Chicago is home to many prominent civil engineering masterpieces: The Hancock Center, the Sears Tower (yes those are their names, fight me), and the many bridges that line the Chicago River. One architectural wonder that tends to go over people's heads, though, is the famous Chicago Loop circling Lake Street, Wabash Avenue, Van Buren Street, and Wells Street. Originally opened in 1897, the Loop not only serves as an essential part of any Chicagoland commuter but it is also an architectural marvel above and below with its reams of cross beams and ribbons of steel rail creating beautiful, functional art. Despite its shape, the story of the Loop is more of a tangled knot of four different strings coming together into one solid mass, like your headphones in your pocket. Join us as we uncover the hidden history above our heads on today's Trolley Thursday!

------

|

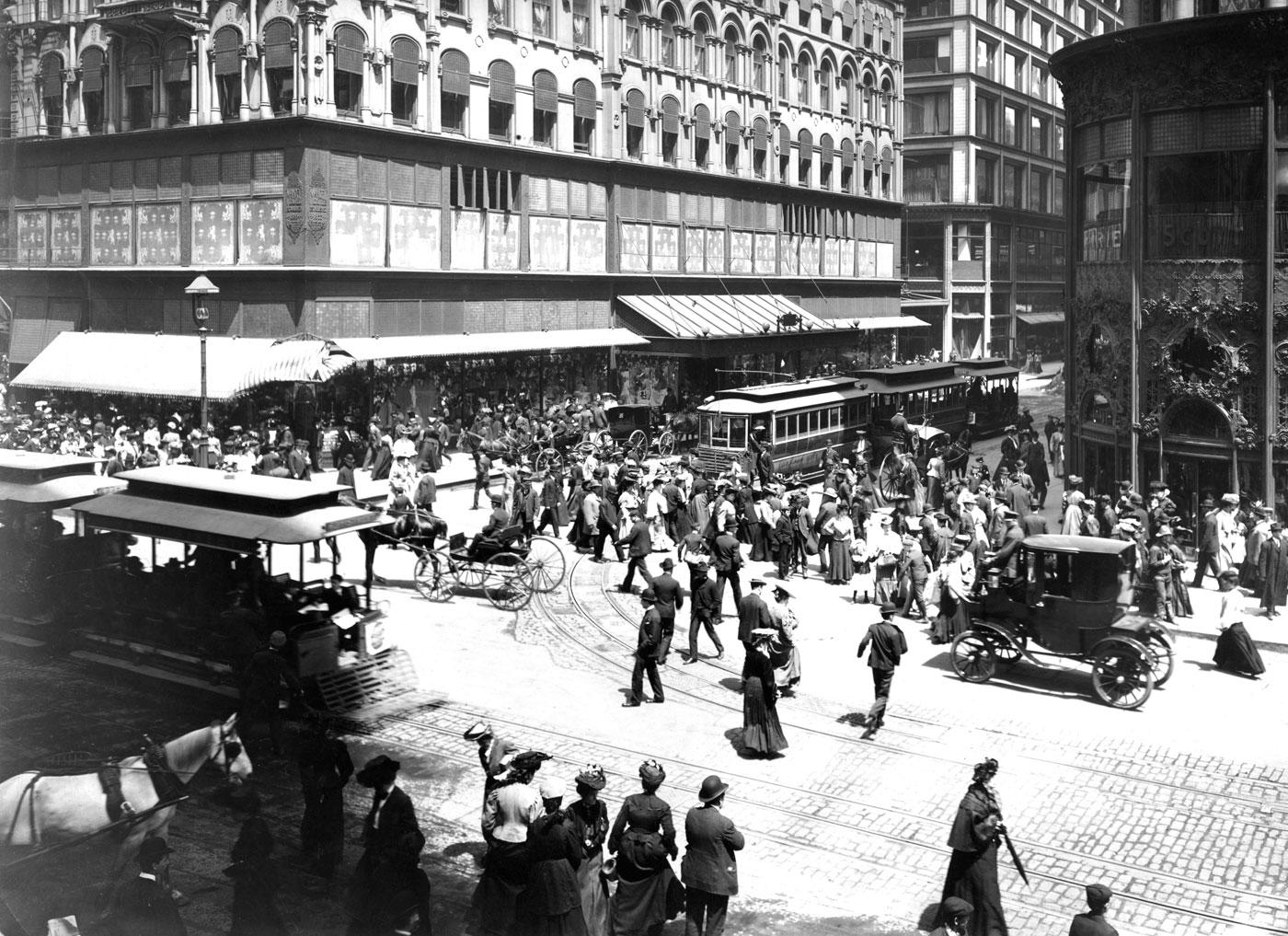

A cable car train trundles down Madison Street looking from State Street, 1890s.

(Chicago Herald and Examiner) |

In the early 1800s, Fort Dearborn was constructed on the banks of the Chicago River. When the fort was eventually decommissioned in 1837, the land was ceded to Cook County, IL, and became the seat of government for the Windy City. This area originally went unnamed, or was referred to as the "Dearborn" area of downtown, but this changed in the 1880s when cable cars began running under a motley number of separate street railway lines. Unlike the San Francisco cable cars that moved to single-car operations by this point, Chicago's cable cars always operated with a grip car as a locomotive and one or two trailer cars. Thus, enormous turnarounds had to be constructed to turn the train around, which had the benefit of increasing service coverage over several blocks. As many of these lines converged on downtown, the area began to be referred to as the "Loop".

|

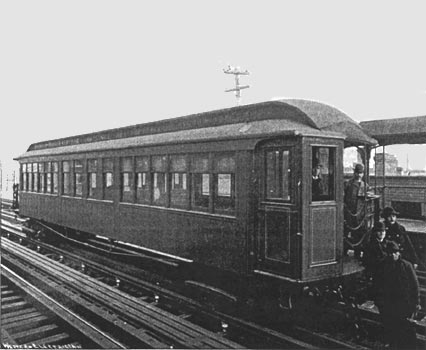

Same location as above in 1904, showing the heavy pedestrian

traffic along with the cable car trains still hard at work.

(Chicago Transit Authority |

A constant problem that only grew in the days of the cable car was heavy street congestion. Even around the Loop, streets at rush hour were packed with horse-carts and streetcars, and it was commonplace to find that walking was much faster and cheaper than riding. With a city as dense as Chicago, inner-city rapid transit seemed superfluous and civil engineers instead began looking outward, hoping to bring passengers in from areas the cable cars were too uneconomical to reach. There was also the problem of the cable car service going down every night for line maintenance, meaning night owls lacking personal transportation had a hard time getting home. To solve all of these issues, railroad planners began looking upwards for inspiration.

|

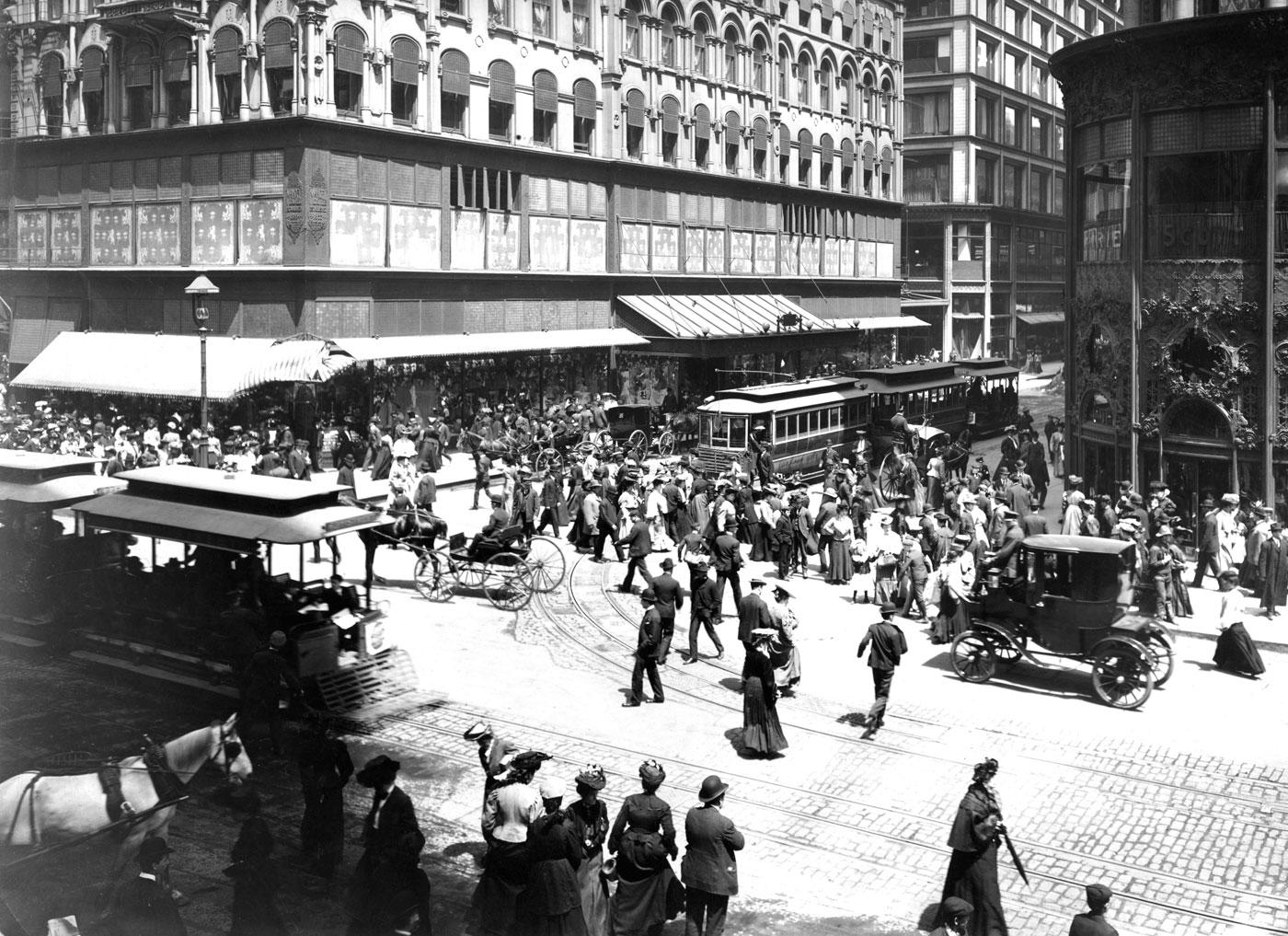

A northbound South Side L service pauses at Indiana Avenue,

looking east along 40th street. The street tracks belong to the

Chicago Junction Railway.

(Discover Live Steam) |

Elevated railroads were nothing new by the time the Chicago & South Side Rapid Transit Company (better known as the "South Side L") was incorporated on January 3, 1888. By the time it was chartered on March 26, 1888, the railroad was routed from somewhere between Wabash and Dearborn streets at Van Buren down to 39th Street (then the city limits, now Pershing Road) and powered by steam locomotives. One stipulation in the charter was letting uniformed policemen and firemen ride for free, which the modern Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) continues to honor today. By 1890, in the middle of the South Side L's construction, an international committee in Chicago chose Jackson Park as the site of the World's Columbian Exposition. Not wanting to miss out on the potential ridership, South Side L planners began planning a route south and east to Jackson Park via 63rd street.

|

An 1890s map of the South Side L with

the line out to Jackson Park at bottom right.

(Chicagology) |

By early 1892, the railroad ordered 20 Forney-type tank locomotives from the Baldwin Locomotive Works and 180 passenger cars from Gilbert Car and Jackson & Sharp, both prominent coachworks. Their plan for the Jackson Park route ended up slightly modified, as their original plan on using a private right-of-way put the railroad dangerously close to private property and thus needed the owners' consent. Instead, it was now routed over East 63rd Street, then sparsely populated, which also had the benefit of saving time. The route following Van Buren and 37th Street gave the South Side L the popular nickname of "The Alley L", as it paralleled an alley adjacent. On May 27, a six-car train headed by a "Forney" steam locomotive ran the 3.6 elevated line from 39th Street to Downtown to officially open the line with 300 guests aboard. Public passenger service between 39th Street and Congress Street began on June 6, 1892.

The second elevated line to open following the success of the South Side L was the Lake Street Elevated Railroad (or Lake Street L), which was chartered on February 7, 1888, and opened on November 6, 1893 as the second permanent elevated line in Chicago. The original plan, suggested by Joe Meigs of Cambridge, MA, involved using a steam-powered monorail system of his design, but this was deemed too outlandish and standard Forney locomotives were chosen instead. The Lake Street L had a relatively short life before the infamous Chicago Traction Wars, as its original owners spent much of its money arguing their original franchise was too restrictive (necessitating a new 40-year city franchise in 1890). When the railroad was sold in 1892 to pay off an enormous dept of $17 million ($481 million today), the new owners were able to open the first section between the corner of Market & Madison Street to California Avenue on October 28, 1893. It was then extended out to 52nd Avenue (Laramie) by April 23, 1894.

|

New Forney steam locomotives from Baldwin arrive on the Lake Street L in 1894.

(Science Source) |

|

He is Charles Yerkes, and you will obey.

(Science Photo Library) |

However, all was not well on the elevated lines. The South Side L had experienced sinking passenger numbers since the end of the World's Columbian exposition and went into receivership in October 1895. It would not find a new owner until June 1897, when the new South Side Elevated Railroad Co. acquired all physical assets. The Lake Street L, too, was under new ownership in 1894 when Charles Yerkes purchased a controlling stake and began using the Lake Street L as a lynchpin in what eventually became the "Union Loop". With a bit of the "oil of palm" (bribery), the Lake Street L was allowed to build an extension between Market Street and Wabash Avenue via Lake Street, becoming the Northern Leg of the Union Loop on October 1, 1894. This was only the beginning of Charles Yerkes' grand plan to unite his transit holdings.

|

A 1919 postcard of the "Met" crossing the Chicago River

over Jack-Knife bridge by Gerson Bros, Chicago.

(Public Domain) |

Yerkes' other elevated railroad holding, the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Company (known as the "Met" or "Polly L") was incorporated under the same people behind the Lake Street L and planned to go between Downtown and Chicago's West Side as laid out in their charter. The railroad first operated on April 1895 under third rail power, a benefit from hiring Frank Sprague to convert all of Chicago's Ls (more on that later), and a test trip between Canal Street to Garfield Park was run on April 17. From the time the third rail started up to the opening of the Union Loop, the Polly L expanded out with separate branches to Logan Square (Northwest), Garfield Park (which was already finished for quite some time), Humboldt Park, and Douglas Park.

|

A contemporary representation of the Lake Street L

wreck at Rockwell Street, June 13, 1896.

(Chicago-L.Org) |

Around this same time, it was quickly being realized that running steam locomotives in a dense metropolitan city, with coal cinders dropping onto the street, sooty black smoke staining the surrounding buildings, and the noise and rattle of it all, was not the best idea. Frank Sprague, the famous streetcar inventor and pioneer, was hired to start work on converting the South Side and Lake Street L's in 1895, as well as design the infrastructure for the Polly L. The steam locomotives on the Lake Street L were set aside by June 13, 1896, but was briefly reinstated after a new electric train derailed and fell onto Rockwell Street. Part of the cause may have been the new motor trucks but this was never confirmed.

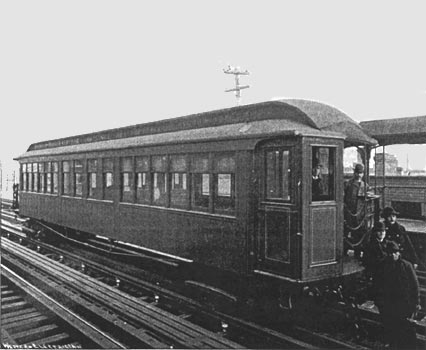

On the South Side L, Sprague not only got to work on converting the line to electricity, but he also put forward a concept that had only existed on paper up to that point: multiple unit working. Before this, even the longest electric train only had one locomotive car and several trailers behind it; now, one could realistically couple multiple motored cars together with bi-directional controls on every car. When this was first shown on November 12, 1897, the Chicago Herald-Time declared it "an unqualified success". Additionally, Sprague upgraded the cars with electric heaters, motors, trucks, controls, and braking system along 120 of the 180 South Side L cars, with the only major problem being faulty rheostats.

|

One of Frank J. Sprague's electrically-converted coaches being tested on the South Side Elevated, December 11, 1897.

Note the motorman's shack next to the open deck.

(Insulator Reference Site) |

|

A modern suvey map of the Union Elevated Railroad,

as submitted to the Library of Congress.

(Library of Congress) |

The Union Elevated Loop, which combined The Lake Street L, South Side L, and Metropolitan L, along with the Union Elevated and Union Consolidated railroads (which were also under Charles Yerkes, finally opened on September 6, 1897 after a period of slow, steady construction and corruption between 1894 and 1896. Financed by Yerkes' scandalous ability to bribe the city legislators, the Loop was met with intense criticism from both private property owners who were now infringed on by a private utility and other railroads (like the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin) that wanted access to the Loop but had to pay a fee, which jacked up commuter fares. His successful swindling of a 50-year franchise for all his loop operations (through bribery, what else?) enraged Chicagoans so heavily that he was driven out of town and forced to move his "medicine show" of business to New York.

|

A Northwestern Elevated Train at Argyle Street in 1916.

(Public Domain) |

Following Yerkes' exit, The fourth and final loop railway was the Northwestern Elevated, which was originally backed by Yerkes himself, but he never had anything to do with it. The railroad seemed to have an odd bad luck with charters, as their first proposition in 1894 was rejected by Mayor John P. Hopkins for being "too vague." It took three tries for the mayor to approve their charter, but by the time their original December 1897 opening loomed, the railroad had to suspend construction work from Dayton to Buena Avenues due to financial difficulties. The Chicago aldermen, now increasingly frustrated with the delays and seeing the Northwestern seemingly reneging on their charter, gave them until January 1, 1899 to get their act together and open their line.

The Northwestern L seems to have taken this with the same energy a student with "senioritis" has because by the time the railroad "finished" construction on Christmas, 1899, only one track was completed between Wilson Avenue (their initial terminal) and Kinzie Street (their Loop access point). In having one track and a few stations with construction started, they could at least prove their franchise was still valid to the bare minimum. When a test train went out on New Year's Eve, the Chicago Public Works commissioner derided the Northwestern's slap-dash construction and revoked their franchise on the grounds the elevated structure was "incomplete and unsafe."

|

Visual representation of the Northwestern L bypassing every

roadblock the Chicago Police Department can throw at it, 1900.

(Densha De D) |

Not wanting to back down, the Northwestern Elevated ran a second train on January 2nd, but this time it was stopped by police and the crew were arrested. One of the company officials, possibly not in a right state of mind, then took to the controls and sped off, bound for the loop. Police tried to block their way by raising the Wells Street bridge and blocking their Kedzie Street route with railroad ties, but the Lake Street Elevated proved to be a worthy ally as they allowed the Northwestern L to come through the Loop on their line. Having made their point, the now-exasperated Chicago aldermen granted them one more franchise extension until May 31st. The railroad kept true to their word and opened all stations and two tracks on that date. Hilariously, the Northwestern L approached the city counsel one more time to propose a franchise serving the Ravenswood neighborhood, but by contemporary reports, the counsel was "in no hurry to approve it."

|

A Northwestern Elevated Railroad Co. Baldwin Steeplecab,

S-105, originally built in 1920. Note the pantograph and third

rail shoe.

(A.F. Scholz) |

All four of the Loop Elevateds continued to grow out and expand all through Chicago, providing reliable and convenient service for all commuters, but by the late 1910s, the four companies were looking to consolidate, much like the Chicago Surface Lines consolidation of 1913. Under direction of utilities magnate Samuel Insull (remember him?), the Chicago Elevated Railways Collateral Trust engaged in a series of discussions that laid groundwork for financial agreements, free transfers, and simplification of routes that allowed all four companies to run trains on each others' lines. When the talks concluded on January 9, 1924, the Chicago Rapid Transit Company (CRT) became the new operating body of the elevated and, like the CSL, all were allowed to keep their original names, schedules, and services. Some, like Northwestern L, even expanded into freight service and purchased a fleet of Baldwin-Westinghouse steeplecabs for local freight interchange with the Milwaukee Road at Lawrence and Howard.

|

CRT's Logo Pin for employees.

(Gopher500) |

|

A Niles Center-bound car arrives at Main Street, Niles Center.

Year Unknown

(George Trapp) |

Expansion came quickly under the CRT, as they were able to buy bankrupt portions of other independent railways to bring it under their control (like the Chicago & Oak Park Elevated), while also building newer lines west out of Chicago. The most prominent of these lines was the Skokie Valley high-speed bypass, intended to provide local service alongside the North Shore's limited interurban. Then called the Niles Center branch, it opened on March 28, 1925 between Dempster Street (Skokie, then Niles Center) and Howard Terminal. Other additions that followed included the Chicago, Westchester & Western bypass for the Chicago Aurora & Elgin (in the same capacity as the Niles Center branch) along the Polly L, and the three story Wells Street and Legan Square terminals. The CRT even operated its own funeral car service in conjunction with the

Chicago, Aurora & Elgin, which is detailed in the post linked within.

|

1920s-era CTA cars 4271-4272 approach Main Street Station

on the Niles Center Branch (now the CTA Yellow Line) on a

Chicago Electric Railway Association fan trip in 2014.

(Ed Graziano) |

Like with all of Insull's properties, the CRT had to be given up by 1932 due to his huge losses in the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The new owners were CRT President Britton I. Budd (no relation to the Budd manufacturing works) and Chicago Public Works Commissioner Albert J. Sprague (no relation to Frank Sprague). Between them, they would help the CRT along through the 1930s and 1940s to keep it above water until operations would be assumed by the new Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) in 1947. Much of the original rolling stock from the pre-consolidated era continued to operate into the 1960s, and many survivors are now in private museums and also maintained by the CTA for heritage excursions. The loop continues to see use after over 100 years in service, but the rest of its story will have to wait for next week.

|

The famous intersection at CTA Control Tower 18, where Wells Street and Lake Street meet on the

Northwest Corner of the Loop. Truly a work of functioning art.

(Daniel Schwen) |

------

Well, yikes, this ran longer than I thought! I know this seems like I ended it prematurely, but I promise to slow down and elaborate more when I write about the CTA next week. I'd like to credit

Jonathan Lee for serving as this month's Chicago transit expert, as always, and my editor for suffering through my word salads. If you would like to learn more about the history of the Chicago Loop, the elevated railroads or the Chicago Rapid Transit Company, hit up

Chicago-L.org and tell them the motorman sent you. Until next week, you can follow

myself or

my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe

buy a shirt as well! Ride safe out theah!

No comments:

Post a Comment