Welcome to the last Trolley post of July! As is tradition now with our transit experts of the month, we delegate onto them a guest post to write and have them impart their knowledge directly onto you, the

unwilling captive and interested audience. For this month, our expert, Jonathan Lee, has written for you a concise history on the city of Milwaukee's interurban and streetcar operations. There's a lot to be said, but from us here at Twice Weekly Trolley History, thank you for reading our material, for giving us the biggest readership we've ever seen, and we hope you all stick around for more in the future. Mr. Lee, you have the floor!

(Also all photos today are credited to Joseph Canfield, author of "TM, The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company," unless otherwise noted. Find the book link in the epilogue.)

-----

|

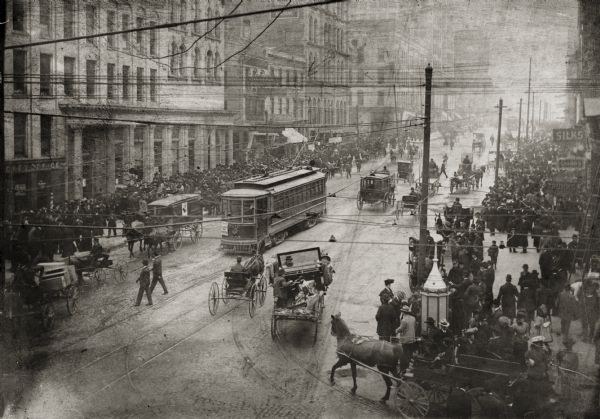

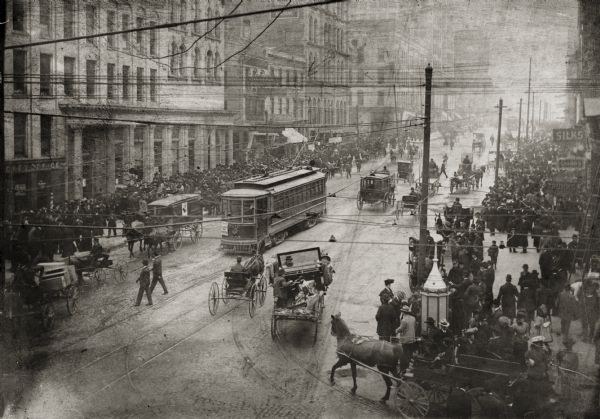

Just a normal day in at a Milwaukee intersection in 1900.

(Wisconsin History) |

Milwaukee means many things to many people: to Chicagoans, Milwaukee’s a cheap weekend getaway to a smaller version of their fair city behind the Cheddar Curtain, but to railroad enthusiasts, it’s synonymous with its hometown railroad: the once-transcontinental Chicago, Milwaukee, St Paul & Pacific- the Milwaukee Road for short. But to those who savor the finer things under wire, the city stood for one thing first and foremost - The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company (TMER&L), almost always known by its first two initials, “TM”- yes the “The” was always capitalized.

|

| The Milwaukee Electric's classic diamond logo. |

|

| An early TM city car. |

Milwaukee’s electric railways began with an outfit known as the North American Company, owned by Henry Villard (of the Northern Pacific Railway fame). The North American Company was perhaps the first electric utility holding companies. One of the keys to its growth was finding a market for daytime use of electricity. Early on, most power was used for illumination and only a few hours at night. All over the country, the emergence of electric street railways proved to be the perfect thing to fill this daytime gap in market demand, and the situation was no different in Milwaukee. Under his Edison Illuminating Company of Milwaukee, Villard purchased, consolidated, and electrified the various competing horsecar lines in the city, and induced local politicians and executives to invest in his interests.

|

Henry C. Paine. Postmaster,

transit investor, and stache master. |

One such person was Henry Clay Payne, a New England transplant who was the local Postmaster and investor in gas and street railway companies. He was a key figure in the union of the early city system into the Milwaukee Street Railway Company (MSR) in 1890. Payne's interests included the Milwaukee and Fox River Valley Railroad, which was planning an electric line from Appleton, Wisconsin to Milwaukee (this was never achieved, though other local interests eventually developed a disconnected system in that area that reached as far as Fond du Lac on the south end of Lake Winnebago). Appleton, along with Richmond, VA and South Bend, IN, was one of the first American cities to electrify its street railway system under the Wisconsin Light, Heat & Power Company, which was controlled by John I. Beggs. Henry Payne moved on to become Postmaster General under the first Roosevelt in 1902, leaving control of the MSR, in addition to the WLH&P, to John Beggs. Beggs' company included holdings in Racine and Kenosha, Wisconsin in addition to the aforementioned cities, and this is partly how the future TMER&L came to dominate the southeastern Wisconsin traction scene. Beggs was there on January 29th, 1896, when a court foreclosed on and sold the Milwaukee Street Railway, and on the same day, the TMER&L was incorporated to take over the MSR's assets.

|

John Beggs, transit holder

and handlebar boy for life. |

John Beggs felt that intercity electric lines (as the term “interurban” was in its infancy) were essential to connecting his scattered Wisconsin utility properties, and so he focused more on the their development and the city lines than their associated electric utilities, something which went on to haunt future management. However, this also meant that he was able to expand his system into one of the most expansive in the country, with connections as far from Milwaukee as Kenosha, Watertown, Burlington and East Troy. When the Chicago & Milwaukee Electric (predecessor to the North Shore Line) failed in 1908, Beggs attempted to take control of it and, had he succeeded, his system would have reached into Illinois and to Chicago. Unfortunately for him, Samuel Insull won out, and Kenosha was as far south as his empire ever reached.

One of John Beggs’ earliest competitors, and eventual acquisitions, was the Waukesha Beach Electric Railway (WBER). The WBER was chartered in 1894 to go between Waukesha to Oconomowoc, and construction was undertaken by the unfortunately named C.E. Loss & Co. of Chicago. (Fortunately, there were no losses incurred.) The line was extremely successful, in spite of not completely fulfilling its original charter; it only made it six miles north out of Waukesha, with its route beginning at the Chicago & North Western (C&NW) station in town. This shortfall was actually intentional, given the line’s eventual use as a pleasure beach railway. The promoters had hoped to develop a resort on Pewaukee Lake, naming it Waukesha Beach. This began as a bathing beach and idyllic country park, but soon became much more than that. A fleet of Pullman-built, 37-foot motor cars and similar, open-bench trailers hauled the masses to the beach, which quickly became a regional icon.

|

An early service to Waukesha Beach Yard, with the lake right at the edge of

the tracks. Note the interurban crew just sitting around. |

Eventually, as TM looked to expand west towards its original goal of Madison, the line from Waukesha to Pewaukee Lake began to look very attractive as a link in the new system, which it added in 1897. Unfortunately, the curves and grades out of Waukesha were not up to TM's exacting standards and were abandoned after the Watertown Division main line bypassed it in 1907. Over the years, this lakeside resort transformed from simple picnic grounds and swimming beach to one of the Midwest's most elaborate amusement parks. Billboards all over the region shouted “Waukesha Beach, the Fun Center of Southern Wisconsin”, including a roller coaster, multiple bandstands, baseball fields, and all kinds of rides and fairground-type amusements. TM built a short spur from the main line straight to the beach, with a storage yard to handle special trains, of which there were often a great deal, for the summertime crowds. A massive, castle-like substation was located at the junction for the beach spur, featuring a covered station and turning wye for the extra traffic.

|

The mighty 4-story Public Service Building in Downtown Milwaukee,

with an interurban service on the right and a city service just to the left. |

Beggs' ambition didn't solely translate into sheer distance and expanse, as he had grand designs for the system’s other aspects. In 1905, he completed the four-story Public Service Building in downtown Milwaukee between Michigan, Everett, 2nd, and 3rd Streets. This housed TM's corporate offices and served as Milwaukee's main interurban terminal. With two waiting rooms and 14 tracks, three outside the building and ten inside, it was the largest interurban terminal in the country at the time. Out in the country, sturdy waiting shelters were provided with distinctive architectural features, and in the major towns and terminal cities, storefront ticket offices and waiting areas were the norm until substantial off-street terminals were built by the 1920s. Interurban rights-of-way were built to a higher standard than most, with stone or concrete bridges, large fills and cuts, and generally broad curves to enable fast running and a smooth ride. This was best demonstrated on the line to Waukesha, Oconomowoc and Watertown, which passed through the rolling, sometimes rocky, sometimes marshy landscape of the southern Kettle Moraine. Electrification of the interurban lines was initially at 3300v AC, but although this had the advantage of allowing fewer substations per mile, its associated equipment was cumbersome and heavy, and the system was eventually converted to use 1200v DC, then finally 600v DC in 1927.

|

An early Milwaukee Electric interurban car, built by the

St. Louis Car Company. Note the fancy oval window. |

One area where Beggs' ambition did not extend, at least in terms of trackage actually built and operated, was north to Port Washington and Sheboygan. This was the domain of the Milwaukee Northern (MN), which has an independent history all its own. Detroit business interests, namely the Comstock Construction Company, built the Lake Shore Electric between Cleveland and Toledo, and the Rochester & Eastern Rapid Railway in upstate New York in 1899 and 1903 respectively. Their properties were built to high standards and the MN was no exception, with few steep grades, no sharp curves other than those in street trackage, and grade-separation from steam roads and major highways where possible.

The company went from incorporation (in October 1905) to initial completion (in November 1907) in a very short time, indicative of the boom years of interurban construction. Original plans called for 112 miles of line, with double track from Milwaukee to Cedarburg, where the line would split; one branch went north to Sheboygan, and the other northwest to West Bend and Fond du Lac. Some grading was done on the Fond du Lac branch, but it was never built. Nonetheless, the road's shops and a major station were located conveniently at Cedarburg. The “Northern” also built a downtown Milwaukee terminal at 5th & Wells, easy walking distance from the North Shore Line's station and reasonably close to TM's Public Service Building and used its own city line to get there following 6th Street. This street running was rather lengthy, and was be problematic in later years, but It was a boon from the start, with the Northern running an independent “city” service every 10 minutes. A suburban service from Milwaukee to Brown Deer was also operated for a time.

|

A Milwaukee Electric freight stops on the Beulah Siding

on the East Troy Branch, late 1960s. |

Unlike TM, the MN solicited freight service heavily and early, and established pick-up and delivery service for off-line customers at Sheboygan and Milwaukee like its competitor, North Shore. A street track connection was actually built between the Northern and the North Shore in Milwaukee, and the latter's Merchandise Dispatch cars ran all the way through to Sheboygan for a time, expediting goods such as plumbing fixtures from the Kohler plant nearby. This traffic was so ubiquitous that the trains earned the nickname “Bathtub Specials”. The close link between the MN and the North Shore can, in part, be explained by the fact that neither had anything to do with John Beggs' North American Company, and by the Northern's connection to another Insull property, the Wisconsin Power & Light's line from Sheboygan to Plymouth and Elkhart Lake. Insull eyed the MN to physically link his Wisconsin and Chicago-area holdings, but this never happened.

|

A map of the combined Milwaukee Electric and Milwaukee Northern lines between Kenosha, Sheboygan, Rancine, Beloit,

Lake Geneva, Madison, Fon Du Lac, and Milwaukee, mid-1920s. |

|

| An interurban right through a chair factory? Only in Milwaukee. |

Weakened by post World War I inflation and early auto competition, the MN was snatched up by the North American Company (NAC, probably the aircraft people) in 1922, with TM purchasing all of its outstanding stock. Operations were slowly integrated with those of TM, and eventually the old MN city and suburban services were cut. One of the new improvements was an off-street station in Sheboygan in 1925, and this served both TM and Wisconsin Power & Light cars. The MN express freights were continued, and some TM express motors were reconfigured to MU with those of the North Shore. Further improvements included a block signal system, upgraded ballast and roadbed, and rerouted track to eliminate some tight curves on the street in Port Washington. The latter’s end result that the main line punched through the main factory building of the Wisconsin Chair Company.

|

A "Duplex" articulated car on the "Rapid Transit Line"

crossing the Menomonee River and the Milwaukee Road. |

The other interurban lines also got some attention, with new, off-street terminals being built in Watertown, Burlington and Kenosha, the latter including a brand-new entrance into town on private right-of-way. During this period, TM became one of the very few interurbans to try offering dining service. An articulated car was built in Cold Spring Shops (more on that facility below) and outfitted with an all-electric kitchen and well-appointed dining area. It was first placed in service between Milwaukee and Watertown, but it was soon found that this route was not quite long enough for passengers to enjoy a full, proper meal, so it was moved to a Kenosha-Milwaukee-Watertown routing which took roughly two hours. However, since most passengers traveled to and from Milwaukee and not through it, the service was not economical and was dropped during the Depression, with the articulated car becoming an otherwise-standard interurban.

|

A contemporary advertisement from the 1920s advertising new

bus connections to Madison, WI. |

Other innovations of the time were not even rail borne. Bus connections were offered to places such as Madison, Fond du Lac and Lake Geneva, using what were then considered luxurious highway coaches. TM embraced buses as a way to expand, not replace, its interurban service, and eventually routes reached as far as Iron Mountain, in Michigan's Upper Peninsula! Another rubber-tired innovation was an early form of intermodal container haulage. The Cold Spring Shops forces worked their magic once again and came up with a box motor that could haul an intermodal truck trailer. This was quite successful for a time and helped make up for TM's early lack of freight service development and promotion. All of these improvements and modernizations did not go unnoticed by the nationwide transit industry, and TM was recognized for its achievements by receiving the Coffin Award for Innovation in Electric Traction in 1931, temporarily stealing it away from the three usually winning Insull-owned lines!

|

| The quite-interesting method of intermodal transportation pioneered by the TM, showing the compact container. |

|

Car No. 858 shows off some fashionable safety slogans as well

as a general cry for help. This car was originally built in 1911

by the St. Louis Car Company. |

Much of this took place under the gathering storm clouds of the Great Depression, and as its effects were felt by TMER&L employees, old wounds were reopened. Back in 1897, riots had erupted when motormen and other workers attempted to unionize and were met with scab labor. TM workers had long felt resentment at what they saw as the absentee ownership of the system by the North American Company, which was based in New York City. Local politics were trending left as they were across much of the nation, as people became rightly angry at the Wall Street bigwigs that had contributed to the economic suffering experienced by everyday people across the country. In 1934, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) attempted to get TM to recognize its union men and respect their demands. No progress was made, and the AFL called a strike early in the morning of June 26th, which initially went almost unnoticed. That same night however, union supporters, who were more frustrated with TM’s lack of action and were more action-inclined, stormed the Kinnickinnic car station and a group of streetcars outside of it, tying up traffic. Eventually, groups of unrelated agitators joined the fray (mostly jobless workers from other industries and parts of the city) who took out their unemployed frustration on the city's transportation provider.

|

The aftermath of the 1934 Milwaukee Streetcar Strike, showing damage

to car No. 624 and general fighting outside the Kinnickinnic Station. |

The result was dozens of trolleys with doors ripped off, poles damaged, and windows smashed. 12,000 people were involved in the unrest at Kinnickinnic Station and were pushed back by police wielding tear gas. An estimated 10,000 people participated in a similar incident at the Fond du Lac car station, and 2,000 at West Allis Station. This group demanded the release of prisoners taken earlier by the police and were successful in getting these demands met. Rioting soon spread further as a group targeted Lakeside Power Plant in St Francis, TM's central generating station. One death resulted when a man broke through a window and touched a metal pipe to a high-voltage switchboard inside. Eventually, labor officials came in from Washington to settle the strike at high level, consulting directly with S.B. Way, TM's president at the time. Streetcar service was a total mess the next day, but this eventually recovered. The strikers' demands were also satisfied, but there were unintended consequences.

|

Samuel Insull, quite troubled

by both the SEC's actions and

his white moustache.

(Chicago-L.org) |

Unrest like this affected many cities' transit systems and helped convince the national Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that power utilities should divest themselves of transportation interests. This would help quench future labor disputes, as the thinking went, since transit systems would be managed by smaller and more local organizations as opposed to absentee corporate control. As stated before, this is how Samuel Insull lost his public utilities empire, including his three interurban lines. Furthermore, an unintended result in many cities, Milwaukee included, was the beginning of a switch away from rail-based transit. Bus service, it was thought by TM management, would be less susceptible to disruption by labor disputes in the future.

Before all that unrest and as traffic grew, TM looked for still more efficiencies and improvements to make, such as along the Lakeside Belt Line. This route formed a belt line (yes, really) around the south and west sides of Milwaukee's outskirts, and was built to bring coal to the Lakeside Power Plant. Construction began in 1928 and eventually wrapped up in 1932, with the line extending from the Muskego Lakes Division (the combined East Troy and Burlington interurban routes) at what was called Greenwood Junction. A northern section of the Belt was proposed but never built - this would have connected the west end of TM's Rapid Transit Line (more on that later) at West Junction to the MN Division at Brown Deer. The west end of the line ended up being little-used, except for interurban reroutes, fan trips, or the occasional shipment of miscellaneous freight from western connections.

|

A colour photo of the Milwaukee Electric's Lakeside Power

Plant service later in life, at St. Francis, WI, crossing

Kinnickinnick Avenue.

(Don Ross, Larry A. Sakar.) |

One notable exception were special trains and a temporary spur off the Belt, which carried construction workers and material to the site of Greendale, a model suburban village built as a WPA project (which still exists, but includes some modern urban sprawl too). The Belt's most important section was from the Milwaukee Road interchange at Powerton, through to the Lakeside Power Plant. This was such an integral piece of trackage that part of it survived all the TM interurban lines (except the East Troy) by a couple decades, and the streetcar system by one. Between Powerton and the lake, the Belt passed above the North Shore Line (with no interchange), met the MRK Line at Whitnall Ave, then crossed and interchanged with the CNW and city streetcar system at Kinnickinnic Ave, before proceeding into the power plant grounds. Steeplecab electrics hauled coal from the Milwaukee and C&NW interchanges, and ashes were taken down the line to be dumped. An employee shuttle service ran on the Belt between Kinnickinnic Ave and the plant.

|

Milwaukee Electric cars 929 and 946 (Both St. Louis cars)

meet at the Allis-Chalmers factory in West Allis, WI, 1954.

(Don Ross) |

Back in Milwaukee itself, city operations hummed along and received modernizations of their own, with “safety island” sidewalk platforms and new passenger shelters being built. Car barns (confusingly, these were always called “stations” by TM) were also rebuilt or expanded, including attached passenger loading areas to accommodate motor buses, which ended up being a predecessor to the modern “transit center”. The largest of these stations included Kinnickinnic, Fond du Lac and Cold Spring - the former two survive today, in rebuilt form, as bus garages, and most of Cold Spring's buildings live on in industrial and warehouse use. Cold Spring was more of a shop complex than a simple car barn, and included an erecting floor, two transfer tables, an electrical shop, wheel facilities, and more. Some “stations” actually were just that, without attached carbarns.

|

The Lake Park carhouse, one of Milwaukee Electric's many

beautiful and artful structures, combining art nouveau and the

Arts and Crafts movement. |

A couple of these included North Side Station at 7th, Atkinson & Green Bay, Farwell Station in the busy Lower East Side neighborhood, and Lake Park Station, a rustic affair serving its namesake park along Lake Michigan. Milwaukee city routes were quite varied, serving industrial, residential and commercial areas alike, many along the same route. Some lines ran crosstown, but most served the downtown core. Highlights of the city routes included: the busy loop at the CNW's lakefront station downtown. the Wells-Harwood line's private right-of-way alongside the Milwaukee Road main line in suburban Wauwatosa, the high, viaduct crossing of the industrial Menomonee Valley on the 27th Street line, the sharp residential-industrial transition along the Kinnickinnic line, and the leafy, laid-back atmosphere of the suburban route to wealthy Whitefish Bay and Fox Point (this had originally been built as a steam “dummy” line). TM also operated its own city lines in Kenosha, Racine and Watertown, and some of the smaller Milwaukee city cars were often shared with these properties.

|

Milwaukee Electric No. 713 at Fond du Lac Station, showing off its original, Peter Witt/CSL Sedan-inspired lines.

(Don Ross) |

|

Ex-TMERLCo. No. 801, now at the Fond Du Lac Training

School in Milwaukee, WI, 1955. Note the Hunter line signs. |

Though those city cars came from many builders, a TM favorite was the St Louis Car Company. Most cars, from the workaday 500s, 600s and 800s to the unique but troublesome center-entrance 700s, passed through Cold Spring Shops and received the unique touches and modifications. Some cars were built from scratch at Cold Spring and others, especially the interurbans, underwent radical surgery there. Patient success stories included some of the most unusual and notable streetcars and interurbans ever seen, designs idiosyncratic to Milwaukee. Among these were the open, party car 'Marguerite', festooned in lights, a fleet of St Louis-built cars converted to articulated units (these were later augmented by St Louis articulateds, which were ordered for South Milwaukee suburban service but ended up seeing city and interurban service in addition to their intended role), several cars from the same builder modified with more powerful motors and differing door arrangements, the home-built dining car mentioned earlier, and, most famously, the 1180/1190-series “Duplexes”.

|

Duplex No. 1182-1183 races towards the Racine station in Speedrail livery.

(Don Ross) |

|

The "Duplexes" in TM colors, on the eve of war in 1939.

(Frank Butts, Don Ross) |

These began a star-crossed history with the ill-fated Indianapolis & Cincinnati Traction company (I&C), a line which never reached Cincinnati, yet ordered several very large and heavy high-speed, all-steel combination cars in anticipation of this goal. Indeed, these were among the most substantial interurban cars ever constructed. They quickly proved to be much more than the I&C needed, and several went to the Union Traction of Indiana, some later serving with the Indiana Railroad. The remaining eight were purchased by TM in 1929 and converted into articulated units by cutting the cars in two just ahead of the rear truck and inserting a new section which included the articulated pivot, supported by a third, center truck. They were provided with MU controls and often ran in multiple with single cars on heavy schedules. They ran all the way up until 1950, a testament to their success. Back on the I&C, Cincinnati-built curved-side lightweight cars had replaced the heavy steel ones in 1928, but the economies realized by then these weren't enough to save the line, which was abandoned amid the Depression in 1932. In a bizarre twist of fate, after two other owners, the I&C lightweights ended up on TM territory for a brief stint of operation under, where they replaced the I&C combination cars.

|

The Rapid Transit Line at 28th Street in Milwaukee, showing

off the TM's iconic giant powerline gantries over the tracks. |

The Duplexes were almost synonymous with what was one of the most major and ambitious improvement projects ever conceived by an interurban: the Rapid Transit Line. This was to be a high-speed, totally grade-separated speedway into downtown Milwaukee, with multiple tracks allowing for local and express operations and terminating in the basement of the Public Service Building, accessed via a short subway. Overall, the goal was one held by many interurban companies, but attained by only a few: to remove interurbans from the city streets and vastly improve scheduled running times. As the TM was still directly involved with electric power generation and distribution at the time, the Rapid Transit Line also provided a new right-of-way for the company's high-tension power lines, with enormous structures supporting them directly above and integrated with the catenary support structures. Work began in 1924 and proceeded slowly due to muddy conditions brought on by unusually wet weather, followed by an unusually harsh (even for Wisconsin!) winter in 1925. The first section opened in 1926, from 35th Street, then the western city limit of Milwaukee, to a point called West Junction, some 4.5 miles away, where the line split, with cars for East Troy and Burlington (the Muskego Lakes Division) going south, and cars for Waukesha and Watertown (the Watertown Division) curving west. Watertown Division traffic began using the Rapid Transit Line in 1926, with “Local Rapid Transit” service being provided by 600-series city cars converted for one-man operation.

|

A prominent elevated section was known as the Hibernia St. Elevated,

seen here in the 1930s.

(Don Ross) |

Not long later, the western section was completed to 100th Street, joining the Waukesha interurban route, and around the same time, the southern branch to Hales Corners opened. The last, and most important, segment to open did so with unfortunate timing, in the late 1930 as the Great Depression was over a year into its course. From 35th Street to a point near 8th & Hibernia, the route cut into the north side of the Menomonee River Valley, requiring extensive excavation. Additionally, the City of Milwaukee stipulated that no street grade could be changed as part of the project, so utility relocation and new overpasses added to the construction difficulty and expense. Between 12th and just east of 10th Street, a steel elevated structure, intended to go further and connect with street trackage, brought the line over Hibernia Street and down into a two-level storage yard. This yard also contained a new express freight facility and a transfer area for TM's unique rail-truck service. A spur from the lower level ran up to the portal of the never-completed subway that was to bring the Rapid Transit Line into the basement of the Public Service Building. Instead, trains ended up using a “temporary” wooden trestle to street level, and used an alley, then 6th, Clybourn, and Michigan to reach the Public Service Building five blocks east. Despite the temporary/permanent nature of the downtown connection, the Rapid Transit Line was a success (at first), reducing running times by almost a half hour compared to the old routes using city streets alone. However, the effects of the Depression very quickly took their toll in reduced ridership. Already in 1930, the separate local service using the one-manned 600s was dropped and interurbans began making local stops as requested. This could be cumbersome, especially with the large Duplexes.

|

They didn't call it the Beer Line for nothing!

(Milwaukee Road Beer Line) |

Management had planned, and actually began, an extensive improvement project to bring the city entrances of other interurban lines up to “Rapid Transit” standards, starting with the Milwaukee-Racine-Kenosha (MRK) Line. This involved several reroutes off of streets, grade separations from railroads and highways, and dedicated station facilities in a few places, but the most critical element- the downtown entrance- was never realized, despite a proposal to route MRK trains via a circuitous, though marginally faster, route involving the Lakeside Belt Line. Instead, MRK trains plodded along congested Kinnickinnic Avenue to reach the Public Service Building. Rapid Transit improvements to the Milwaukee Northern Division barely even commenced, only resulting in a couple of grade separations with streets, one new station at Silver Spring Road, and one new bridge over a creek on the north side of the city. Plans for the Northern were perhaps the most grandiose though, with one scheme that almost did go forward involving electrification of the Milwaukee Road's famous “Beer Line” branch and a long subway under 6th Street to connect to the Public Service Building!

|

| A TM ticket, good for any transfers in all city limits. |

Unfortunately- and you probably saw this coming- all of these grand plans and improvements ultimately were almost for naught (despite the Rapid Transit Line delaying the inevitable and lasting until the 1950s). During the war’s boom years, many Milwaukee city lines (Racine and Kenosha's had already been converted to bus and trackless trolley) were completely rebuilt and other facilities were rehabilitated. One brand-new line was constructed, in 1942, to serve the Supercharger Company plant in West Allis (home to the Allis-Chalmers company). Ridership swelled on both the city and interurban lines, and any planned line abandonments or conversions to bus were postponed. Immediately after the war, TM management sought to retain riders who were quickly choosing the automobile, and heavily advertised their attractively priced weekly passes. These passes, valid on all buses, streetcar lines, and interurban routes operating within city limits, were very forward-thinking for the day, and similar passes and tickets would show up on transit systems nationwide in the following decades. Indeed, the basic style of that weekly TM pass would remain with only a few changes into the era of all-bus operation, right up until discontinuance of paper transfers and passes by the Milwaukee County Transit System in 2016.

I'm getting ahead of myself though.

|

Milwaukee's "The Transport Co." trolley coach No. 307

roars past the camera in an undated, unknown photo.

(Unknown source) |

The seeds of the mighty TMER&L’s downfall were planted during the waning days of the Depression, when the first cutbacks began. In 1935, the Public Utilities Holding Company Act was passed by Congress. The result for many interurban railways around the country, TM included, was the separation of electric power and railway interests. This was usually problematic at best and disastrous at worst, as profits from electric power generation and distribution often helped subsidize the same company's rail operations. In 1938, TM's electric interests were passed off to the Wisconsin Electric Power Company (WEPCo, although the former maintained a close affiliation with the latter) and the rail operations were reorganized as The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Transport Company (TM still), known to many and often advertised as simply the very authoritative-sounding “The Transport Company”.

|

The Port Washington loop under "The Transport Co.", after

getting service to Sheboygan cut off. |

The same year marked the beginning of the very slow end of the interurban system, when the Burlington line was abandoned, stripping St Martin's Junction (where the East Troy and Burlington routes split) of its “junction” status. In 1939, the East Troy line was cut back to Hales Corners, except for the section between East Troy and Mukwonago. 1940 saw the end of two lines, or rather sections of them; the northern portion of the Milwaukee Northern Division from Port Washington to Sheboygan in February of that year, and in September, the Watertown Division west of Oconomowoc. That line was further axed west of Waukesha in 1941, on the eve of Pearl Harbor. This was fortunate timing, as during the war, any further cuts were postponed and, as already mentioned, the system saw heavy wartime ridership. From 1941 until 1948, the TM interurban network reached as far as Port Washington, Waukesha, Hales Corners and Kenosha, and the city streetcar network, though nibbled away at beginning during the Depression, was still basically intact.

|

A 1946 Grumman MCI Courier, which Northland Greyhound

operated starting in 1946.

(GJ G.) |

At the end of the war, management made the decision to divest itself of all remaining interurban operations and scale back the city lines. However, despite being very successful with interurban bus operation previously, the company at this point had no interest in it, finding it easier to keep operating what remained until buyers could be found. The Port Washington line had already been sold in 1942, and the Waukesha line was the first after the war to be spun off, in 1946. Both lines went to local Greyhound operator Northland Greyhound. After six years of operation by that company, overseen by The Transport Co., the Port Washington line was let go in 1948, and the MRK Line, having been purchased by the Kenosha Motor Coach Company in 1946, was abandoned south of Racine in September 1948, with the remainder going in December. This left only the Milwaukee-Waukesha and Milwaukee-Hales Corners lines (and the slowly-shrinking city system), which were still respectably busy, and that brings us to the last gasp of the interurban system, a very short period crammed with enough activity to fill several years, a time that began with great promise, hope and ambition, and ended with disaster, disappointment and unfulfilled dreams.

|

Jay Maeder's high school senior photo in 1925.

(The Trolley Dodger) |

Enter Jay Maeder, a Cleveland businessman who had been a cadet at St John's Military Academy along TM's Watertown Division. As a regular rider during his schooling there, he was very familiar with the Milwaukee-area electric lines and was personally invested in seeing service continue. We can also assume some of this passion was also rooted in a fondness of the Cleveland-area electric lines as well, but more on that next month. Maeder and his associates purchased the Milwaukee-Waukesha and Hales Corners lines from Northland Greyhound, forming the Milwaukee Rapid Transit & Speedrail Company, more commonly known simply as the snappy “Speedrail”. Though The Transport Co. did not directly operate the lines, Speedrail still operated them under contract, guaranteeing fares and transfers would be kept the same as those under TM, and that the Hales Corners line would be operated on a cost-per-mile basis.

|

Ex-Shaker Heights Rapid Transit No. 301 works a service

through West Junction, bound for Hales Corner. |

Maeder realized that cost-cutting was the only reasonable way forward and began replacement (read: supplementation) of the heavy 1100-series Duplexes with secondhand lightweight equipment. These included the Indianapolis & Cincinnati cars mentioned above, which had been at work on Canton, Ohio's Inter-City Rapid Transit Company, and then the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit in Maeder's hometown of Cleveland, before coming to Milwaukee. There were six of these cars, just enough to cover off-peak service. In December 1949, the Maeder interests revised their contract with The Transport Co., part of which involved the transfer of all ten of TM's former South Milwaukee suburban 1030-series articulated cars, which, along with the Shaker Heights lightweights and a few remaining Duplexes, filled out the rest of the service requirements for Speedrail.

|

St. Louis-built interurban car no. 1112 reaches the end of the

Hale's Corner/East Troy line in 1910. Note the integrated

destination sign in the clerestory front.

(Don Ross) |

The other change to the contract was less positive. Speedrail now had to bear all costs of the Hales Corners line, living on fare receipts only. The after-effects proved to be quite major, but did not show up for a while, as fares and manpower were reduced by the implementation of a bus-like farebox and zone fare system, doing away with conductors in the process. Now that the Hales Corners line could be operated directly, schedule coordination with the Waukesha service was ensured, and service frequency was actually increased. Some passengers were attracted back to the line by the increased service, decreased fares, and at least newer-looking equipment. On December 5th, 1949, a small profit was shown. Very tentatively, Speedrail looked to be a success.

|

Milwaukee Electric No. 821 at the Cold Spring Shops

transfer table, May 5, 1950.

(Don Ross) |

But it was not to be, not in the slightest. As costs incurred by running and maintaining a diverse gaggle of old, second and third-hand equipment piled up, and with competition against the local buses and private automobiles only intensifying, losses were already mounting to the point of being unmanageable. Heavy maintenance was contracted out to TMER&T's Cold Spring Shops, and the charges for this were high, as was rent for the Public Service Building. Not only was the building Speedrail's downtown terminal and carbarn, light maintenance was also carried out there, and the building housed the company's offices. Management desired improvements to this situation by establishing a new car house and shop area east of Waukesha, but the funds just were not there. In January and February 1950, heavy winter weather and its associated higher operating costs and maintenance put Speedrail into the red.

|

M-14, originally a home-brew freight trailer, which was

involved in the second collision of 1950.

(Don Ross) |

Then, that February, Milwaukeeans got a bitter taste of what was to come. One of the articulated units and a Cincinnati lightweight collided at Sunny Slope, west of Wauwatosa on the Waukesha line. It was followed by a second accident, a runaway incident which destroyed M-14, Speedrail's only serviceable freight motor. Both received an inordinate and perhaps unfair amount of coverage in the local press, tarnishing the operation's image. It wasn't, of course, the case that travel by interurban was inherently dangerous, a view that the local public may well have been forming, but instead that maintenance and dispatching had slipped under the deteriorating financial conditions, contributing to the accidents. Regardless, the result was a loss of trust in the railway, just when many former riders were choosing car travel anyway.

|

| Speedrail Car No. 66 (sister to the 65) wearing the new Speedrail corporate livery. |

|

Chicago, Aurora & Elgin No. 301 (at right) before being sold

to the Speedrail.

(Unknown source) |

After the wrecks, one of the cars (No. 65) was repaired with a new front end and attractive new orange and maroon paint scheme that was to be Speedrail's new corporate image. That March, a small profit returned, and two more third-hand cars arrived on the property: former Aurora, Elgin & Fox River Electric cars 300 and 301, which had most recently operated, again, on the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit. It was not long before the 300 became merely a parts source to keep the 301 running, but the latter became regular equipment for the Hales Corners line. Unfortunately, the 301 turned out to be a very rough rider, not performing well at the high speeds of the line and was generally unpopular with the public. Speedrail's troubles did not escape the notice of Milwaukee's mayor at the time, Frank P. Zeidler, who realized the value of the line and wished to secure its future. He attempted to get the State of Wisconsin to give its blessings to a municipal authority to fund and operate Speedrail, but, this being the 1950s after all, Zeidler was accused of socialism (how horrible!), especially by rural legislators, and nothing was ever done.

|

Speedrail Articulated cars No. 39-40 pause at Brookdale Siding,

Greenfield, WI, before the unthinkable happened.

(Don Ross) |

Spring became summer, and as summer 1950 turned to fall, events were beginning which would seal Speedrail's fate. They began innocently enough, as the National Model Railroad Association was holding its annual convention in Milwaukee, and as part of the event, on Saturday, September 2nd, five special round-trip runs between downtown Milwaukee and Hales Corners were planned. Coincidentally, this date was also the first anniversary of Speedrail management. Extra precautions were taken that day, with extra dispatching personnel on duty and safety officers chosen from the management, on hand to double-check things, since more trains than usual were to be operating on the single track south of West Junction. Former South Milwaukee articulated unit number 39-40, just emerged from Cold Spring Shops in the company's new paint scheme, was one of the NMRA special cars that day, and Jay Maeder himself was the motorman. Precious few photographs of the 39-40 wearing its shiny new dress exist because of what happened next.

|

The heavier steel Duplex completely shredded the lightweight,

articulated 39-40 with a massive loss of life. |

The timetable called for the car to be northbound from Hales Corners on the double track north of West Junction, where it was to meet southbound Duplex 1192-93. For reasons that were never conclusively determined, the 39-40 was actually south of West Junction, on the single track. It was about 10:00am and the weather was clear, though the location, just south of the S. 100th & National station, was a blind reverse curve, partially obscured by trees. The 39-40 collided at speed with 1192-93, with the heavier Duplex overriding the floor of the articulated, splitting its forward unit right down the middle. Most of the ten people killed in the wreck were in this forward unit. Luckily, motorman Maeder and several others were able to jump to safety just before impact. The freshly overhauled 39-40 was totally demolished, too much to tow away, so it was scrapped on the spot. The wreckage was cleared away, the railfans dispersed, regular service resumed that evening, and the news media laid vicious blame on Maeder for the wreck, even further damaging Speedrail's image. The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin eventually determined that the wreck was caused by an incorrect interpretation of one of the Nachod-type signals protecting the single track. Duplex 1192-93 was badly damaged but survived intact enough to be towed back to the Public Service Building, surely not installing any trust in the company by anyone who saw its hulk being dragged through the Milwaukee streets.

|

Speedrail Lightweight car No. 64, just a few months prior

to her career-ending wreck. |

Almost unbelievably, another wreck happened just three days later, but this time without any fatalities or major injuries. Lightweight car 64 struck steel heavyweight 1121, which was serving as a freight motor at the time, at the C&NW interchange near West Junction. Number 64 was retired and scrapped, but the 1121 received minor enough damage to stay in service. The next day, Speedrail was informed that its public liability insurance would be canceled. A new insurance policy was obviously difficult and expensive to work out, but amazingly one was eventually worked out. Limited service using one car at a time as a shuttle was reestablished on the Hales Corners line, with service as normal on the Waukesha route. In November 1950, with costs of all kinds spiraling, the entire property was placed into a trusteeship of the Federal Court. The trustee, ironically enough a former TM superintendent, removed the Speedrail branding from equipment and timetables. The service was now operating simply as “Rapid Transit”. The company's new insurance lapsed in March 1951, and the state forced a 12-hour suspension of service.

|

The Lehigh Valley Lightweight being delivered to Milwaukee,

1949.

(TheTrolleyDodger) |

In the interim, “temporary” bus operations started between the Public Service Building and the Waukesha terminal. The company did get its insurance policy restored, but the duplicitous bus service continued operating alongside the interurban, siphoning a relatively small, but significant in terms of revenue, percentage of ridership away. In a desperate attempt to reinvigorate interest in the line, the company pressed a “new” car into service. This was another Cincinnati Car Company curved-side lightweight, built for the Dayton & Troy Electric in Ohio. Speedrail had acquired and refurbished it in 1949, and it wore Lehigh Valley Transit's striking red-and-cream livery while on the property. With a bright and refurbished interior, the car reinstated through service to Hales Corners, but this proved to be very short-lived. Losses were higher than ever, cash reserves were running dangerously low, and “no responsible group”, as the Trustee put it, could be found to operate the line. Drastic schedule cuts were implemented, and Mayor Zeidler again made one final plea for city control of the line, only to be shouted back with accusations of socialism again. Noble attempts by local citizens' groups to raise enough money to save the service were woefully inadequate. Abandonment was the only real option left open to the trusteeship.

|

Speedrail No. 63 in June 1951, making the last rounds in

Waukesha before abandonment.

(Joseph R. Chesen, Don Ross) |

Early in the evening of Saturday, June 30th, 1951, lightweight 63 made the last round-trip to Hales Corners, and articulated 37-38 completed the final run to Waukesha. For the remainder of 1951, various plans for the restoration of service were sporadically floated, all coming to naught. Also during this time, the current was turned on nightly, and a lone, empty “ghost” car ran back and forth in an effort to deter thieves from stealing the copper overhead wire. Finally, in spring 1952, the Hyman-Michaels Company of Chicago were deemed receivers by the court and dismantled the line. A number of years later, Interstate Highway 94 running west out of downtown Milwaukee was built directly on much of the right-of-way of the old Rapid Transit Line, a perverse testament to its excellent engineering. The massive Marquette Interchange, connecting I-94, I-43 and what became I-794, didn't have any use for the remnants of the line though, and completely obliterated the entire area around the Rapid Transit Line's entry onto city streets, including the Hibernia Street Elevated, the entire length of its namesake street, and the stillborn subway portal.

|

A GM New-Look "Skylight" bus exemplary of what took over

from what Speedrail left behind.

(Paul Kimo Gregor) |

But the story does not end there. The Transport Co. still operated Milwaukee's remaining streetcars and would for almost another seven years. The WPECo. had been wanting, since the end of World War II, to sell its remaining transit interests, and that included The Transport Co. It wasn't successful until 1952, when a new corporation took over, the Milwaukee & Suburban Transport Corporation (M&S, not the clothing brand). Oddly enough, the interests behind this new organization owned Indiana's Monon Railroad and the Indianapolis transit system. The latter’s conversion from streetcar to bus demonstrated their policy for Milwaukee, and streetcars had begun to be replaced by trolleybuses and outer ends of some routes by gas buses by the late 1930s.

|

| A condensed timetable of the Wells Street Car Line, circa 1957. |

After the halt for World War II, trolleybus and diesel bus conversions picked up speed, continuing until the last line left, Route 10-Wells Street, ended operations in the early hours of March 2nd, 1958. Ironically, its last days had been extremely busy, as it closely served County Stadium (today the site of Miller Park) for Braves games (the Braves since moved to Atlanta, and Milwaukee's home team has been the Brewers since 1969). On that final, nocturnal run, so the story goes, railfans and anyone else seeking a memento ripped out anything not bolted down- and some of what was- in that last car. Trolleybus operations continued in Milwaukee until the mid-1970s, when, in a mirroring of events in many other mid-size American cities at the time, operations of the financially-struggling M&S were turned over to the public in the form of the Milwaukee County Transit System, which still operates the Cream City's buses today.

|

Line car D22 and locomotive L4 on the Lakeside Belt Line

in 1964, after all other TM service had ended.

|

There is still a bit of an epilogue to the story of electric traction in the Milwaukee area. TM's power plants at Port Washington and St Francis (Lakeside), long since turned over to WEPCo, continued in operation until the early 1980s, converting from coal to gas in the mid-1970s. It was until this time that ancient steeplecab electrics still shuffled hoppers back and forth from the same C&NW to the plants. At St Francis, the old Lakeside Belt remained in operation from the C&NW interchange, where, over a decade earlier, the “last streetcar in Wisconsin” finished operating. This was an employee shuttle service, in its last years and on the final run using an 800-series city streetcar modified with a snowplow and large headlight, which ran between Kinnickinnic Avenue and the power plant. Its last trip was made in 1961, three years after public streetcar operation ceased in Milwaukee, and probably carried more railfans than employees.

|

Beulah Lake siding on the East Troy

Branch, 1937.

(Don Ross) |

A section of the TM also operates as part of a museum. By the time TM decided to abandon the East Troy branch, it had actually developed a significant carload freight business. This was mainly due to the fact that it was never touched by a “steam road”, but management saw it as a sure money-loser. The Village of East Troy disagreed, and at the abandonment hearing for the line, the Village leveraged the Wisconsin Public Service Commission into allowing freight service to remain, in the interest of “public service” (the legal definition, that is). Bonds were issued to fund the continuation, and operation passed to the Village. Ownership was still under The Transport Co., however, and when it divested itself of the line in 1949, full control was given over to the Village. The line was then officially renamed the Municipality of East Troy Railroad. Former TM freight box motor M-15 was the primary power for many years, although other TM equipment (including a rare, self-propelled differential dump car) was present. When a new steel tube plant decided to locate on the railroad in 1969 and did not want to electrify its spur, a search began for diesel power that culminated in a second-hand 44 tonner. The M-15 was still used on occasion, and the overhead trolley system remained intact and functional. Whether by diesel or electric power, freight service continued along the 7.5 miles between end-of-track in East Troy and the Soo Line interchange (in later days Wisconsin Central) in Mukwonago. Traffic declined from the 1980s onwards, until by the late 1990s, trucks had taken almost all of the freight.

|

South Shore Pullman interurban No. 13 passes original

Milwaukee Electric No. 846 at the East Troy Electric Railroad.

(Jonathan Lee) |

Fortunately, freight was not the only thing keeping the line going, otherwise the story would end here. As early as 1967, museum operations by The Wisconsin Electric Railway Historical Society began on the line, running alongside daily freight operations. TWERHS eventually became the Wisconsin Trolley Museum and took over operation, and eventually ownership, of the line as the East Troy Electric Railroad. In 2000, ownership passed to the Friends of the East Troy Railroad, and the historic equipment collection was expanded. In addition to many pieces of TMER&L and other Midwestern traction equipment, it now includes a sizable fleet of ex-South Shore Line heavyweight steel cars, modified to run with trolley poles rather than their original pantographs. These now provide the bulk of the passenger service. Freight only very rarely runs now, although a connection is still maintained in Mukwonago, now with Canadian National.

|

The new Kenosha Streetcar in operation, now a genteel

city park loop, with this PCC wearing Chicago Surface Lines colors.

(Jonathan Lee) |

Despite the success of the East Troy Electric though, it would be another 39 years before revenue-service streetcars returned to the state. A small loop line opened in Kenosha in 2000, 68 years after TM discontinued its streetcar service there, as part of a redevelopment project along the city's waterfront. It has now been in successful operation for twenty years, linking the Metra commuter rail station with downtown and the waterfront on a one-way loop. Though it mainly serves as a tourist attraction, it operates year-round and does have regular riders. Operation is shared between a non-profit group and Kenosha Area Transit; the cars use the same fare system as their city buses. Interestingly, the line uses a fleet of mostly ex-Toronto PCC cars (a design never originally seen in Wisconsin) painted in a rainbow of different liveries representing former PCC operators from across the country, including

Chicago Surface Lines.

|

A map of the new Milwaukee Streetcar, with the planned "L" Line displayed.

(The Hop MKE) |

The most recent chapter in this story started in the mid 2010s, proving that the history of mass transit is never really over. After decades of false starts and failed (and more ambitious) plans, the Milwaukee Common Council approved plans for a modern streetcar system on January 21st, 2015. Construction began in 2016 and finished two years later, with the first test run occurring on the night of June 18th, 2018, and public service commencing shortly thereafter. Smartly, the initial route begins at the Milwaukee Intermodal Station (the city's Amtrak and long-distance bus station) and runs through the burgeoning Third Ward, the downtown business district, the Milwaukee School of Engineering campus, and dense residential neighborhoods before ending at Burns Commons on the city's Lower East Side, not too far from the busy Brady Street restaurant-and-nightlife district.

|

The Hop in action, sporting an advertisement for its sponsor.

(Jonathan Lee) |

Originally known simply as the Milwaukee Streetcar (and sometimes still referred to as such), the system, like seemingly everything else today, had to have a corporate sponsor and this came with the sale of its naming rights. The Potawatomi Hotel & Casino entered into a twelve-year sponsorship deal, emblazoning the cars with its logo and naming the system “The Hop”, a clever nod to both Milwaukee's brewing heritage and the quick transportation provided by the streetcar. It may be a little garish, but the corporate sponsorship has a major perk for the riding public. The casino has, for now at least, committed to fare-free operation. There are provisions at stops for the installation of ticket machines, but for now, it's a free ride!

|

A snowy Hop passes the camera en route to the Commons.

(Jonathan Lee) |

In the modern era, private operation of transit systems is very rare, and The Hop is no exception, being run by global transit conglomerate Transdev instead. (Is it really private if they’re worldwide?) The system uses Brookville “Liberty” low-floor, double-articulated light rail vehicles, and incorporate a feature never tried (or technologically possible) in the old days of TM: off-wire battery operation. The same cars with off-wire capability are also proving their worth on new systems in Detroit, Oklahoma City, and

Dallas.

The section of the M-Line (“M” for Milwaukee, I guess) along Kilbourn Avenue and Jackson Street has no overhead wire, ostensibly for aesthetic purposes around Cathedral Square Park and the Milwaukee School of Engineering campus. The L-Line (“L” for Lakefront) also will have an off-wire section, again for aesthetic purposes, as it passes near the graceful architecture of and green spaces around the Milwaukee Art Museum, and passes through the Couture Tower - a project which has still not commenced, and is delaying opening of the line; everything except the section near and through the property of the new high-rise has been built. History does have a way of coming freakishly full-circle, as the L-Line closely parallels the old TM streetcar thoroughfares of Michigan and Wisconsin Avenues with traffic to and from the C&NW's lakefront passenger station (site of the Milwaukee Art Museum today), and the M-Line nearly duplicates a small section of the last regular-service streetcar route in Milwaukee, Route 10-Wells. The Hop’s current expansion plans in almost every direction are still active, so the future of Milwaukee's new streetcar system seems to be secure.

|

The Hop is also not above poking fun at itself, as this bus displays

during route training in preparation for the "Hop" opening.

(Jonathan Lee) |

The story of electric rail transportation in Milwaukee is at once unique and common to just about every North American city. It is a tale of dreams and ambitions, successes and failures, and ultimately rebirth. Like all electric railroads, the TM hit these themes in an entirely unique manner, from its homebuilt cars to its freight operations. Its legacy continues to this day, leaving its subtle mark on the shape and growth of the Cream City.

|

What's left of the Rapid Transit Line today at 32nd Street, Milwaukee.

(Jonathan Lee) |

-----

Welcome to the end of the line! We understand if your eyes are a bit tired from reading the huge amount of information we've imparted onto you this month, so we'll make our outro brief. Once again, thank you to

Jonathan Lee for the herculean task of writing today's episode and Nakkune for editing said herculean episode. Resources for today's post include

"TM, The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company" by Joseph M. Canfield (of which all photos today are credited, unless otherwise noted),

"The Electric Interurban Railways in America" by George W. Hilton and John F. Due, and a few

"First & Fastest" articles. If you would like to know more or support the East Troy Electric Railroad, follow their link

here. Next month we cover the two states of Indiana and Ohio, but until then, you can always follow

myself or

my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe

buy a shirt as well! Thanks for reading, and ride safe!

No comments:

Post a Comment