Chicago has had a legendary reputation in American railroading as being the hub of some of the most famous railroads in the country, and its famous meatpacking plants made the creation of the refrigerated railroad car almost inevitable. While many famous names rolled in and out of its stations like the Santa Fe, New York Central, Pennsylvania and the Milwaukee Road, Chicago also led the way with its revolutionary street and elevated railways that covered what locals called Chicagoland, the boundaries of which are pretty culturally nebulous. On this month's series of trolleyposts, we look at the rapid transit of the "Urbs in horto" and see what worked for the Second City, starting at street level with the Chicago Surface Lines! Just please, eat your Polish sausage outside the car.

The first streetcars to run in the Second City started in 1859 with the formation of the Chicago City Railway Company (CCR) and was run with horse-cars. Another company, the North Chicago Street Railroad Company, began similar operations by 1861, and from the beginning the animal-powered omnibuses proved inadequate, being slow and quite expensive. By the 1880s, the Andrew Hallidie system of cable railways started serving as substitutions for horsecars, stating with the CCR in 1881 and adding on the Chicago Passenger Railway in 1883, and the West Chicago Street Railway in 1887. This made the system the largest cable railway in the world, and both the North and West railways came under the control of a man named Charles Yerkes.

|

Charles Yerkes, Conquistador of the Curled

Moustache and the Cable Car

(Illinois New Bureau) |

Yerkes was born to a Quaker family on June 25, 1837 in Philadelphia, but by 1881 found himself seeking new fortunes in Chicago, eager to rub big shoulders. However, his actions soon rubbed these big shoulders the wrong way as he and his business partners performed a series of hostile takeovers to completely buy out the North and West street railways. These railways came with controversial 99-year franchises under the Summer 1863 "Gridiron Bill" that proposed granting the then-dozens of street railway companies in Chicago a 99-year franchise. In January 1865, this bill passed over then-governor Richard Yates' veto as the "Century Franchise" or "99-Year Franchise Act". By the time Charles Yerkes entered the picture, mayor Carter Harrison Sr. negotiated with streetcar companies in 1883 to give them a 20-year franchise and decide the extended 99-year franchises later. This is the background for what would be dubbed by historians as the

Chicago Traction Wars.

In summary, considering we have so much more to cover, Yerkes tried to back plenty of public works projects (such as the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin) to pull the public on his side, but political machinations got the better of him. He won his campaign to push the "Allen Bill" through, enabling a Yerkes-controlled City Council to basically give him a 50-year franchise thanks to State Representative Charles Allen, but also jacked up the fares to a nickel ($1.54 in 2020 dollars) with low compensation back to the City under a proposed "Lyman Ordinance." Public opinion was so hostile to the Allen Law, seeing the potential monopoly under Yerkes, that on March 7, 1899, the Law was repealed and Yerkes himself sold his stocks in the street railways and moved to New York, later to help develop the London Tube.

|

CSL "Small" Pullman 588, emerges from the east end of

Washington Street Tunnel. Note the steep 10% grade

in and out of the tunnel, 1920s.

(George Trapp) |

Speaking of the Tube, the city had its very own cable subway crossing underneath the river. LaSalle, Van Buren, and Washington Streets all crossed the Chicago River at such awkward impositions for the cable cars that railways owners found it difficult to honor the ships accessing the city's port using the river. Not wanting to use the shallow street-level bascule bridge like one sees today (imagine the engineering challenges building a cable that splits when opened), the cable cars decided to reuse two old tunnels 18 feet under the river crossing over to the North and West side at LaSalle and Washington, respectively. The two opened on March 26, 1888, with the Van Buren Tunnel opening on July 27, 1893 due to slow construction. By the time electric wires replaced cable, an errant ship ran aground on the Washington Street tunnel and the Federal Government mandated their removal. All were closed to traffic by October 21, 1906. However, by some miracle, the tunnels were later rebuilt for streetcar use. Washington St. Tunnel operated until 1953, LaSalle until 1939, and Van Buren until 1952.

|

A Chicago Surface Lines fare token.

(Chuckman's Photos) |

So where were the trolleys in all of this? Well, by the 1880s, the Calumet Electric Street Railway on the South Side of Chicago was already in operation and this threw the other companies in a tizzy: on one hand, they spent so much money building cable lines up and down the city; on the other hand, here was a brand new piece of railway technology that was cheaper to maintain than animal or cable and could span farther away from the city. By the mid 1890s, in the middle of the Traction Wars, most lines had converted, with all by 1906. However, this still left the system a cluttered mess of different traction lines and, due to the Lyman Ordinance, the city had reserved the option to buy out the entire system for municipal operations once the franchises were up. By 1913, the Unification Ordinance made it clear: all lines now came under the operation of the municipally-owned Chicago Surface Lines. (CSL).

|

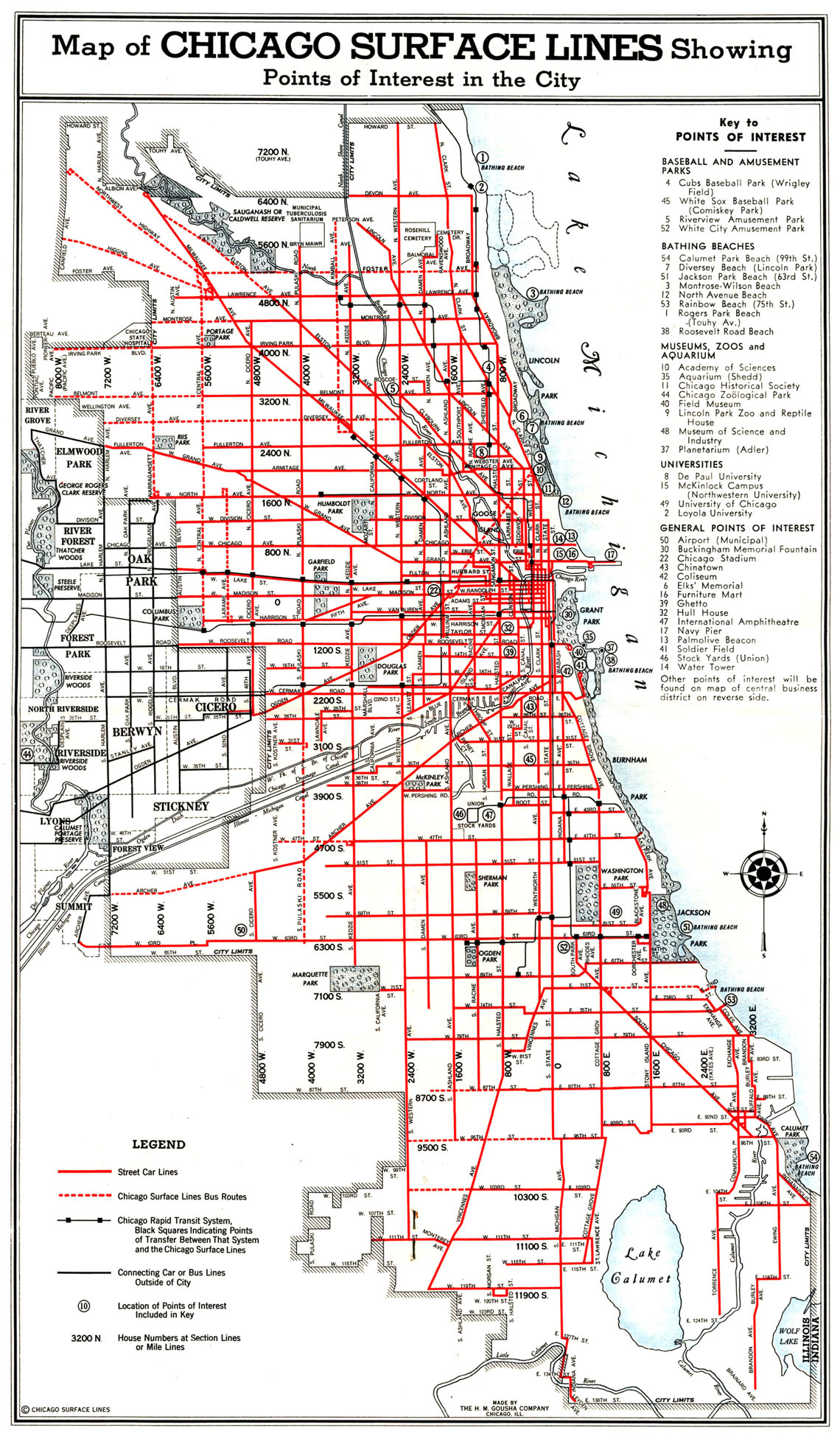

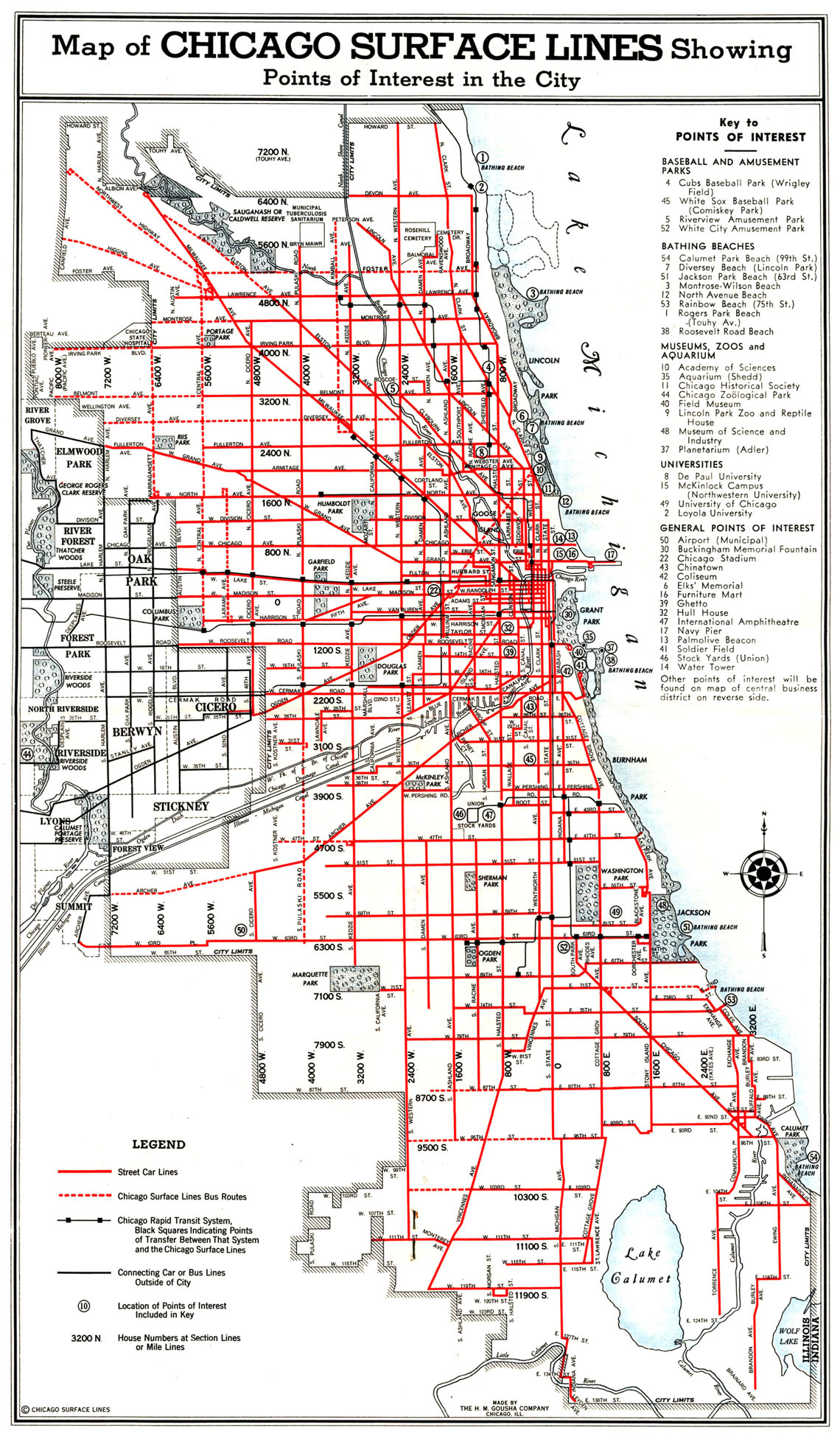

A CSL map dated 1937, at its peak.

(Chicago in Maps) |

Four companies made up this operating agency: The Chicago Railways Company, Chicago City Railway, Calumet and South Chicago, and the Southern Street Railway. Unified operations began in 1914 and the system at that point was growing to exceed 1000 miles over shared and consolidated track routes, with the longest single line following Western Avenue from Berwyn Street to 79th, a distance of 15 miles. That would be normal for an interurban, but this was a street railway line, especially when the Western Ave. route was extended to include Howard street in the North and 111th street in the South, bringing the final mileage to 22.65 miles. Due to the nature of the CSL, all four companies more or less operated in harmony and sported the most liberal transfer privileges in the world. Each collected their own fares, but none ever made an attempt to step on the others' territory or buy out, preferring to serve as regional transit options.

At this time, the streetcar fleet was quite varied as well, given all four companies purchased their own stock from a variety of manufacturers including Pullman, American Car, and St. Louis (all the usual suspects). These cars were all painted red with a cream window band following the consolidation of the Chicago Surface Lines. CCR used what they called "Big" Pullmans numbered 101-700, clerestory-roofed standard streetcars built to the standard Brill pattern with separate decks hanging off a big body. These were further supplied by copycat cars from the Pressed Steel Corporation, cars 701-750, and "Little" Pullmans filling in numbers 751-1100. A notable class of cars were built by the Chicago Union Traction Co. (CUTCo., no relation to Ron Popeil) in 1899, dubbed the "Bowling Alley" cars for their incredible length and full-length sideways seating. Other non standard classes including Birneys, CRR homebrew "Flexible Flyers", Peter Witts, Kuhlman cars on the Chicago & Southern Traction, the list is understandably endless...

|

Ex-CUTCo. "Bowling Alley" 1494, now lettered for CSL, works a charter service around 1914-1915.

(George Trapp) |

|

CSL Pullman Pre-PCC prototype No. 4001 on display at

State and Adams Street, July 9, 1934.

(Hicks Car Works) |

This all changed in 1934 when Chicago Surface Lines 4001 rolled into town for the second year of the Century of Progress International Exhibition. The car was one of two prototypes built for the Surface Lines by the Electric Railway President's Conference Committee (ERPCC), made to save transit companies from considerable money loss and prove that street railways could compete with the rising tide of automobile and bus traffic. President Guy A. Richardson of CSL was part of the ERPCC in 1934 and wanted two prototypes built to the standards set by his companions. Brill and Pullman-Standard were contracted to make this brand new car, using garish art-deco curves and motifs to help the car blend into the Century of Progress fair and made single-ended like the new Peter Witt "sedans" delivered in 1929. The car was 50 feet long, seat 58 passengers, and featured a unique 3-2-1 door system with 3 front entrance doors, 2 center exit doors, and 1 rear exit door to facilitate faster boarding. Pullman-Standard bragged in its spec sheet, the cars "demonstrate the latest in the arts for trolley car construction and to reflect the studies and development carried on in late years."

|

Brill prototype PCC No. 7001 poses outside the 18th Street

World's Fair gates with a horsecar that CSL also restored for

the event.

(Bill Wulfert) |

The other prototype, Brill No. 7001, caused a stir when it arrived in Chicago on March 1934. Pullman No. 4001 arrived later on July 6, and both sported swanky aircraft aluminum bodies that, when fully laden, weighed 55% less than the "Big" Pullmans. That July proved to be very hot, however, and Pullman 4001 learned it the hard way when its sealed windows and forced-air ventilation couldn't keep it from being an oven. CSL went back to Pullman's Chicago plant in August and had the car fitted with two-pane sliding windows, which Pullman did provide but they were made of chrome-plated steel rather than aluminum. Further issues like the accelerator overheating, the brake cylinders yanking on the aluminum floor, the lack of open-door interlocks (to prevent movement with the doors open), and a quiet gong needed were all addressed by the time went into official service on August 28 for the Century of Progress Fair.

|

The new streetcar bridge over Roosevelt Road for the 12th Street Car Line. The car will cross the Illinois Central here

and terminate at the Field Museum. Year unknown, possibly 1950s.

(David M. Laz) |

|

CSL Peter Witt "Sedan" 6317 meets a bus at Ewing and 105th,

year unknown. The bus is on the 103rd street beat, one of many

"Bustituted" streetcar routes.

(Joe L. Diaz) |

In order to access the big event, the line along Roosevelt Road was extended across the neighboring Illinois Central tracks to access the fairgrounds. This wasn't the only extension occurring as Chicagoland was sprouting with a veritable variety of streetcar suburban connections. Companies such as Evanston Railways, Chicago and Interurban (Later the Chicago and Southern), Hammond, Whiting and East Chicago, and the Chicago & West Towns all provided connections to the CSL to further spread the streetcar lines out into Indiana, Chicago's western suburbs, and North towards Michigan, all eager to connect with the CSL. In all, 101 lines spanned the length and breadth of Lake Michigan's southwestern coast, served by a massive fleet of over 3100 streetcars and 152 trolley buses, including 683 production PCC cars from St. Louis and Pullman Standard. Buses were also used to supplant lightly-served areas, starting in 1927 and being assisted by trolley buses starting in 1930.

|

CSL "Big" Pullman 594 passes Pullman PCC 4131 at Madison

and Wells, 1947. The two are on the eve of CTA ownership.

(CERA Archives) |

However, no World's Fair or War could change Chicago Surface Line's fortunes. Despite spending the 1920s and 30s riding high on both increased ridership and war effort importance, the CSL on the inside was completely and utterly bankrupted. The Chicago Railways, Chicago City Railway, and Calumet and South Chicago all fell into receivership by 1930. No matter how hard the transit companies worked to keep their services afloat, it did nothing to hide that they were now operating on a budget as thin as a trolley wire. Some 31 trolleys lines were even cut back to save on costs, making way for cheaper bus and trolley bus routes. By 1944, various trustees were appointed receivers of the CSL's constituent companies and on October 1, 1947, the Illinois state government formed the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) to receive the purchase of the Chicago Surface Lines. Now in the postwar era, the largest street railway in America was entering uncertain waters and who knew what came next?

No comments:

Post a Comment