-----

|

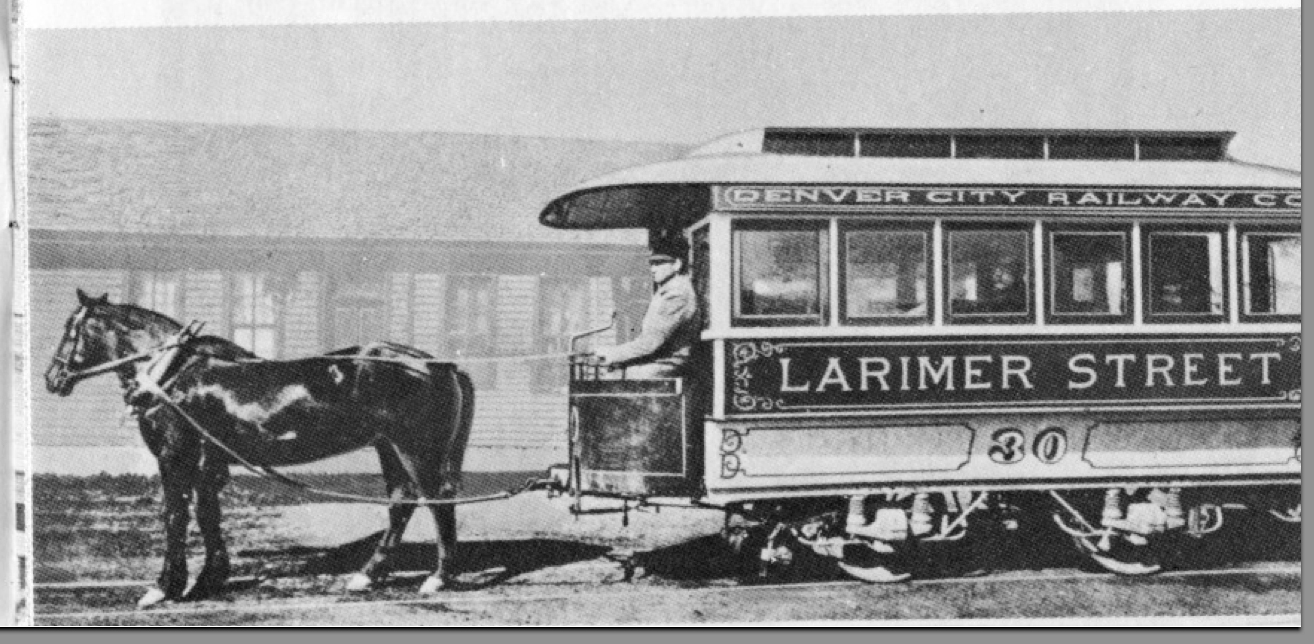

| A Denver City Railway Co. horsecar serving Larimer Street, 1871 (Posner Center) |

The first streetcar system to run in Denver was, appropriately, powered by ponies. The Denver Horse Railroad Company was formed in 1867 with an incredible thirty-five year city charter stating "the sole and exclusive right and privilege of construction of a horse railroad in the city of Denver and additions thereto." The first of these lines opened on December 17, 1871 connecting Seventh/Larimer with the Five Points neighborhood (one of eventually 78 neighborhoods altogether). By the end of the 1870s, the small system (eight miles) employed eighteen men, thirty-two horses, and twelve horsecars, necessitating a change in name to the Denver City Railway Company (DCR).

The new name-change not only brought heavier steel rail to upgrade the right-of-way, but it also brought along a period of fierce competition. As Denver was expanding, many land speculators saw the streetcar as a means to sell more land and up the value on their real estate, but the Denver City Railway served nowhere near their areas. The Denver Electric & Cable Railway (DECR) was launched in 1885 to compete with the horses on a fifty-year incorporation, but this panic scheme also had a major problem: what if electricity or cable was unprofitable? DCR had the exclusive right to horsecars, so some investors spun off into ANOTHER company (The Denver Railway Association, DRA) to gain the use of horses. This plan ended up offending everyone so much that the DRA reincorporated and renamed itself Denver Tramway by 1886.

|

| London Tram track featuring the underground electric conduit, beats overhead wires for some systems. (Dewi's Trains, Trams, and Trolleys) |

|

| A Denver Tramway cable car in 1895, one of the last cable cars due to electification. (Raton W.A. White) |

The economic panic of 1893 gave Denver Tramway a chance to finally boot its competition, Denver City Cable, after the latter went into receivership. Now politically intertwined, the Tramway urged the city council to "grant itself a franchise [the DCR] couldn't compete with", thus ensuring a guaranteed merger. Does this sound absolutely wrong? Yes, this is the kind of thing President Theodore Roosevelt would bust a trust over, because for all legal purposes, Denver Tramway now had a monopoly on public transit, with company stock bragging that the franchise was "without limit to time and therefore perpetual."

|

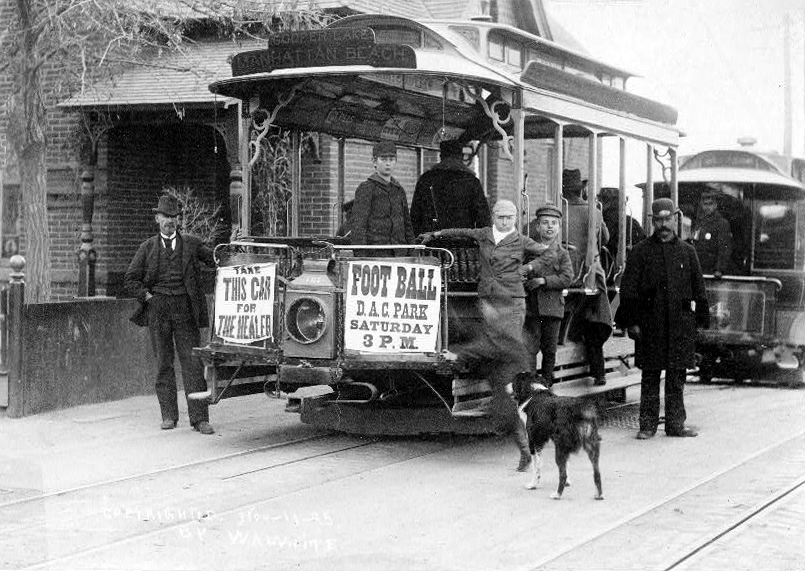

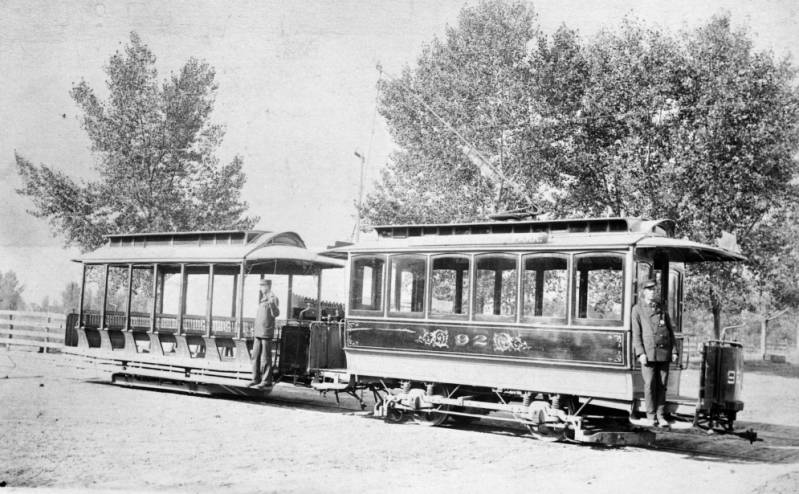

| A modernized horsecar with new trolley pole and trailer posed at Five Point-Whittier, 1890s. (Denver Public Library) |

|

| Thomas S. McMurry, looking unnaturally smooth (Denver Public Library) |

You'd think this would be the time where a lone politician would stand up and bring down the mighty monopoly in a grand and noble public gesture, and you'd be kind of right. Up until now (1895), Denver Tramway had a set share of profits going back to the city of Denver, but as the coffers filled and ridership increased, citizens felt like Denver Tramway wasn't putting enough back. Enter Thomas S. McMurry, a mayoral candidate who called for seperation of transit and government and for Denver Tramway to pay their fair share. When the transit company attempted to bribe McMurry as a peace offering pending his reelection, McMurry refused and immediately lost the 1899 election to a transit-friendly patsy named Henry V. Johnson. After this, Denver Tramway was able to keep any of the profits they earned.

The 20th Century seemed good for the Denver Tramway: they were experiencing record profits, the mayor was in their personal pockets, and their monopoly went unchallenged by any startups. The only problem was the ridership was beginning to turn on them. In 1905, citizens demanded the company close shop at the end of their franchise, despite claims of "perpetuity." Denver Tramway responded with a new franchise written as a precaution in 1906 that still gave the company plenty of monetary leeway, including fare rates set at five cents ($0.25 in 2019 currency) and Denver Tramway footing the maintenance cost of all infrastructure and equipment.

|

| Denver Tramway's station at 15th between Arapahoe and Lawrence, note the lack of headlights. (Christine Wieczorek-Mullen) |

This agreement seemed to have worked as, by 1917, the Denver Tramway saw 62 million trips a year, but like any good streetcar system, the money was tanking into the red. The Tramway brass petitioned the Colorado Public Utilities Commission and managed to get a 2-cent fare increase, but were promptly sued by the City of Denver demanding the original franchise be honored and keep the 5-cent fare. Denver Tramway would respond to this by laying off whoever they could layoff and cutting the pay of the rest who stayed, leading into one of the bloodiest events in Denver's mass transit history: The Streetcar Strike of 1920.

|

| Denver Tramway Building, as it looks today. (Denver Urbanism) |

-----

Thank you for riding and reading today's Trolley Tuesday report! On Thursday, we take a close look at the Denver Streetcar Strike and the end of the Tramway in the 1970s before spending next week looking at the cars and operations of both the Tramway and sister company Denver & Interurban. Until then, follow me or my editor on twitter, buy a shirt to keep our stock options open, and of course ride safe!

No comments:

Post a Comment