-----

Part 1: The Allure of the Air Line

|

| (Grace's Guide) |

|

A 1902 Seaboard Air Line advertisement |

Before cross-country air travel became the quickest way between Point A and Point B, the "air line" was the most direct method (by rail) to travel the farthest distance in the shortest amount of time. This concept was originally pioneered by Sir Isambard Kingdom Brunel, an English engineer who designed a broad-gauge (7.25 feet) railway between London and Bristol that was supposed to be straight and flat. This was due to his large locomotives being unable to climb hills, and a flat railway meant faster speeds, even if it meant drilling through mountains and filling in valleys.

When introduced in America, the concept quickly gained hold as a means for primitive high-speed rail. Both heavy- and light-rail applications were abundant in the early 1900s, from the famous Seaboard Air Line between New York and Tampa, FL, to the Philadelphia & Western Norristown High Speed Line. You'd think a straight-as-the-crow-flies railway, ignoring all the geography involved, would be so easy a baby could design this railroad. Unfortunately, one railroad went on to prove the "air line" concept was more flawed than we think.

Part 2: The Great Air Line Scheme

By the 1900s, high speed interurbans like the Chicago Aurora & Elgin and the Pacific Electric gave plenty of electric railway promoters the idea to push this concept to its absolute extreme. A 1903 test from Siemens & Halske in Berlin also proved interurbans had the capacity to travel at high speed, as a three-phase AC railcar set a world record at 120 miles per hour. This gave Alexander C. Miller, an Aurora, IL, resident and chief dispatcher of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) an idea: why not invest in a brand-new electric railroad, using his own railroad signalling block system (which he invented) as part of the infrastructure?

|

| The official publication of the Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad, only for shareholders. The locomotive depicted was the planned high-speed third rail electric locomotive, but it was never built or even designed. (Chicagology) |

|

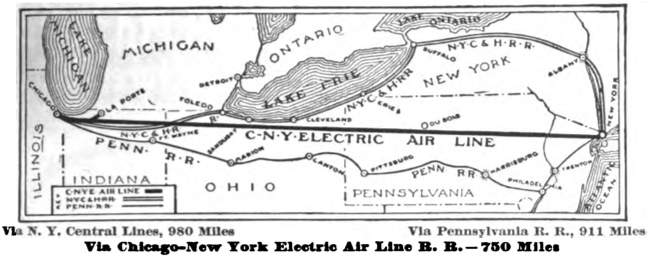

| The proposed Air Line route map in 1907, showing that a straightedge should really come with better responsibility and training. (Public Domain) |

In July 1906, Chicago newspapers began an advertising campaign that proclaimed 20,000 $100 shares were up for grabs in the new Chicago-New York Electric Railroad Air Line Company (CNYER). Unusually, or perhaps suspiciously, the railroad was attracting money primarily from shares rather than from bonds, short term loans, or even an existing conglomerate. The concept was almost laughably simple as well: A $10 fare guaranteed a passenger a 10-hour, 100-mph average journey from Chicago to New York on a 100-foot right of way. Grades would not exceed 1%, if any at all, there were no at-grade crossings to worry about, and locomotives would be powered by a third rail. Towns and cities would be bypassed, but feeder spurs would connect locally to Toledo, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. This entire railroad severely undercut the existing New York Central 20th Century Limited and Pennsylvania Railroad Pennsylvania Special/Broadway Limited, both of which took 20 hours to reach Chicago

| The more things change, the more they stay the same. Hyperloop, much? (Minneapolis Journal, November 4, 1906) |

Part 3: Construction and Chicanery

![Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad [closeup], cir… | Flickr](https://live.staticflickr.com/7922/32051861797_2ce7f7db8f_b.jpg) |

| Interurban Car No. 102, a later purchase for the Valparaiso & Northern subsidiary, poses somewhere in Laporte or Porter County with esteemed guests, 1910. The car was built by Jewett in 1900 and later became a funeral car until 1918. Note the "Chicago" script faintly above the center window. (Steven R. Shook.) |

Ground broke on the New York-Chicago Air Line on September 1, 1906 at La Porte, Indiana, one of the feeder towns for the interurban. Two interurban combines were purchased by the construction firm Goshen, South Bend & Chicago Railroad (GSB&C, under the CNYER) from the Niles Car Company and, quite boldly, both displayed a prominent "Chicago New York Air Line" scroll with one end reading "Chicago" and the other reading "New York"; after all, if they were only going between two cities, it doesn't make sense to change the destination signs, does it? A car barn was also erected in South La Porte for the two cars, along with a new power plant. Now that the project was nationally known, over 15,000 shareholders ponied up $2,000,000 for the construction and eventual operation of the Air Line. You might think this is a very tiny amount of money to provide for a 742-mile long, straight-as-an-arrow quadruple-track railway with all the earthmoving and infrastructure needed to construct and maintain this futuristic railway and... you'd be absolutely right.

Almost immediately, complications sprouted up. Construction was disquietingly slow, with three bridges over the Pere Marquette, Mono, and Wabash Railroads taking a considerable amount of time. These lay on the 17.5 mile section of main line between South La Porte and Goodrum, the latter town named after one of the major shareholders. A single track was also only laid, using 60-lb rail (an interurban standard) rather than the as-advertised 85-lb steam railroad standard. Trolley wire was strung up as a temporary method of power as the two interurban cars made demonstration runs to please the shareholders, along with the opening of a trolley park west of the Pere Marquette bridge. However, by the time the Air Line needed the capital to cross the tiny Coffee Creek west of the Wabash Railroad's line, that $2,000,000 had run out after the bridge and fills were completed. By the time the Air-Line opened its service to Goodrum and opened on November 1, 1911, only 21 miles of track were completed.

|

| A comemorative plaque in South La Porte, one of the only remnants of the Air Line. (IN.gov) |

Part 4: The Gary Railways

|

| A Gary Railways excursion for the Central Electric Railfan's Association in 1938 aboard 1927 Kuhlman-built streetcar No. 19, bound for Gary. This is the first CERA excursion ever. (Lamar M. Kelley) |

These ongoing, extraordinary, and somewhat suspicious events led the shareholders to eventually realize the obvious: this was not going to work. Even before the line to Goodrum opened, an alternate plan was being conceived to connect to the local streetcar network in Gary, IN, and save some face. Under the new firm Gary Connecting Railways, the new line to East Gary was hastily constructed on the Air Line's authorized route, but cut back before it could meet the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at Babcock, IN. This line opened on January 6, 1912. To keep the company financially afloat, the Gary Connecting Railways began investing in freight exchange with the Michigan Central Railroad in Garyton (now part of Portage) and the power plant in South La Porte was shut down in favor of public electricity. The last action committed by the now-former Air Line was establishing a streetcar line in Indiana Harbor called the East Chicago Street Railway, which was incorporated on July 23, 1912, and opened on February 15, 1913. I'm pretty sure nothing ever came of it.

|

| Gary & Valparaiso No. 50 (yet another subsidiary), built by the G.C. Kuhlman Car Company in 1918. It was later rebuilt as a snowplow in 1928. The offset center entrance and baggage door are disquieting. (Don Ross) |

|

| Gary Railways No. 12 (Cummings Car Company, 1926) is seen in living color at the Nickle Plate Railroad Crossing, May 2, 1949. (Don Ross) |

By 1913, the Air Line holding company reorganized itself as the Gary & Interurban Railway (G&I) after purchasing the local railway of the same name. All the companies were consolidated, including the Valparaiso & Northern (another feeder line established in 1908) and the Chicago-New York Air Line Railroad was officially wound up. (Mr. Miller could not be reached at this time for comment, it's not known for sure whether he really advocated for such an ambitious railroad or was just operating a stock swindle.) However, the new G&I did not last long, as the city of Gary refused fare increases that led to the company defaulting on bond payments. Things were made worse when one of the Air Line combines met its end colliding with a GSB&C locomotive at Air Line park on New Years Day, 1916. Three people were killed and twelve injured after the wooden car telescoped and was sent for scrap. The final ignominy was when the G&I was broken up and sold on September 18, 1917, with the Air Line tracks out to Goodrum scrapped later that November. What was left became known as the Gary Street Railway.

|

| The Gary Railways at its greatest extent, with the Kennedy Ave. and Chesterton Branches abandoned. (Shore Line Interurban Historical Society) |

|

| The Gary Street Railways logo. (Don Ross) |

The Gary Street Railway operated successfully around the town, serving the American Sheet & Tin Plate Company. A line ran out to Miller, IN along Lake Street, bringing more expansion to the fractured interurban, but this came at the consequence of abandoning the Indiana Harbor-Hammond, IN line (which was later handled by another Interurban. Another part of the former Air Line, the Gary & Valparaiso ran from Gary to Valparaiso & Chesterton, but the latter town switched to bus service by 1922. By 1925, the surviving Gary Railways were consolidated, yet again, under the Midland Utilities Corporation of... Samuel Insull. After Insull lost control of Midland Utilities, the street railways were swift of converting to buses. The last interurban car ran on October 22, 1942, with the last streetcar in Gary running on February 28, 1948. Freight traffic had actually ended in 1917, after the GSB&C Railroad was completely abandoned. For all its initial history, the Gary Street Railways operated successfully and lasted quite long, but the history of that famous fiasco remains. In his 1943 Electric Railroad Association article, Commander Edwin Jay Quimby opined:

And as time goes on, electric railroad enthusiasts will visit the right-of-way over which the original construction work was done—and some of the more imaginative individuals will hear the deep-throated whistle of a big palatial interurban as its spirit still streaks along this romantic pike, and they will catch a glimpse of the golden inscription CHICAGO on one end of the car as it flashes by, and NEW YORK on the other end—hurrying, hurrying—for 36 years have passed since it started on its swift way and it hasn't reached either place.

Part 5: The Singer Company's Small Electrics

|

| Singer Mfg. No. 1 handles a cut of six LS&MS boxcars, probably full of Singer furniture. The fancy scrollwork was later removed in favor of straight-green paint. (South Bend Tribune) |

On the other side of the same coin, a much smaller operation in Indiana became a ubiquitous example of an electric industrial railroad. As South Bend was the plentiful center of industry, being both close to a river and plenty of eastern seaboard railroads heading west, many factories took advantage by moving their plants and facilities closer to the railroad lines. One of these was the famous Singer Manufacturing Company, which was originally set up in 1868 as a hardwood cabinet factory. This later moved closer to the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway (LS&MS) line in 1902, allowing an expanded 60-acre facility with railroad tracks right in the yard. Normally, steam switchers were standard for an industrial application, but Singer could not risk it with their business involving wood and, eventually, sewing machines.

| A builder's photo of Singer No. 1 upon delivery. The trolley bell can be seen above the side window. (Harry Zillmer) |

| Singer Mfg. No. 4 works a hopper car beat at the South Bend works, year unknown. (Kevin Byrne) |

|

| Singer Mfg. No. 1 on display at ITM's former Noblesville location, long since out of operation. (South Bend Historical Society) |

When the Singer Plant closed in 1955, locomotive number 1 was sold to Bob Selle and stored at the Illinois Electric Railroad Museum (now just the Illinois Railroad Museum). Selle lived in Illinois at the time, but when he moved back to Indiana, the locomotive moved with him and found a home at the nascent Indiana Transportation Museum (ITM). Upon Selle's divestment of the locomotive in 1971, the ITM restored the locomotive to operation and ran it before putting it back on display. When the ITM was evicted from Noblesville's Forest Park, the Singer No. 1 was moved to a private, temporary storage on July 10, 2018. Though it is still in private ownership, the locomotive has since been sold to the RAIL Foundation of Michigan City. It is still up in the air where it will go, but the little locomotive still lives.

Part 6: Comparison's Sake

| This took me 10 minutes to make. Why even? (The Motorman) |

By now, you might be wondering: Why even compare these two at once? Well, my editor and I see it this way: It's a chance to not just recount the perspectives of two unique railroads, but also the extreme distances that these railroads ran on; one wanted to cover 700 miles between two major metropoli, while the other ran in just 60 acres. Furthermore, both of these stories go beyond just a simple "this town had a trolley line and now it's gone", as like with the Kennecott Railroad the industrial application of electric railways are forever fascinating. After all, it's why this blog exists in the first place: to tell the unique stories of any and all electric traction railroads all over the United States and all over the world.

-----

Watch your step as you alight onto the platform and thank you for reading with us! The sources from today's episode is from the 1943 issue of Electric Railroad Association magazine by Edwin Jay Quimby, which you can read here, and the South Bend Tribune's article on the Singer Electric Railway here. Next week, we leave Indiana's interurbans behind and look at Ohio's rich streetcar history! Until then you can follow myself or my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe buy a shirt as well! Ride safely, now!

No comments:

Post a Comment