most ubiquitous streetcars in North America, and perhaps even the world: The Peter Witt Streetcar. Until then you can follow myself or my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe buy a shirt as well! Ride safely, now!

No comments:

Post a Comment