Tuesday, March 31, 2020

Trolley Tuesday 3/31/20 - The Denver Tramway

Denver, Colorado, is known for many things and by many names, boasting two successful sports teams, a beautiful Union Station building, and a demonic horse overlooking the massive tent city that is Denver International Airport. (Seriously, someone call the SCP Foundation on it.) What Denver also boasted was a massive, 160-mile interurban and streetcar system that remained privately run, and much loved, for almost 100 years, parts of which continue to operate today. So saddle up and get Rocky Mountain High, because Trolley Tuesday is turning its eye on the early years of the Denver Tramway!

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

Trolley Tuesday 3/24/19 - The Sheridan Streetcar

Our third and final Wyoming trolley adventure in March (because we couldn't fill it with enough content about Arizona) comes from the northern edge of the big square state! Sheridan, Wyoming, is certainly more remote than Laramie or Cheyenne, but it is nonetheless as important as the two when it comes to trolley history: not only did Sheridan have the only interurban line in the state, but it is also home to the only remaining streetcar in all of Wyoming. All of these and more on today's Trolley Tuesday!

The Main Street alignment would be known as the City Line, and after a successful operating period of five days, a second line would open dubbed the "Fort Line." This extension ran up Main Street and over Lewis Hill to the Sheridan County Fairgrounds, before heading out to Fort MacKenzie, a US Army outpost established in 1898. With two trolley lines operating at peak capacity over five streetcars, it was now time for an interurban line.

The line operated as a source of civic pride the rest of the 1910s with no major changes, just another small town streetcar, but the 1920s brought about major change. It wasn't the bus companies that killed the Sheridan streetcar, but rather a matter of practicality. Main Street was to be repaved in 1923, and the city council added that the double-track down Main would be removed due to declining ridership. In September 1923, the City Line was discontinued but that left the Fort street and Mine interurban lines operating.

-----

|

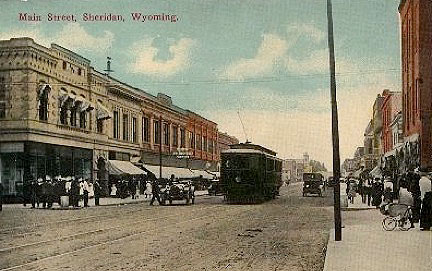

| Sheridan in 1909, prior to the streetcar installation. (Wyohistory.org) |

Sheridan, WY, lies 13 miles south of the Wyoming-Montana border within the same-named county. The town site was first inhabited in 1878 by trapped George Mantel, but the town would be officially established in 1882 and named after Civil War General Philip Sheridan of the Union Army. In the early days, railroad commerce fueled the small town thanks to the Burlington & Missouri Railroad (B&M, now Burlington Northern Santa Fe), but it was the discovery of rich coal mines that boosted Sheridan's status as a mining boomtown. By 1910, where this story begins, Sheridan boasted 18,000 citizens, but no train service to and from the mines.

|

| Burlington and Missouri Railroad No. 120 in Broken Bow, Nebraska, 1886. (Library of Congress) |

In 1910, two men from Dayton, Ohio named Albert Emanuel and William Sullivan, proposed giving Sheridan its own streetcar system that would also provide interurban service from the town to the mines, the only one in the state. Unlike the hornswoggling committed in Laramie, the city fathers trusted Emanuel and Sullivan enough to approve their proposal and contruction began on July, 11, 1910, finishing just a year and a month later on August 11 with a single line down Main Street from the Burlington & Missouri depot.

|

| A colorised image of Sheridan at night, with a tiny "Rubber Stamp" heading away. (Wyohistory.org) |

The new company, the Sheridan Railway & Light Company, was a welcome modernization to the town and on opening day, many crowded the streets to gaze at the new trolley cars. Three would be delivered that opening day from American Car Co. and came to be known as "rubber stamps" due to the short shape resembling a traditional stamp applicator. Car 10 would be draped in a fashionable banner reading "The Buisness Mens Club" as she rolled down Main Street, but nobody would bother to correct the spelling or grammar errors.

|

| Guys, this is literally what my editor is here for. (Downtown Sheridan) |

The Main Street alignment would be known as the City Line, and after a successful operating period of five days, a second line would open dubbed the "Fort Line." This extension ran up Main Street and over Lewis Hill to the Sheridan County Fairgrounds, before heading out to Fort MacKenzie, a US Army outpost established in 1898. With two trolley lines operating at peak capacity over five streetcars, it was now time for an interurban line.

|

| Sheridan's swanky interurban cars by American Car Co. of St. Louis, photographed October 1911 (Bill Volkmer) |

Dietz was located five miles north of Sheridan, with the line north following the B&M's mainline out to Montana. The mine entrance was too far for the railroad to change its alignment, so the interurban was built to haul workers to and from the mines much more conveniently. The route would add another 12 miles to the Sheridan system and large wooden interurbans from American Car to the boomtown's fleet.

|

| Another postcard shot of 1912, showing the Mine Interurban on Main Street, looking North. (Wyohistory) |

|

| A Main Street Postcard of Sheridan in the late 1920s, showing a distinct lack of trolley track or wire. (HipPostcard) |

March 1924 would see the Fort Line give up the ghost when it was replaced by bus service, and the Mine interurban would be abandoned in 1926, giving it the distinction of being the last electric railway in the state of Wyoming. Though Sheridan continues today as a quiet little mountain town full of buses, the Sheridan Electric Lives on when the body of city car 115 (itself an original American Car Co. product) was found lying in a field. Today, the Sheridan County Museum has the car plinthed outside their location where it was first restored in 1976.

|

| Sheridan Electric and Light Co. No. 115, the last trolleycar in Wyoming. (The Sheridan Press) |

Car 115 underwent a quick restoration for America's bicentennial, including slipping two AAR freight trucks below its original steel frame. Today, the Sheridan College Welding Department and the Sheridan County Museum are working to make a new steel base to sit the original body on (complete with facsimile wheels) and give the 115 a new lease on life.

-----

Thank you for reading today's Trolley Tuesday postings! As a minor surprise, this is the last episode in March as we've... run out of content, so Thursday will be have no postings. Fret not, however! Starting March 31, we move over to our next state: Colorado! You won't believe how much trolley content we get to mine from there! Until next time, follow myself and my editor on Twitter, go buy a shirt, and ride safe!

Thursday, March 19, 2020

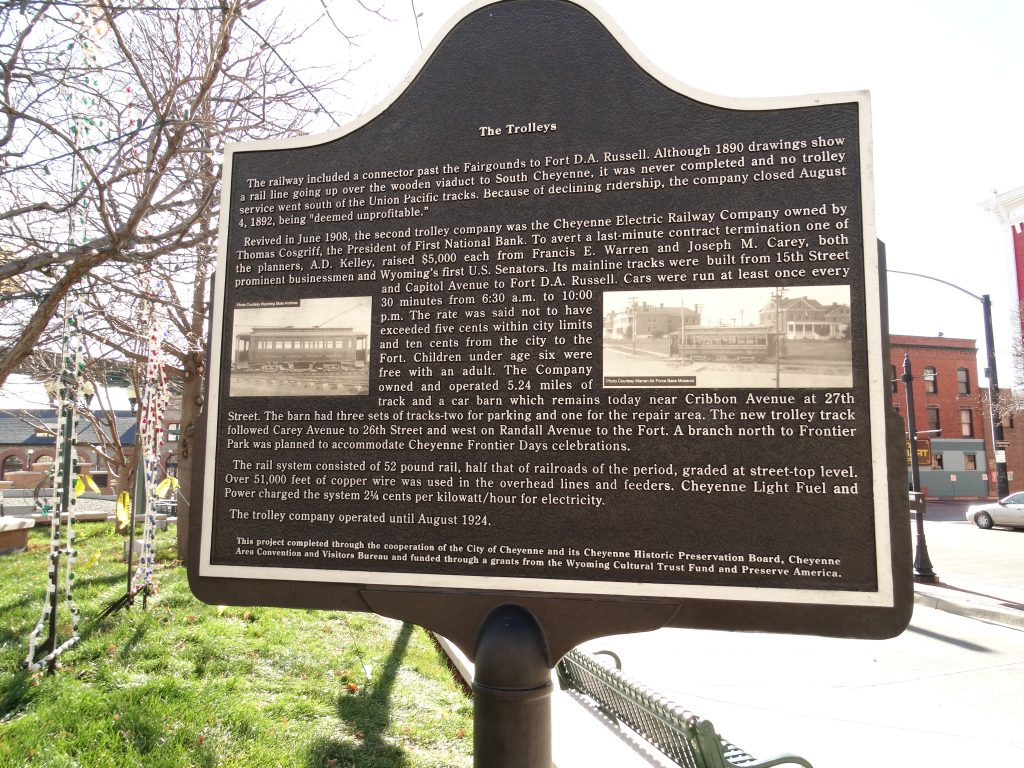

Trolley Thursday 3/18/20 - Cheyenne Electric Railway Co.

Welcome back to Trolley Thursday, where today we'll be looking at the capital city of Cheyenne, Wyoming. The city needs no introduction to railfans as it's famous for housing the Union Pacific railyard and maintenance facility that houses steam locomotives 844, 3985, 4014, and 5511, as well as a sprawling diesel complex. While UP had a hand in establishing the railroad boomtown during the race west to complete the Transcontinental Railroad, one small railroad thing they had no involvement in was the Cheyenne Electric Railway Co, or CERCo. Never heard of it? Well neither did I until this morning, but here's a basic rundown after the break.

By 1887, Cheyenne's Union Pacific Depot was built opposite the Wyoming State Capitol and it brought both city pride and movement to its citizens, which meant it was high time for a streetcar system. It is here that literature on when the establishment of the Cheyenne Street Railway (CSR) and which companies comprised it differ. What can be agreed on is that the CSR was first organized in 1886, before Wyoming's statehood, and by 1887 it had merged with another company and received its permit to lay track.

From here, operational information on the CERCo. is slim, but in the period of electric railway oprations, the company appealed to the Wyoming Judge Advocate General in 1918 asking for a decrease in fares for both enlisted and civilian personnel around Fort D.A. Russell (reduced to 7 cents). The JAG agreed to honor the contract modification as it would "eliminate much inconvenience and cause no appreciable hardship," on the condition that ticket offices be established at each end of the line to enforce this new fare.

-----

|

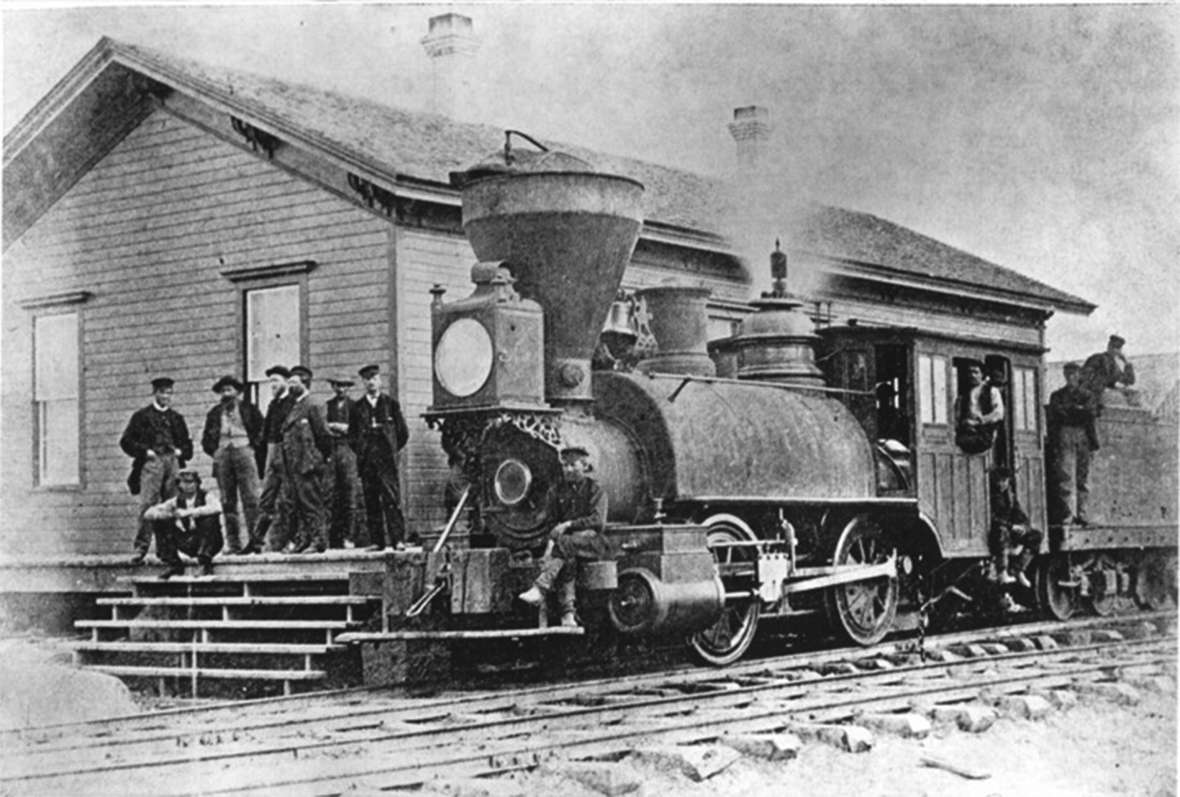

| The first Union Pacific engine in Cheyenne, 1867. (WyoHistory.org) |

Cheyenne was first established by the Union Pacific's surveying team on July 4, 1867 while on its Hell-on-Wheels bender towards Promontory Summit, with General Grenville M. Dodge receiving credit and naming the town after the local Cheyenne tribe. The UP would cross the Crow Creek, a tributary of the North Platte River, here and the town would be joined by Fort D.A. Russell three miles west. In November 1867, the UP's construction team would finally reach Cheyenne and skyrocket the population to well over 4,000, earning its nickname, "The Magic City of the Plains."

|

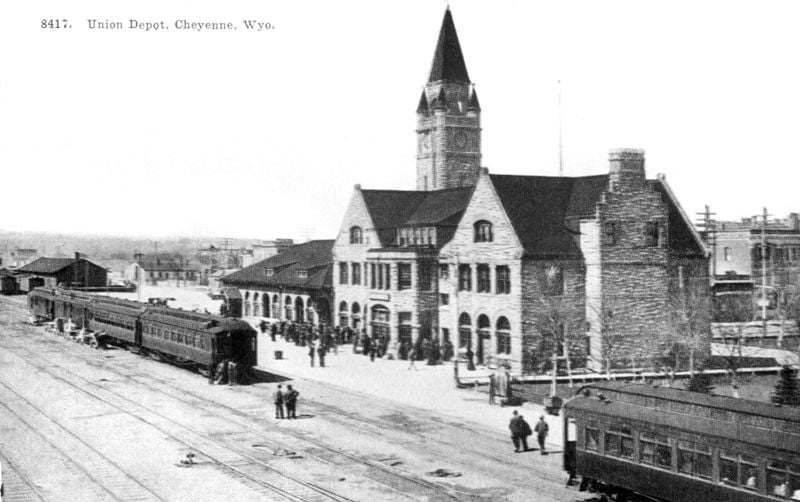

| Cheyenne's Union Pacific depot, 1909 (Wyoming Tribune Eagle) |

Usually, many cities would be excited at the prospect of a new trolley system, but not Cheyenne: citizens living along 17th St. raised complaints that trolley bells would cause too much noise pollution. Mayor Charles Riner decided to ignore these complaints, as one does. June 1887 saw the final routing plans of the CSR going from the UP depot, head north to the Cheyenne Fairgrounds via 16th, Eddy (now Pioneer), 22nd, O'Neil, 25th, Dillon Ave, and 27th St.

|

| Cheyenne in 1889, one of the rare shots of the Red Line horsecar heading fo the Fairgrounds (C.D. Kirkland) |

The next month, three brand new horse-cars would emerge from the Cheyenne Carriage Company. The contract originally called for four cars, with more from outside manufacturers. Unfortunately, several of the contracted companies had undergone massive fire damages, so when the system opened in January 1888, there was only one car for each of the three lines: Red Line to the fairgrounds, Yellow to Russell Ave, and Green from the Capitol to the Cemetary. By contemporary newspaper accounts, the horsecars were "very well built".

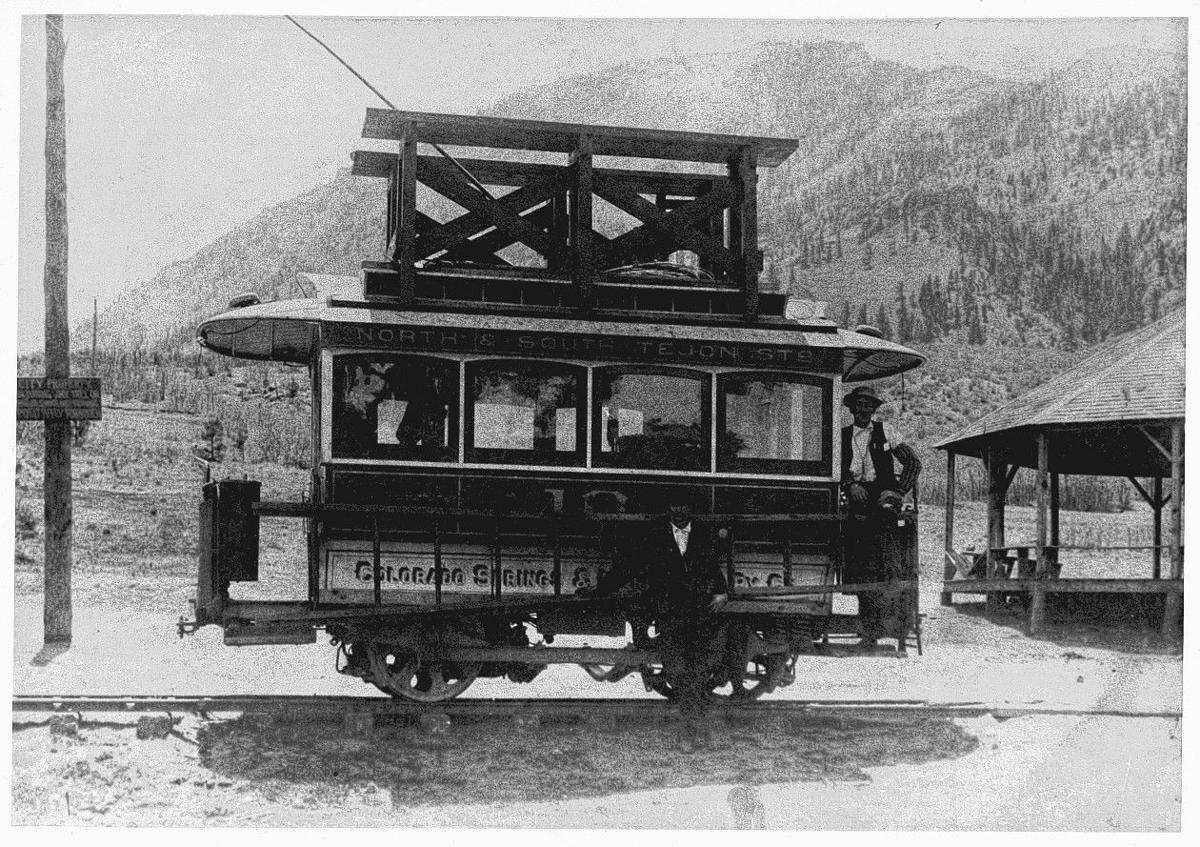

Ridership declined early for the horse-car line, and it quietly closed in August 4, 1892 after being deemed "unprofitable." After a gap of 14 years, the Cheyenne Electric Railway Company (CERCo.) was established by Thomas Cosgrove, president of the First National Bank of Cheyenne. With additional capital from prominent businessmen Francis E. Warren and Joseph M. Carey ($5000 each, which in 2019 dollars is $144,075), the new electric railway could now reach Fort D.A. Russell from 15th Street and Capitol Avenue in just 5.24 miles of track (the .24 being the carhouse at Cribbon Avenue). A nickel could get you anywhere in the city, but heading out to the Fort cost you a dime, and if you were under six, you could ride free with an adult.

|

| A Colorado Springs & Manitou Railway electrified horsecar, probably similar to what ran on the CERCo. (Pikes Peak Newspapers) |

|

| A postcar view of a CERCo Birney car with the Union Pacific depot in the background (Don Ross) |

The rolling stock of the CERCo. comprised of antique Brill cars from the same era as the Portland Council Crests. After WWI, the CERCo. would purchase a new fleet of Birney cars to ply the streets in 1922. These cars were light enough to run on the system's 52 lb rail, which even for street track was absolutely light. The system would go on for two more years before it was purchased privately in 1924 and converted to buses. The Birneys would be sold off to various railways, including the Fort Collins Municipal Railway, and regrettably the only trolley that still runs in the Magic City of the Plains is a tourist trolley bus. All that remains of the CERCo. is the original carbarn and an informative plaque.

|

| The CERCo's headstone, for all intents and purposes, showing two of the Brill cars. (Wyoming in Motion) |

-----

So that is the very very brief and often patchy history of the Cheyenne Electric Railway Co. If anyone does have anymore information about this boonie Birney system, please hit me up on my twitter account or get in touch with my Wyoming-based editor on his. You can also financially help us by buying a shirt (new designs incoming). Next week, we look at the Sheridan Interurban, but until then, ride safe and stay healthy!

Tuesday, March 17, 2020

Trolley Tuesday 3/17/20 - The Laramie Horsecar

Welcome back to a carhouse-quarantined Trolley Tuesday, which is still right on schedule, where today my editor Nakkune and I will be taking you through the state of Wyoming's public transit operations in a bit to fill up the remaining month since we've just about exhausted everything Arizona had to offer. Now I know we have the whole pandemic going around, but rest assured: in times of quite possible one of the biggest and most mysterious pandemics in recent memory, the best thing we can all do right now is be healthy, be hygienic, and most of all be level-headed. That way, we can all ensure our loved ones and ourselves are safe from the virus. In the meantime, allow yourself to be distracted as we start our journey in the Cowboy State with the Gem of the Plains: Laramie!

(All info contained and retold in here originally appeared in the Laramie Boomerang by Judy Knight, all rights reserved, no plagiarism intentional.)

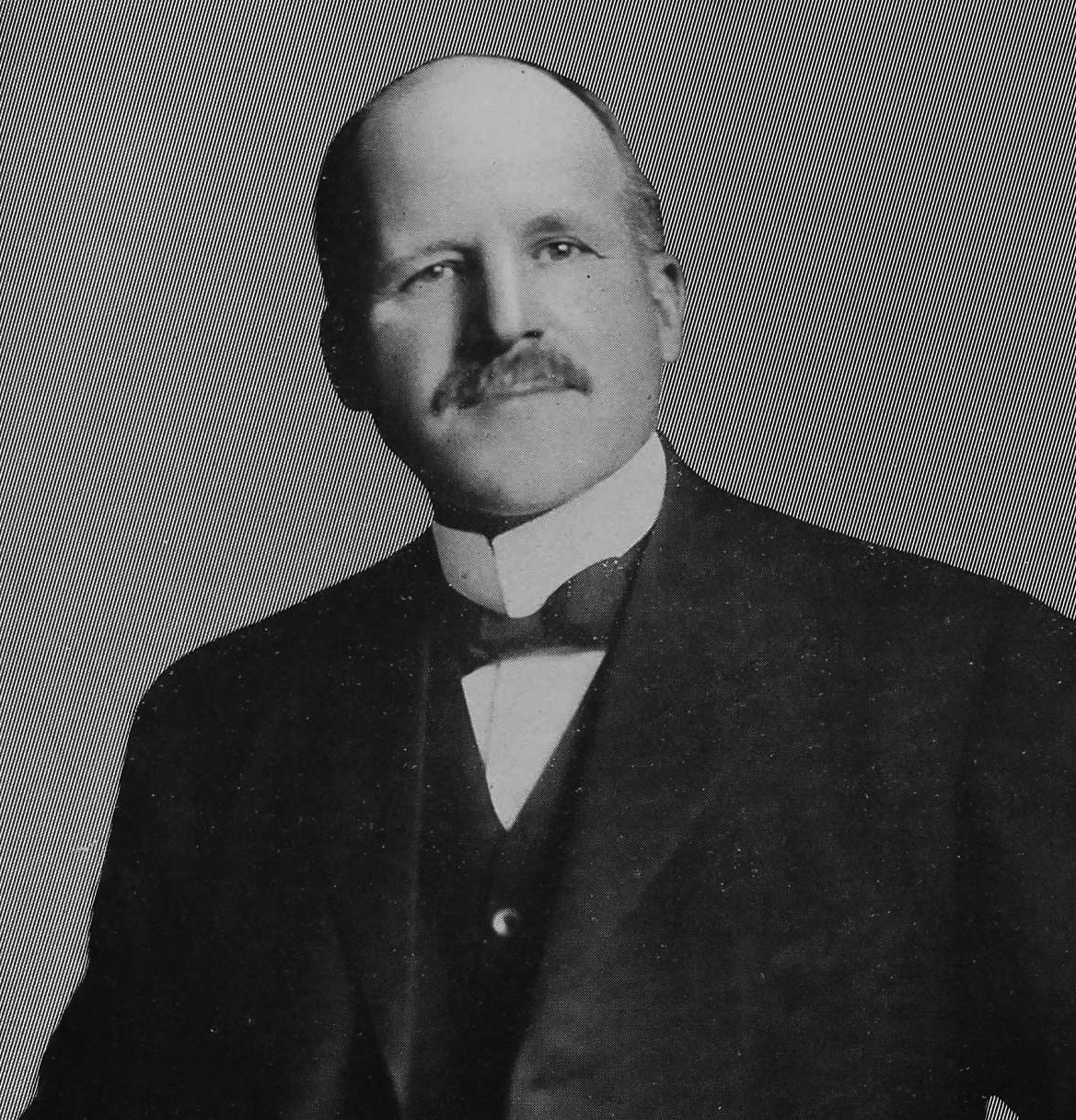

The first corporation to announce a proper street railway was organized in 1887 by James Vine, Hon. J.W. Blake, and then-mayor N.F. Spicer serving as the board of trustees. Unfortunately, this effort seemed to go nowhere and it wasn't until 1890 when the Laramie Improvement Company put advertisements in the Laramie Boomerang proclaiming new streetcars to their subdivisions in East Laramie in June 1890, emulating the popular streetcar suburban boom. Unfortunately, this went nowhere either and the town was itching for some decent public transit to make the town mobile. This is where Mr. Francis M. McHale enters the picture.

Not much is known about McHale's personal life, other than his birth in 1858 and various marriage certificates, birth certificates, and census data up to 1910. What is well known, however, is how this young gun showed up to Laramie in March 1891 and sent the entire town into a tizzy. At the time, McHale was a 33 year-old lawyer and officer employed under the Western Farm Mortgage Trust of Denver; he was also married with one daughter and another on the way, and was every bit the family man he displayed as himself.

McHale first arrived in Laramie with the intention of buying oil property in Albany County (of which Laramie is the county seat). He also had an interest in building a “$50,000 hotel at the corner of Second and Garfield” (close to the Laramie Railroad Depot) but nobody would sell him the land or the buildings occupying that spot. It seemed by this point, his big mouth got ahead of him and McHale grandly proclaimed he was developing a railroad going from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Pagosa Springs, Colorado, to increase lumber traffic through Laramie and promote the "healing nature of the Springs that 'could cure anything from hydrophobia to delirium tremens." Word of his grand promises reached the Laramie City Council and from there, McHale had them on a leash.

At the time, many contemporary street railways were switching to electrical power but electricity was hard to come by and expensive to install for many smaller towns, and Laramie was no exception. Despite the existence of an electrical plant in town, McHale drew up plans with local business owners August Trabing and James Vine to create a horse-drawn system using a corporation charter he gained from the state of Wyoming. McHale also stirred the local crowd, holding interviews and gaining support until he city council voted unanimously to grant the overeager businessman an exclusive franchise as the "Laramie Tramway Company", or LaTCo. $100,000 of capital over various stocks and bonds were raised and many skeptical councilors were left shocked this got though.

McHale promised the city council that eight miles of horse-drawn track would help satisfy public movement, with the choice of animal power a consequence of a ban on steam-powered trains through neighborhoods. The city council found this agreement worthy to honor, and lightly warned McHale that if four miles were not laid by the same date, 1892, the franchise would be forfeited. This deal lasted until August of that year, when McHale returned to Laramie saying that his "Denver directors" had had an epiphany and desired an electric system instead. (Suspiciously, none of his cohorts nor any Laramie-based LaTCo officers were consulted.)

The Union Pacific was briefly swindled into the deal, as McHale wanted to purchase 24-lb rail from their Laramie rolling mill rather than the 16-lb rail commonly used by any normal horseline. All through the fall and winter, McHale and his friends continued to try to drum up financial support for the line while track construction languished. Suspiciously, what little construction the Boomerang could detail was documented 50 years later, wherein "one streetcar company was using cover of darkness to tear up track laid by a competing company."

1892 brought with it a landslide of trouble, starting when McHale's employers, the Western Farm Mortgage Trust Co, was thrust into recievership due to a drop in wheat prices and ill-timed farm expansions that left many Colorado farmers unable to pay their mortgage, bankrupting the trust. The trouble continued that summer of June 1892, when all the Albany County properties McHale bought or traded for were put at auction by legal action from G.W. Griffith, one of McHale's former friends and a representative of LaTCo in the East.

Realizing they were all effed, and with the franchise about to expire, Griffith, Trabing and Thomas all pleaded the city council to extend the franchise and change the name to the "Laramie Electric Tramway and Light Company." (along with wanting exclusive rights to mount electric lights in Laramie) The trio did this to at least save the money they had invested into McHale's grandiose scheme. The city council took pity and granted the amended franchise, with the Boomerang suspiciously reporting, "Mr. F.M. McHale, originally president of the company is now not connected and is living in Kansas." This was the last time any talk of a trolley appeared in Laramie, which continued into the 20th Century without a single mile of track ever laid.

So what happened next? Both August Trabing and James Vine, original investors in LaTCo, ended up becoming mayors of Laramie later on, while both the Colorado farmers and Eastern investors who funneled their money into McHale's schemes all lost their entire investments through the failure of Western Farm. As for McHale, he and his family was found to be living in Hoisington, Kansas in 1895, then moved to Lawrence, Kansas, by 1900. By 1910, the trail went cold as census records revealed McHale was living in Knoxville, Tennessee. Thus ends the odd, swindling saga of Mr. McHale's horsecar scheme.

(All info contained and retold in here originally appeared in the Laramie Boomerang by Judy Knight, all rights reserved, no plagiarism intentional.)

----

|

| Laramie, WY, circa 1888. Good doggy. (Old Town Laramie) |

In the 1890s, Laramie, WY was the epicenter of several regional railroads and industries serving not just cattle and meat packing, but also rolling mills, railroad tie treatment, breweries, glass manufacturing, and electric provisions. The University of Wyoming was also established not long before, with an agricultural college added by the turn of the decade. Laramie was also mighty progressive, as several women were able to cast votes and serve on juries long before the Seneca Falls Convention under the first Wyoming Territory legislature. To satisfy the growing modernism of what was once one of the most lawless towns in the territory, it was high time for that great tool of modernism to make its debut: the horsecar.

|

| A horsecar of the Market Street Railway, circa 1880s (SFMSR Archives) |

|

| An image of Francis M. McHale, if we could find one. (Who knows?) |

|

| An early converted horsecar running on electric wires, under the Milwaukee Electric and Light Co, 1890 (We Energies) |

McHale promised the city council that eight miles of horse-drawn track would help satisfy public movement, with the choice of animal power a consequence of a ban on steam-powered trains through neighborhoods. The city council found this agreement worthy to honor, and lightly warned McHale that if four miles were not laid by the same date, 1892, the franchise would be forfeited. This deal lasted until August of that year, when McHale returned to Laramie saying that his "Denver directors" had had an epiphany and desired an electric system instead. (Suspiciously, none of his cohorts nor any Laramie-based LaTCo officers were consulted.)

|

| The "Huge Monster" of Laramie, where Union Pacific rail was rolled and ties were treated. (Albany County Historical Society) |

|

| A Western Farm Mortgage & Trust advertising flyer from Lawrence, Kansas, 1895. (Unknown Author) |

Realizing they were all effed, and with the franchise about to expire, Griffith, Trabing and Thomas all pleaded the city council to extend the franchise and change the name to the "Laramie Electric Tramway and Light Company." (along with wanting exclusive rights to mount electric lights in Laramie) The trio did this to at least save the money they had invested into McHale's grandiose scheme. The city council took pity and granted the amended franchise, with the Boomerang suspiciously reporting, "Mr. F.M. McHale, originally president of the company is now not connected and is living in Kansas." This was the last time any talk of a trolley appeared in Laramie, which continued into the 20th Century without a single mile of track ever laid.

|

| The much more developed Cheyenne Electric Railway, just before 1917 (Ranch Wife) |

|

| Laramie continues to be a vital outpost of the Union Pacific, with the town taking care of the old railroad depot and adjoining park. (Dieselpunks) |

-----

Thank you for reading today's hard swerve Trolley Tuesday. As always, you can find mine and my editor's Twitters in the links provided, you can also help support the history posts by buying a shirt. Despite the way we all have to isolate ourselves for the forseeable future, it is our hope your interest and attention are positively affected by our posts. Ride safe, ride healthy, and we'll see you on Thursday.

Thursday, March 12, 2020

Trolley Thursday 3/12/20 - Valley Metro Rail

A phoenix is a legendary bird that is said to expend itself by flashing into flames upon its death, then remake itself from its own ashes, ensuring that the bird is immortal and is a symbol for renewal and longevity. The city of Phoenix is much the same, as the original Phoenix Street Railway (PSR) was seriously affected by a large fire in 1947 and abandoned the year after, but in its ashes rose the Valley Metro Rail in 2008. On today's Trolley Thursday, we look at how the Valley Metro was able to spread its wings, and the struggles it has had in its current 12 years of operation.

Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa were to be connected by the new technically-interurban light rail line, which closely followed an original PSR plan drawn up to expand out to Mesa via Tempe in the early 1910s. Nothing came of this plan due to various reasons, but in 2005, ground was broken that would finally bring this early concept to life. The twenty mile stretch went from West Montebello Avenue in North Central Phoenix, then cut east at Washington and Jefferson Streets before winding into Tempe and ending at Sycamore in Mesa, with twenty eight stations in all designed to reflect their surroundings and blend in better.

The system would be rated at 750 volts on the overhead cantenary, and the maximum speed for the interurban would be 58 miles per hour. These cars would have to complete the 20 miles in just under an hour, which was pretty clippy timing given there were 28 individual stations. Just before the line's inauguration, the Valley Metro celebrated PSR 116's birthday, as she she had turned 80 on Christmas Day 2008 and the line's opening was planned for the next day.

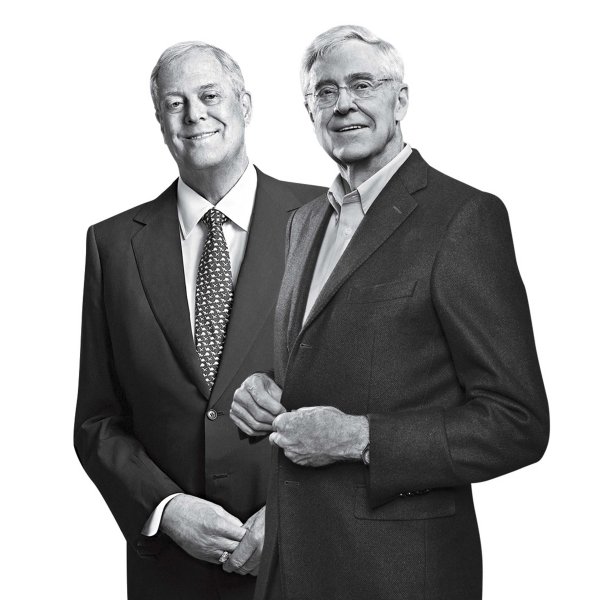

Regrettably, Phoenix's light rail was not without its enemies: enter grassroots group "4 Lane or No Train", which came into the public eye in 2018 opposing system expansions that would have met the city's planned expansion in 2034 to 66 miles total. Proposition 105 called for a rejection of a central reservation to be built on Central Avenue with six miles of the street being whittled to two-lane traffic. 4 Lane argued that this would "restrict business accessibility", which many small businesses in Phoenix gravitated towards. Further, the cost of the expansion was highlighted as a major threat, which is usually what ends up killing projects like this. (Light rail is a long term investment, after all) However, 4 Lane's "grassroots" efforts were actually being funded by two of the most infamous names in public transit since National City Lines: The Koch Brothers.

The brothers need no introduction: Charles and David Koch are (and were, in David's case) a pair of libertarian-conservative brothers who got their money through oil, so like the Streetcar Conspiracy before them, they had a vested interest in promoting bus lines over light rail. In honing in on the increase of sales taxes for citizens and warning about the loss of possible business, the Kochs were able to stem light rail growth in Little Rock, southeast Michigan, central Utah, and Tennessee to name a few through various puppet "grassroots" groups and think tanks to drive home their agenda. Following David Koch's (the social one) death on August 23, 2019, Phoenix voters rejected Proposition 105 in a landslide 116,190 to 69,662 just four days later.

In the leadup to the landmark vote, new extensions at 50th Street's infill station and Gilbert Road in Mesa helped make the Phoenix system more robust. The Northwest Phase 1 (an original Transit 2000 plan now pushed back... let's say a lot) and South Central extension from the downtown Phoenix hub both started construction in late 2019, with the Northwest Phase 1 (reaching north into the city) expecting to open by... 2023 (we hope). Future extensions include the Tempe streetcar in 2021, the Northwest Phase II (reaching the western parts of Phoenix) by 2023, and the Capitol/I-10 West extension in two phases (2023, 2030). ASU West, Tempe, Mesa, and Chandler are all being researched for possible extensions, proving the system has the capabilities to keep on expanding.

-----

|

| A 1999 Valley Metro Bus wearing the 1993-2006 paint scheme. (Msr69er) |

The current Valley Metro Rail began with the "Transit 2000 Regional Plan", or "Transit 2000", introduced in... the year 2000. Through a .5% sales tax, Phoenix voters aimed to improved the bus service and create a light rail service for better transportation at an affordable budget. The plan wasn't new, having been first proposed in 1989 as the "ValTrans" elevated rail system, but it was turned down by voters due to "cost and feasibility concerns." The initial plan called for $1.4 billion across twenty miles in construction costs, with a further $184 million in operational costs once the system was running, but it showed promise.

|

| Valley Metro Rail's original route, prior to extensions. (The Transport Politic) |

The trains would run similar to the Metro Blue and Gold Lines and other modern streetrunning installations: a raised "center reservation" down the middle of the street, with small private right-of-ways found at bridges. A minor hiccup occurred during construction when significant stretches of rail were found to have cracks due to improper plasma cutting with the fault landing square at the construction contractor's doorstep. The cracks were found in March of 2008, but repaired by May at a cost of $600,000 (not footed by the contractor). Despite this, the last of the concrete and rail were laid anyway in April and the first 50 light rail cars from Kinki Sharyo arrived for testing.

/3143531456_27ae85732d_b-5c48e6b44cedfd000137230f-04e646bde4694e2dbfac6ab4b31749f0.jpg) |

| A Valley metro Kinki Sharyo LRV departs Smith-Martin/Apache, one of many median stations on the line (Steven Vance) |

|

| Phoenix Street Railway No. 116 sits on the sidelines during the Valley Metro's opening festivities, having recently turned 80 (Ixnayonthetimmay) |

The initial ridership proved a success, and it just kept rising and rising as the initial 44% farebox recovery was soon surpassed as the enormous ridership brought in plenty of revenue to offset the operation costs by $44 million by 2014. Urban development was also fostered in downtown Phoenix and Tempe, which gave the Valley Metro more incentive to grow. The first extension stretched into Central Mesa, costing $200 million over 3.1 miles and adding 5,000 daily riders to the fareboxes in its four new stations.

|

| A local business, the El Fenix panderia, supporting 4 Lanes or No Train, in South Phoenix (Associated Press |

|

| David (left) and Charles Koch (right), anti-rail billionaires behind the new Streetcar Conspiracy. I made the picture deliberately small. (TIME Magazine) |

|

| The first Valley Metro tain arrives at the new 50th Street station, and it's not in service. Great. (Gannett Fleming) |

In the meantime, ridership and travel times remain relatively reasonable, with the entire route taking 83 minutes from Phoenix to Mesa. The system also boasts one of the highest ridership compliances in the country, at 94%, with no foreseeable decline in ridership right now. Though the system remains a single line (much smaller than the PSR), it has certainly proved itself healthier and hardier than its predecessor, with the hopes it continues to be one of the best streetcars in America and a source of growth for Phoenix, Tempe, Mesa, and its surrounding neighborhoods.

|

| A recent study map from early 2019 showing the planned expansions of the Valley Metro Rail. (Downtown Mesa!) |

-----

Well, dear reader, I'm in a bit of a panic as is my editor. Unfortunately, Arizona doesn't have any other significant light rail or trolley systems to talk about beyond Phoenix and Tucson. However, fret not! As I write this by the seat of my pants, this month is also going to look at another state barren of its streetcars: Nakkune's home state of Wyoming! I'm sure we can find some way to fill time while this month is still young. In the meantime, follow our social medias, go buy a shirt if you want, and ride safe out there!

Tuesday, March 10, 2020

Trolley Tuesday 3/10/20 - Phoenix Street Railway

If you come to Los Angeles, you'll find the San Fernando valley is littered with references to a man named Sherman: West Hollywood's former town name was Sherman, the former Pacific Electric San Fernando line terminated at Sherman Oaks, and the current LA Metro Orange Line bus goes from Canoga Park to North Hollywood via Sherman Way. Who was this Sherman, and how did he affect not only Los Angeles, but Phoenix, Arizona, in the late 1800s? Find out about this, and more on Phoenix's very own streetcars, in today's Trolley Tuesday.

Two years prior to that, Sherman and Collins also established the original Phoenix Street Railway (PSR) in 1887 as (you guessed it) a real estate venture. As Phoenix was cut into various land subdivisions, Sherman determined the best way to promote landbuying was to give the citizens a way to move about. Electrification came quickly by 1893, and more than 3000 people welcomed the movement the trolleys provided.

Back in Phoenix, however, Sherman's trolley continued to grow. At the time of Sherman's retirement, the PSR had opened the first interurban line to Glendale, with others planned to reach Tempe, Mesa, and Scottsdale and also totally electrified the entire system by 1909. A competitor had also appeared, the Salt River Valley Electric Railway, by 1912. They quickly hired an army of engineers to build lines to Mesa via Tempe and Scottsdale, but it was found that by 1914, nothing was constructed save for some digging on Van Buren and Monroe Streets on the south side of town. The company was assumed abandoned by 1914.

-----

|

| Moses Sherman, 1853-1932 |

Moses Hazeltine Sherman was born on December 3rd, 1853 in Rupert, Vermont. His original goal was to be a teacher, but after obtaining his teaching certificate from the Oswego Normal School in New York, he cut his career short and moved to Prescott, Arizona. To finance his teaching career, he began brokering mines and ranches under the interested eye of Governor John C. Fremont. In no time at all, Sherman was appointed the State Superintendant of Public Instruction with the title of Adjutant-General of the Territory, serving two terms. Sherman would continue to use his "General" title after he stopped teaching completely, instead opting to go into the money business by founding the Valley Bank of Phoenix in 1884.

Spending time in the state capital helped Sherman grow fond of the area, which at the time was barely being established and settled as a non-mining town. The Southern Pacific railroad was the first to reach Phoenix in 1879 to serve commercial needs driven by canal and agriculture. The Arizona Industrial Exposition was held for the first time in 1884 to foster good will and camraderie amongst inhabitants of the then-Arizona Territory, and continues up to today with the Arizona State Fair. Phoenix's capitol site was founded in 1889 when Moses Sherman, with associate M.E. Collins, donated 10 acres of land once the town was determined to be the new center of the territory.

| Horsecars lined up outside the old County Courthouse, 1890s (Rogue Columnist) |

Moses would not stay around to see the growth he planted, as he would move to Los Angeles in 1890 to establish the Los Angeles Consolidated Electric Railway with Eli P. Clark, his brother-in-law. This system would become the Los Angeles Pacific's "Balloon Route" between Venice/Santa Monica and Downtown LA via Hollywood and Venice Blvd. The system helped Los Angeles escaped its economic slump at the time, and would eventually merge with the Southern Pacific in 1906, with the system's owner, E.H. Harriman, earning a cool $6 million from Sherman. The General would retire shortly after in 1911.

|

| Los Angeles & Pacific car "Hermosa" on an excursion on Sherman's Balloon Route (KCET) |

|

| The street railway map by 1909, with connection to the ATSF and Arizona Eastern (Mike McDearmon) |

The competitive period also brought a severe strike on the streetcars, with motormen and conductors up in arms against the management's laissez-faire upkeep of the system in 1913. With anti-union citizens boycotting the strike and the creation of the Salt River Electric Railway cutting into their profits, the PSR was in dire straits. Despite it all, the PSR continued to expand until it finally reached its maximum growth in the 1920s through several line extensions: 33.6 miles over six lines with powerlines delivering an interesting 550V-DC to its heritage fleet of wooden ex-horsecars and San Franciscan-patterened street and interurban cars.

| One of the PSR's early "California Car" type streetcars, 1920s (Rogue Columnist) |

By 1925, the public had had enough and urged the city council to buy the system as a means of improving it. Upon purchase, the city of Phoenix implemented increased arrival and departure frequencies and better maintenance to the relief of many, and brand new trolley cars just in time for Christmas, 1928. These cars, built by the American Car Company as "Double Birneys", remained the workhorses of the PSR fleet for the system's remaining years, where it was remembered fondly by locals along with the slogan, "Ride a Mile and Smile."

Unlike many street railways, Phoenix's system did not simply die by bus; instead, it died by fire. On October 3, 1947, a massive fire swept through the city that also burned down a carhouse that contained almost the entire fleet of PSR's double Birneys. In February of next year, Phoenix officials declined rebuilding the streetcar service and abandoned service, switching transportation plans to center around bus service and automobile traffic.

The only remaining pieces of the PSR reside in the Phoenix Trolley Museum on 1117 Grand Avenue. Double Birney No. 116 was preserved following closure and restored to as-delivered condition as a static-display inside its small shed. Public transit in Phoenix is now served by the Valley Metro light rail system, which covers one of the planned interurban routes out to Tempe and Mesa, but more on that later...

| Double Birney 517 turns on the corner of Washington and 2nd, 1940 (Rogue Columnist) |

| The final iteration of the Phoenix Street Railway lines at closure. (Rogue Columnist) |

The only remaining pieces of the PSR reside in the Phoenix Trolley Museum on 1117 Grand Avenue. Double Birney No. 116 was preserved following closure and restored to as-delivered condition as a static-display inside its small shed. Public transit in Phoenix is now served by the Valley Metro light rail system, which covers one of the planned interurban routes out to Tempe and Mesa, but more on that later...

|

| The Phoenix Trolley Museum's old location at Hence Park, with Birney 116 (John Samora, AZ Central) |

-----

So that brings Phoenix's original trolley system to a close! If you want to support the Phoenix Trolley Museum, please visit their website or follow their social media wherever highlighted. And, as always, I sell tee-shirts if you want to see one of my drawings pasted across your torsos, and be sure to follow me and my editor on social medias if you want more content. Next week, we look at the modern Valley Metro and how it's doing. Until then, ride safe!

Thursday, March 5, 2020

Trolley Thursday 3/5/20 - The Old Pueblo Trolley

Tucson went without a streetcar service for over fifty years after the original company, Tucson Rapid Transit, went under in 1930. In that time, buses quickly took over as man are wont to do, but that didn't mean the trolley would be gone forever. A clever woman named Ruth Cross would be the catalyst for Tucson's trolley revolution, which began with a tiny trolley car from California.

1983 brought several important events in Arizona history: The NCAA Fiesta Bowl between the ASU Sun Devils and University of Oklahoma Sooners saw ASU cruise to victory, the Phelps-Dodge Corporation feuded with copper miners and mill workers over layoffs and wage cuts due to a declining mining operation, and tropical storm Octave became the worst cyclone in state history with over $500 million in damages. But at the University of Arizona, something small but just as important was cooking.

In the time since service suspension, the city of Tucson helped the OPT move into a former cabinet shop as their new carhouse in 2014. Currently, the OPT runs historic bus excursions using the aformentioned Bisbee Lines No. 8 (itself a native of Arizona) but hopes to one day continue operations by sharing tracks with the Tucson sunlink. Only time will tell if their poles are raised once again.

-----

|

| Two men inspect the damage left by tropical storm Octave, 1983 (Arizona Daily Star) |

|

| The main gates at ASU Tucson, present day) (Real Tucson) |

The university's centennial was coming up in 1985, and to really ring in the big "100" with a bang, Centennial Celebration director Ruth Cross wanted to bring back an honored Tucson institution in time for the festivities. In 1983, she formed the Old Pueblo Trolley (OPT) non-profit to raise funds and coordinate with the city as well as to call on volunteers and equipment to eventually run the railway. Over the next two years, a one-mile stretch of track was recovered from the original Tucson Rapid Transit (TRT) from 5th and Broadway to the main University gate at Tyndall Street. The OPT also has the rare distinction of most its alignment being original street track dug up from the road, rather than being relaid or realigned.

To obtain a streetcar, the OPT turned to the Orange Empire Trolley Museum (OERM) in Perris, California, desiring something small and easy to operate. The OERM chose to lease ex-Pacific Electric Birney No. 332 to the fledgling operation for ten years, on the condition that the OPT restore the car to running order.

|

| ex-Pacific Electric 332, as Tucson Rapid Transit 10, paused at the Alpine/Broadway platform at the OERM (Myself) |

Car 332 was originally built by Brill in 1918 for operation on the "boonie" lines in Pasadena, San Bernardino and Redlands, and retired from service in 1940. Following retirement, MGM purchased it and surviving sister 331 for use in films like Comrade X (1940) and, famously, Singing in the Rain (doubling for sister 337, which was sliced in half for interior shots). Following their film service, the cars were purchased by the Southern California Electric Railway Association (SC-ERA) and preserved in Perris, CA. The car would take over six years of hard work to restore out of that ten-year lease but it would first operate on OPT charter and member runs in 1991 as TRT No. 10.

|

| Gene Kelly leaps off PE Birney 332's (or 331) roof to land safely in Debbie Reynold's car in "Singin' In the Rain". (MGM Studios) |

|

| Ex-Hankai 225 operates on the OPT University Avenue stretch. (Jack Garcia) |

The next year, OPT would purchase ex-Hankai Tramway 255 from Osaka, Japan. This car was significantly younger, built in 1953 as Japanese City Lines 869. Upon retirement in 1992, OPT snatched it up and kept its Hankai Tramway identity. Due to the 869's pantograph and the 332/10's trolley pole, the overhead wire had to be configured primarily for trolley pole use (necessitating staggered and curved wire on corners). Volunteers from the Tucson Electric Power company helped put up the wires.

Public service began in 1993, way past the original centennial celebration, but it was still a cause to celebrate for Tucson: the town had its trolley back. In 1995, Car No. 10 returned to the OERM as the museum did not want to extend its lease, but the car continues to wear the green and cream of the Tucson Rapid Transit as a tribute to the little railway that helped it live again. A nine month period around the same time saw JCL 869 returned to service under its original number and roadname.

|

| Ex-Brussells 1511 leads JCL 869 down an unknown Tucson street, 2009 (Ed Haven) |

Two more cars would join the fleet: ex-Brussells No. 1511 to replace 332 as the two-axle car, and a Toronto PCC. The Brussells car arrived in April of 1995 from Phoenix, AZ, after a plan to use it as a restaurant went belly-up. Toronto PCC 4608 reached Tucson in June, the next year, and would be gauged down from the weird Toronto-only gauge of 4 feet, 10 7/8 inches. The initial alignment operated until 2009, when an extension and loop was built at 5th avenue via the 4th avenue Underpass. This gave the OPT the ability to meet Amtrak trains and gain more foot traffic for both tourists and locals in the city. Old Pueblo also invested in a large historic bus collection, one of which (Bisbee Lines No. 8 from 1938) was operable by 2018.

|

| The new Tucson sunlink at ASU's main gate on Park Ave. (Visit Tucson) |

However, trouble was soon brewing. In 2006, the "Sun Link" light rail program was begun after 60% of voters approved of the "Regional Transporation Plan". Much of OPT's single track alignments were now double-tracked across almost its whole route and a new maintenance facility would be constructed close to what is now the OPT's new carbarn. This meant that in 2011, the OPT's poles would go down under a suspension of service.

In the time since service suspension, the city of Tucson helped the OPT move into a former cabinet shop as their new carhouse in 2014. Currently, the OPT runs historic bus excursions using the aformentioned Bisbee Lines No. 8 (itself a native of Arizona) but hopes to one day continue operations by sharing tracks with the Tucson sunlink. Only time will tell if their poles are raised once again.

|

| Old Pueblo Trolley's only operating piece of equipment right now: a 1938 White Coach Model 1204 for Warren Bisbee Bus Line, Arizona |

-----

Thank you for reading today's Trolley Thursday post! If you would like to find out more about the OPT beyond my hackneyed summary of their history, please visit their Facebook page, also follow the Tucson Historic Depot for more information, and as always: donations to them always help get them back on their wheels. As for me, all I can peddle is my Redbubble store if you want my doodles on your bodies. Until next time, ride safe!

Tuesday, March 3, 2020

Trolley Tuesday 3/3/20 - Tucson's First Trolleys

New month, new topics! From the chilly cloudiness of the Pacific Northwest, we descend into the hot, sunbaked deserts of Arizona! This month will focus on Tucson and Phoenix's transit systems as well as modern operations like the Old Pueblo Streetcar. As usual, this is all new territory for me, so I definitely hope you all enjoy what you're reading! For today's Trolley Tuesday, we look at how Tucson's trolley system first started.

-----

|

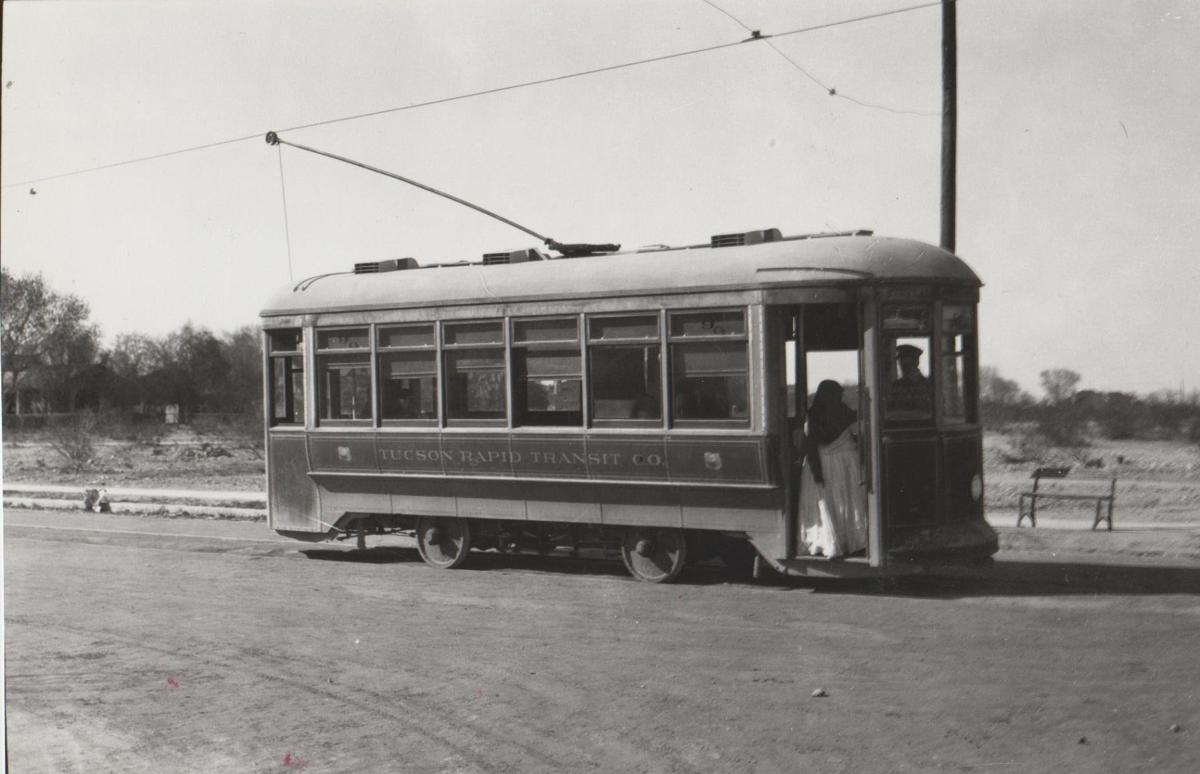

| (Jeff Wallace) |

1879 brought with it many important events in America: The Transcontinental Railroad had its completion date legally defined, Thomas Edison first demonstrated his incandescent bulbs at Menlo Park, New York's Gilmore Gardens was renamed Madison Square Garden, and the town of Deadwood, South Dakota, burned down with over $3 million in damages. But amongst all the events, a smaller revolution came to the town of Tucson, Arizona: its first trolley line.

|

| Horsecar No. 6, sometime after 1900 (University of Arizona) |

Entrepnuer Bill Morgan established a "herdic" service in Tucson two years after the town was incorportated. At the start of the decade, the town gained a connection to the West Coast via the San Diego-Tucson telegraph in 1873, but now it had a public transport service. A "herdic" is another word for a "horsecar", being a closed-body carraige on rails. It ran from Downtown to the Nine Mile Water Hole along the Canada de Oro wash. The herdic would be rerouted once in its two decade of operation: when the Southern Pacific arrived in Tucson, the tracks were moved to add a stop at the new train station.

|

| A headline in the Arizona Daily Star announcing the rebuilding of an original Elysian Grove building in 1924 (Arizona Daily Star) |

In 1898, the Tucson Street Railway (TSR) was established as a mule-drawn street railway. As the town was originally a stagecoach station, it never had any viable commodities to allow for electric streetcar service in a time when almost every electric railway in America was being established. This was also well before any main street in Tucson was paved, which meant pedestrians would often be bogged down in mud or trip over the raised steel rails. Nevertheless, the company managed to ring in the new century with an expansion north and south and even establish their own trolley park called "Elysian Grove."

|

| "The last of the Mule Trolley - Tucson 1906" (University of Arizona) |

By 1904, the TSR had more than eight miles of horsecar track, seven horsecars, and 34 head of livestock in both mules and horses. Unfortunately, the large amount of animals also meant frequent, if not inherent, scheduling issues as streetcar frequencies would always depend on how the animals were feeling that day. The city eventually had enough and, in 1906, forced the TSR to modernise with electric streetcars on heavier rail and running on overhead wire. The company was renamed the Tucson Rapid Transit Company (TRT).

The streetcar proved to be a welcome addition to the town, where car travel was otherwise foreign. In 1915, Tucson had gained a significant chunk of paved road and yet the TRT proved so successful the roster swelled to nine streetcars. Ten years on, three more streetcars were delivered to bring the grand total to twelve, and buses were brought in to supplement service with a consistent 15-minute service interval. Despite the size of the system, it never suffered any heavy line closures or other operational malady that plagued street railways three times its size around the US and continued to trundle along without fanfare until 1930.

|

| One of the TRT's tiny not-Birneys collecting a passenger. Adorable, isn't it? (Arizona Daily Star) |

That year, the Tucson City Council decided to discontinue streetcar service effective at the end of the year. On December 31, 1930, the last streetcar would roll along Tucson's streets before being shuttered and the tracks were paved over in favor of bus service. As quietly as it began, the Tucson Rapid Transit Company went as quietly for the next fifty years... until 1983, but that's a story for another time. (Shoutout to CGP Grey)

-----

Thank you for starting this new month of Trolleyposting with me, your motorman writer, and Nakkune, my editor. If you would like to financially support this series, please check out my Redbubble store where you can purchase merch made by me and keep this series going. As always, ride safe!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)