Even if you're not into railroads, the name "Pullman" is synonymous to luxury. Indeed, one of the many things George M. Pullman's company was well known for was building luxurious sleeping cars that made going across the country, or across a state, a luxurious first-class affair. However, through all of the fancy trains and the various worker strikes and the admittedly-creepy paternal industrial culture Pullman championed, one of the more subtle and long-lasting products his company made were streetcars and elevated railway coaches. Electric railway companies around the country, especially around the Chicago area, were loyal buyers of Pullman products, and today's Trolley Tuesday will cover just a taste to close out this month!

-----

|

George M. Pullman - railroad car magnate, odd soul patch aficionado.

(Britannica) |

|

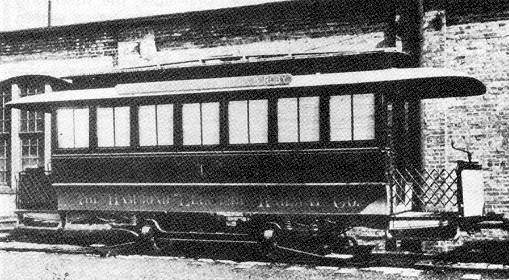

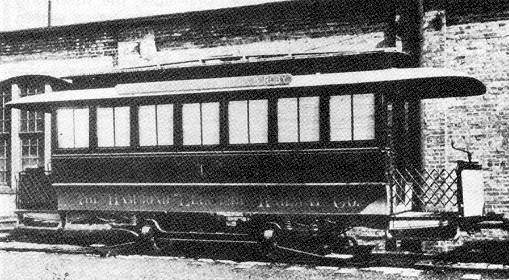

One of the early Pullman horse-drawn streetcars from 1891.

The name reads "The Hammond Elk and [Indistinguishable] Co."

(Mid-Continent Railway Museum) |

Before George Pullman died in 1897, following the Great Pullman Strike that shattered his belief in industrial paternalism, he decided to branch out his enormous palace car monopoly by entering the streetcar market in 1891. At this time, electric streetcars were at its infancy as Frank. J. Sprague had only patented his trolley pole and traction motor patents in 1888, so Pullman began with making horsecars. Pullman was entering a dense market, as J.G. Brill and St. Louis Car Company (its local competitor) had footholds in the market, and the electric railway and interurban boom of the 1900s only tightened their grip. Building streetcars was certainly something different than building passenger cars, as these cars had to be small, light, and spartan to save on costs.

|

The "Sunbeam", perhaps the only original Pullman horsecar to last into the electrified era.

CSL/CTA repurposed it as a party car, then as a storage car. It is presumed being scrapped here.

(Joe L. Diaz) |

|

CSL "Big" Pullman 183 crosses Ashland Blvd along Roosevelt,

January 15, 1937. The car to the right is a Brill product, No. 5502.

(The Trolley Dodger) |

The biggest boost to Pullman's streetcar market came when

Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) ordered 948 streetcars between 1908 and 1910, and the South Shore ordered an enormous fleet of steel interurban cars in 1912. The CSL order was split into two classes, the "Big" Pullmans (101-700) and the "Little" Pullmans (751-1100) You might be aware of the enormous gap in classes, well the order was so big that the Pressed Steel Car Company had to supplement the gap. The Pullman cars were built to the same standards as the Brill cars. They were topped with a clerestory roof, had two wooden decks hanging off the main body, and a front that was a standard design based off both Brill and new competitor

Perley A. Thomas. This enormous class made up the bulk of Pullman's street railway products, but they were having a better time in the interurban market.

|

Southern Pacific's 1913-built Pullman interurbans rush along

the street with a three-car train somewhere in Oakland in 1938.

(W. Wainwright) |

Pullman started the 1900s by building wooden interurban cars to the same standard as their passenger coaches, with companies like the

Chicago North Shore & Milwaukee purchasing them and being praised for their swiftness and smoothness. During the early 1900s, wooden cars fell out of favor after some serious accidents highlighting their dangerously fragile construction. Pullman began making steel interurban cars in 1913, when the Southern Pacific's East Bay Electric operations in Oakland ordered 16 steel cars based on their venerable "Harriman Standard" commuter coaches. These cars were dubbed "blimps" for their enormous 72-foot length and 111-seat capacity, and they proved Pullman had staying power in the steel car business.

|

The long-lived South Shore Pullmans, which lasted from their

introduction in 1926 to retirement in 1982.

(Chuck Zeiler) |

As the 1920s continued on, they made hundreds of thousands of interurban cars for the

South Shore,

Chicago Aurora & Elgin, North Shore Line, and companies around the country like Los Angeles' Pacific Electric, New York's Interborough Rapid Transit, and heavy rail operations like the Illinois Central. All of these products were outshopped with help from Baldwin-Westinghouse (who provided the trucks and traction motors), and General Electric (who provided the relays and control stands). Both crew and passengers alike enjoyed the heavy sound deadening and ease of operations these new cars provided. The interurban era, however, did not last long, and it would take some new products to keep Pullman viable in the street railway sector.

|

A CTA trolley bus passes a fan trip on Irving Park Road, just

beyond the North side "L" to Buena Yard, May 30, 1954.

(Bill Hoffman) |

This opportunity for new products started in 1929, when Pullman purchased a controlling stake in the Standard Steel Car Company. With the Standard Co. came the Osgood Bradley Car Company, whose factory in Worcester, MA, was retooled as the Pullman-Standard Car Company factory. To capitalise on their new expanded market, Pullman began developing the "Trolley Bus" in 1931 to meet the growing demand as cities like Chicago, Seattle, and New Orleans converted many streetcar lines to trolley buses. On the

Chicago Transit Authority (CTA), plenty of trolley buses plied the old routings of many of its streetcars, often side-by-side with a later Pullman product from 1934: The Presidents Council Committee Car, or PCC.

|

CSL No. 4001 broadside for a factory-fresh photo at Pullman-Standard, Chicago, 1934.

(Hicks Car Works) |

|

CSL No. 4001 being swarmed by onlookers at its debut at

Adams & State Street, July 9, 1934.

(Hicks Car Works) |

As we've previously covered in the CSL episode, Pullman was one of two companies (the other being Brill) tasked with developing the PCC prototype in time for the 1939 Chicago World's Fair. Pullman developed the "Model B" with Westinghouse, who provided the incredibly-smooth and fast-accelerating multi-point controller that gave all production PCCs a rapid turn of speed unlike any streetcar, while the body construction was a revolutionary all-Alcoa aluminum frame and body. The car was so lightweight that even the trolley pole and the truck frames were made of aluminum, giving it a total weight of 29,600lbs. (An average "Big" Pullman streetcar was 53,000lbs.) It entered service on July 8, 1934 as CSL No. 4001 as the most futuristic streetcar in the entire fleet, with its Brill-built sister No. 7001 being slightly less outgoing.

|

Car No. 4001 later in its life, along with its sister, Brill No. 7001,

in storage at CTA's South Shops in the early 1950s.

The blue and white paint scheme is pre-war.

(Bill Volkmer) |

Unfortunately, this meant that CSL No. 4001 was an odd duck, as she would enter and reenter the Pullman-Standard Chicago shops for further modifications (like opening windows, lower door panels, a louder gong (which was originally aluminum too!), new door interlocks, etc.) When the production PCCs first emerged from Pullman in 1936, they sold in small numbers (1,052 overall compared to St. Louis' 3,534.) but crews found them much easier to work on compared to their St. Louis Car Co. counterparts. Railroads such as the Baltimore Transit Company and Pacific Electric wholeheartedly enjoyed their PCCs (with Pacific Electric getting the only double-ended Pullman PCCs), and Pullman continued to enjoy street railway success under their new guise.

|

Pacific Electric Pullman PCC No. 5010 (built in 1941) works a Brand Blvd. service on the Glendale/Burbank line, 1948.

(Ralph Cantos) |

|

The old 5000-series (Bombardier made a new 5000-series later)

proved their worth on the "Skokie Swift" when ridership far

exceeded expectations. This set, No. 51, is now preserved

at the Fox River Trolley Museum in one piece.

(David Sadowski) |

However, the times changed again and street railways were largely out of vogue by the mid-1950s. Pullman ceased trolley bus production in 1952 with the last order going to Valparaiso, Chile, and their street railway aspirations turned to elevated railways after 1947, with their Chicago factory closing in 1955. When CTA wanted to replace their aging 4000-series elevated car fleet, both St. Louis Car and Pullman were tasked with building an articulated "L" car out of their already-venerable PCC parts. The 5000-series made its debut in 1947 with only four examples, and this was due in part to the cars being three permanently-coupled cars that made maintenance a nightmare. Nevertheless, they served well into 1985 as they ended their careers on the Skokie Swift, while Pullman found work with the CTA again in 1964 with the new "High Performance" 2000-series.

|

CTA 2000-series No. 1992 in resplendent Pullman green and gold lining at the IRM,

celebrating the centenary of the South Side Rapid Transit.

(John Smatlak) |

|

The NYMTA's R46, the last major light rail vehicle built by

the Pullman Car Company. Many still operate like this one,

on the BMT Astoria Line just past 30th Avenue in Queens.

(GeneralPunger) |

It seemed Pullman found its niche in the 1960s making street and elevated subway cars alongside their budding commuter coach fleet. Popular customers included the Boston MBTA buying their "Bluebird" and "Silverbird" cars between 1963 and 1969, Cleveland's RTA buying "Airporter" cars in 1967, and New York adding the long-lived R46 subway car between 1975 and 1978. However, the R46 was also the last class of cars Pullman would make. Like its competitor, St. Louis Car, Pullman could not diversify itself beyond railroads and they couldn't compete with air and road dominance by the mid 1960s. After pioneering the Amtrak Superliners in 1982, its designs and assets were purchased by the Canadian company Bombardier, and the Pullman Car Company ceased to exist by 1987.

|

The historic fleet of Valparaiso Pullman trolley buses, including

the Pullman-Standard buses along the right, January 13, 2008.

(Ankara) |

Today, the Pullman Car Company lives on in its many sleeping cars and the many streetcars and trolley buses that continue to roam around the world. The PCC Model B currently survives under slow restoration at the Illinois Railroad Museum with its CTA and Chicago interurban kin, while the Valparaiso trolleybuses continue operating in Chile as a rolling historic landmark. Plenty of Pullman's other steel interurbans, streetcars, and trolley buses also survive in varying states of operation and display, from Perris, CA's Pacific Electric No. 418 (ex-Southern Pacific/East Bay Electric 4614) to Baltimore Street Railway No. 7407 at the Baltimore Streetcar Museum. Though these products are not as glamorous as the sleeping cars that share their name, they continue a legacy of quality, quickness, safety and comfort as promised by George M. Pullman.

|

Illinois Central No. 1198, one of many motors and trailers built for their electrified commuter service in 1926,

trundles along IRM trackage in preservation.

(John Chuckman) |

-----

Thank you for reading today's Trolley Tuesday all about the Pullman Car Company! Next week, our Chicago expert

Jonathan Lee takes you through a brief tour of the Milwaukee streetcar system, and I would like to say a preemptive thanks to you, the reader, for giving us some of the best readership we've had in the one-and-a-half years I've been writing this blog and the half-year Nakkune has been editing it. If you would like to learn more about the history of the Pullman company beyond the streetcars, please visit the Pullman Museum in person or online through

this link. You can also find more about the history of CSL No. 4001 through

Hicks Car Works. Other than that, until next week, you can follow

myself or

my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe

buy a shirt as well! Ride safe out theah!

No comments:

Post a Comment