Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (519-430BC) was a Roman civic and military leader, and dictator, whose legacy is one of simple and faithful leadership. Twice ascended to dictator (back when such a term was neutral or positive rather than negative), Cincinnatus relinquished his power peacefully to the Senate after his duty was done, even at his old age, without any fuss or delay. His understanding and control over the temptations of absolute power made him a figure in civic values, and others like President George Washington have taken his "call to agriculture" to heart. Similarly, the streetcars of Cincinnati served their city with the same faithfulness displayed to the city's namesake, but unlike the famous dictator, the Cincinnati Street Railway's time came much too early, even for a system just shy of operating for 100 years. Today, we look back on the Cincinnati Street Railway with fond memories and find out just what made this system so unique.

-----

Pre-Electric Uniqueness

|

A colorized photo of the East End carbarn in the early 1890s, on Eastern Avenue.

The car's final destination is the Little Miami Railroad Depot and Music Hall.

(Cincinnati Views) |

|

The "Grand Union" at 5th and Walnut in 1893.

The line is in the process of electrification, as horsecars

are still being used at this time, along with cable cars.

(Getty Images) |

The first horsecar line opened in the city of Cincinnati on September 14, 1859, when the

Cincinnati Street Railway Company (the first one) opened a single-track loop line between the city's West End and downtown. Five other companies soon followed, including a line stretching across the Ohio River into Covington, Northern Kentucky, to provide for the city's 115,000 citizens. In 1873, most of the city's street railways (including the Cincinnati Street Railway Company) merged to form the

Cincinnati Consolidated Railway. As the city further defined the operational procedures for the horsecar lines, one interesting set of rules was divided: the standardization of a 5' 2.5" streetcar gauge to not only fit companies that used 5'2" (Pennsylvania Trolley Gauge) and 5' 3" gauges, but also to ban big, scary, and dirty steam locomotives from running in the city. This rule was implemented around 1880, when further consolidations birthed the modern

Cincinnati Street Railway Company (CSR).

|

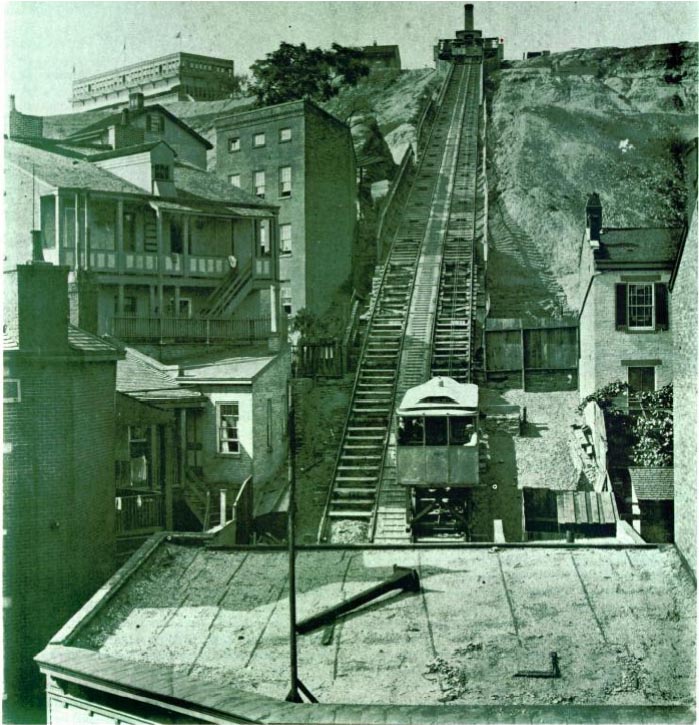

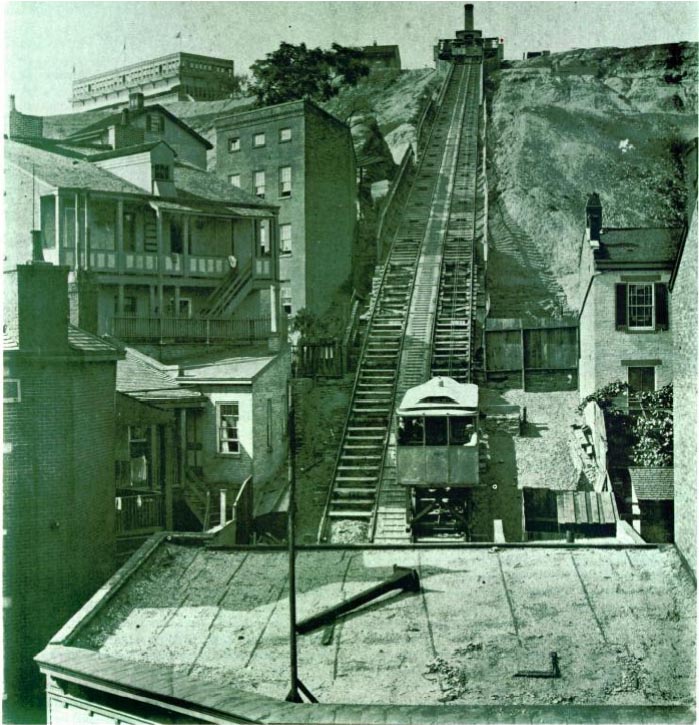

The foot of the Mt. Adams Incline,

which ran 19 hours a day as both

an important commuter line and a

tourist attraction.

(Cincinnati Refined) |

Despite the availability and ruggedness of horses, they couldn't scale the many hills that surrounded Cincinnati on the Northwest end of the Appalachian mountains. Eager to open up more of the city to the profitable street railways, the CSR devised a system of five "inclined plane railways" between 1872 and 1892. These interesting railways used a steam engine to lug two counterbalanced flat sections of track up and down the steeply-slanted grade on a wide gauge track. These were different from a funicular, as the inclines had two sets of rail lines rather than two lines sharing a common rail. All were originally separately-transferred, enclosed cars before being permitted to allow horsecars, then rebuilt to haul streetcars.

The

Mt. Auburn Incline, or "Main Street Incline", first opened in 1872 and was the oddest of the bunch as it was much steeper at the bottom. This was also the only incline to have an accident, as in 1889, a car failed to stop at the top of the incline and ran away back down, killing all but one. It was closed in 1898. The

Price Hill Incline was the second to open in 1874 and carried both passengers and freight wagons, but never hauled streetcars. The third, the Bellevue Incline, originally opened to pedestrian traffic but was rebuilt to carry streetcars in 1890. The

Mt. Adams Incline opened the same year as the Bellevue, in 1876, and was considered the longest lived incline with the Price Hill incline. Bellevue closed in 1948, while Price Hill closed in 1943, both ending their days carrying buses up the inclines. The last to open, and perhaps the shortest lived, was the

Fairview Incline built for the CSR's "Crosstown" line. With no safe way connecting McMillan to McMicken street, the streetcars had to use the incline. This was eventually rebuilt in 1921 for pedestrian use, reversing the usual trend.

|

The foot of the Mt. Auburn incline, showing the slight kink in elevation.

(Geocaching) |

|

A Mount Auburn Cable Railway grip car,

showing the two sets of "grips" on the bottom,

between the wheels.

(Jeffrey B. Jakucyk) |

Realizing the limited nature and the inconvenience of the inclines, Cincinnati needed a better way to connect the hilltops to the more developed downtown. This was where the cable cars came in. Starting in 1872, the

Walnut Hills & Cincinnati Street Railroad Company began a rival service to the Mt. Adams Incline. Interestingly, the operations of this line up Gilbert Avenue were not very good, as a 30 minute one-way trip up involved unhitching the horses at the bottom of the hill, fitting a detachable grip to drag the car up, then rehitching the horses and removing the grip. This was later remedied on October 1, 1886, when the cables were extended south to Broadway and north to Woodburn Avenue. The second cable company was the

Mt. Auburn Cable Railway, which opened in 1887. These were much simpler in operation, using double-ended "grip" cars and a series of trailers to run between 4th/Sycamore and Reading Road, with crossover switches removing the need for turntables. When the CSR purchased the Mt. Auburn Cable, it was swiftly abandoned by 1902 as the grades were too steep for electric cars. The last cable road was the

Vine Street Cable Railway which opened in 1887 and operated between Fountain Square and Corryville. This one was converted to electricity in 1898.

A Crop Flourishes in the City

|

A second-generation Cincinnati Street Railway logo, showing off a motorbus

and a native Cincinnati Car Company double-truck car.

(Cincy Shirts) |

|

An early electric streetcar of the Walnut Hill

Cable Railroad, 1890s. Note the "ring" guards

around the bottom of the streetcars.

(Jeffrey B. Jakucyk) |

Cable cars could only get a city so far, and unfortunately the amount of infrastructure needing constant maintenance told the CSR that there had to be a more prudent solution. Steam dummies were trialed between 1860 and 1872. While they could handle the steep grades, the service was never really popular. CSR's solution finally came in 1888, when George Kerper's

Mt. Adams & Eden Park Inclined Railway strung up some wire on McMillan Street between Gilbert Avenue and Oak/Reading. An extension out to the nearby Baltimore & Ohio station proved fruitful, and soon the first full electric route, the Madison Avenue Line, opened in 1890. Unusually, Cincinnati's electric railways used two wires rather than one, due to the horsecar lines not electrically bonded and thus unable to carry the return current. This issue of rail returns was so contentious that the local telephone company sued the

Inclined Plane Railway Company (who owned the Mt. Auburn Incline) when they tried to build a ground return, citing "current leakage" causing static in their phone lines. After this trial, many electric conversions simply followed suit and copied the cheaper double-wire setup, rather than upgrade the rails. The only other American system to use this widely was the Merrill Street Railway in Wisconsin.

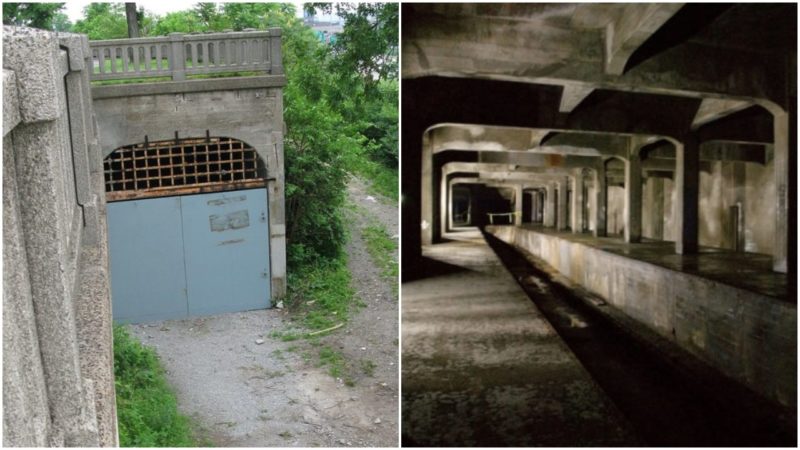

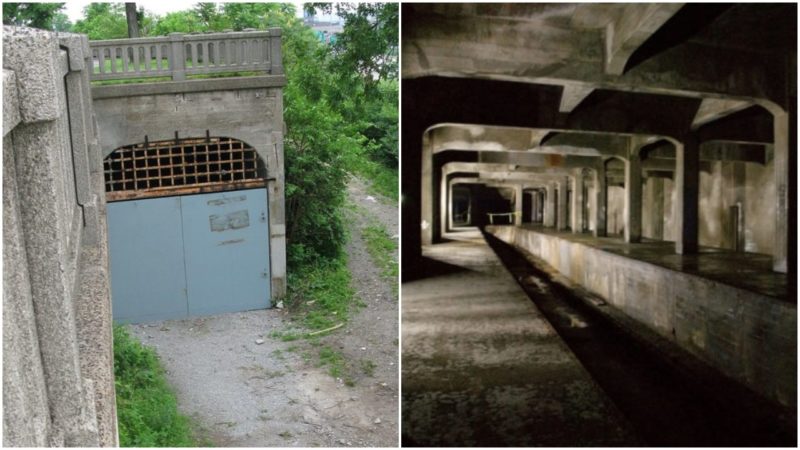

The Cincinnati Subway

|

The Cincinnati Subway under construction, at Findlay Street in 1921.

(University of Cincinnati)

|

|

A map of the 222-mile Cincinnati Street Railway

(Or Cincinnati Traction Company) at its peak

in the 1920s, with a small system into Kentucky.

(WCPO Cincinnati) |

Street railway development into the 1900s was rather small for the Queen City, as the system had built out enough to cover most of the city. Interurban development was quite rapid, by comparison, as companies such as the Cincinnati & Lake Erie sprouted up to meet passenger demands. The last new route on the system, in conjunction with new double-truck streetcars to replace the older single-truck horsecars and trailers, was the three Norwood branches with more lines going out to College Hill, Madisonville, and Cheviot. By the 1920s, Cincinnati's street track was more than 220 miles long, spread across 52 individual lines (though not always chronologically numbered). At the same time, the venerable Miami & Erie Canal fell out of use and the CSR decided this would be the site of their new "subway". Running two miles between Fountain Square and St. Bernard, the subway followed the canal bed for quite a bit as it zigged and zagged in and out of tunnels and surface running. Effectively, this would give the interurban lines a wide berth into Cincinnati (but they were all busy squabbling about what gauge to use to access the city center so they didn't matter). Unfortunately, despite overwhelming city approval and enough bonds to cover the costs of construction, by the time the subway opened in 1925, most of the surface level interurban companies were gone and under new city leadership, and the subway was quietly let go. Remnants of it still remain, unused or repurposed, underneath Cincinnati.

|

Surely this counts as one of those new-fangled "liminal spaces",

doesn't it? Definitely looks like a doorway to another world.

(Abandoned Spaces) |

The Ultimate In-House Designer

|

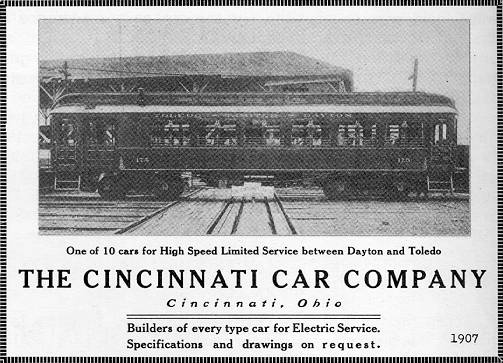

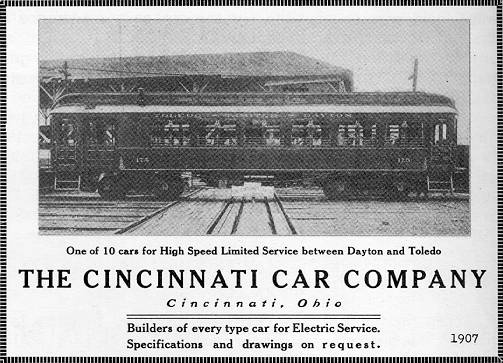

A 1907 advertisement for the Cincinnati Car Company, showing off

a new interurban car for the Dayton & Toledo Railroad.

(Mid-Continent Railway Museum) |

|

Car 2258, built by Cincinnati in 1919, glides past

Oakley Square in the late 1940s.

(Jeffrey B. Jakucyk) |

Uniquely, the CSR was one of the few streetcars with its own homebrew streetcar builder. Founded in 1902, the

Cincinnati Car Company (CCCo) began at the CSR's Chester Park shops and built many cars for their parent company, especially their first single-end, double-truck designs that lasted all the way to the railway's closure. Other Ohio-area railways began asking for their services too, and soon Cincinnati Car grew from just building local streetcars to building "high speed" interurban cars in

Chicago and

Milwaukee. By the 1920s, the company was most well known for building strong, lightweight interurban high speed cars with a pronounced "S"-curve in the side panels that gave them the nickname "Rubber Stamp" cars. They capitalized on this in 1929 when the introduction of the "Red Devil"

high speed cars on the

Cincinnati and Lake Erie, which were only 20 tons and could reach speeds of 90 miles an hour. Unfortunately, the high speed cars could not save the company, as carbuilding ceased shortly after and the CCCo was liquidated in 1938.

|

CSR No. 1128, a rare "Brilliner" that never really caught on

unlike the St. Louis and Pullman PCCs.

(Columbus Metropolitan Library) |

While the CCCo was busy (and eventually controlling the

Ohio Traction Company, parent of the CSR, as well as the

Versare Car Company), the humble street railway also had some other non-CCCo designs. The most prolific of these were the 52 PCC cars built between 1939 and 1947 by St. Louis Car Company. CSR was an early buyer of the PCC design and theirs were the only PCCs to run on double wires. One exception, No. 1128, was the rare "Brilliner" streamlined streetcar that was trialed alongside a

Pullman PCC in 1938, but both were dropped in favor of St. Louis Car. Unfortunately, these cars were not enough to save a now-flailing streetcar system and, following the CSR's closure, most of these PCCs were sold north of the lakes to the Toronto Transit Commission where they enjoyed a long, fruitful working life.

A Streetcar Named "Betrayal"

|

Strange bedfellows at the Brighton Car Barn in 1948.

Car 139 is a 1928 Peter Witt by Cincinnati Car Co,

trolley bus 552 was built by Pullman.

(Mike Morant) |

World War II may have been able to save Cincinnati's streetcars due to gas and rubber rationing, but by the time the war was over, conversion to trolleybuses came quick and fast. This was due to the streetcars being thought of as a complete nuisance, running down the center of the roads and blocking traffic. The citizens, once ardent supporters of the streetcar, now turned against it and even the city government became vehemently anti-rail. The Mount Adams Incline, now just a tourist attraction for the city, closed as routine maintenance was being done on it in 1948 after it was found to be dangerously decayed. Further, private automobile use was on the rise and this meant many, many traffic accidents occurred. By 1950, all but a few railway lines were converted to buses.

|

One week before the end of streetcar service,

PCC 1127 poses next to "Standard" car No. 154 as

then-new Trolley Bus 1508 sidles up behind.

The PCC is on an ERA Special Excursion, one of many.

(Metro Bus Cincinnati) |

The last streetcars operated until April 29, 1951, when the 21-Westwood-Cheviot and 55-Vine-Clifton lines were converted to trolley buses. Around the same time Cincinnati was getting rid of its streetcars, street railway preservation was taking hold in San Francisco as the historic cable cars were saved as a popular tourist attraction. Cincinnati has since been criticized about being unable to realize the value of a historic streetcar system. Development outside the downtown basin was increasingly stunted, and unfortunately buses could not hold a candle to the streetcars as many Cincinnatians moved to the suburbs and continued buying cars. Ridership on buses, indeed, crashed harder than the streetcars as it dropped from 130 million in 1946 to 15 million in 2018. It's safe to say that, after deeming the streetcar a "menace", the Queen City continues to treat the streetcar with disdain

|

Cincinnati "Standard" Car No. 2227 now runs free at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum in Washington, PA.

The car is converted to run on a single pole, and the clerestory number boards are rather interesting.

(Acroterion) |

|

CSR 2435 on display at Cincinnati Union Terminal, with paper trucks.

(Railguy365) |

Today, only four original cars carry the legacy of the CSR. The only operating, and fully restored one, one is CSR No. 2227, built in 1919 by the Cincinnati Car Company. The car was originally saved by the Southern Ohio Division of the Electric Railroaders Association in 1951, shortly after the CSR closed, and now finds its home at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum in 2009. Another car, lightweight No. 2105, was built in 1917 by Cincinnati and has been in storage at the Seashore Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport Maine, since 1993. Another body, "Rubber Stamp" car No. 2435, has its body preserved, restored, and on display at Cincinnati Union Terminal, thanks to the efforts of the Cincinnati Historical Society. The final car, similar "Rubber Stamp" 2465, is preserved in Marietta, Georgia, where the car was sold to after the CSR closed. In all, two restored bodies, one complete car, and a body in storage.

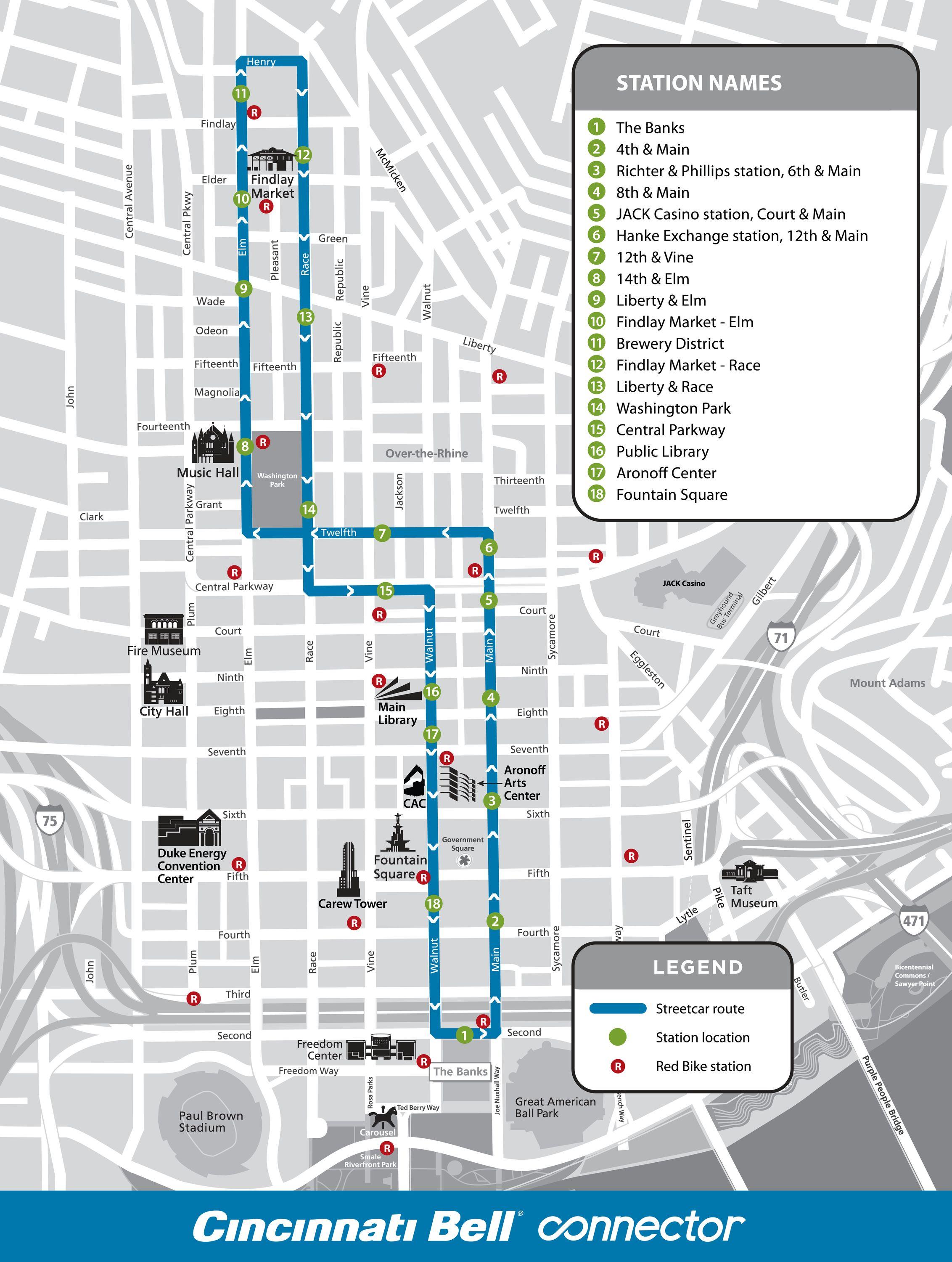

Did They Bring the Streetcars Back? SORTA

|

The street railway lives on.

(WVXU) |

|

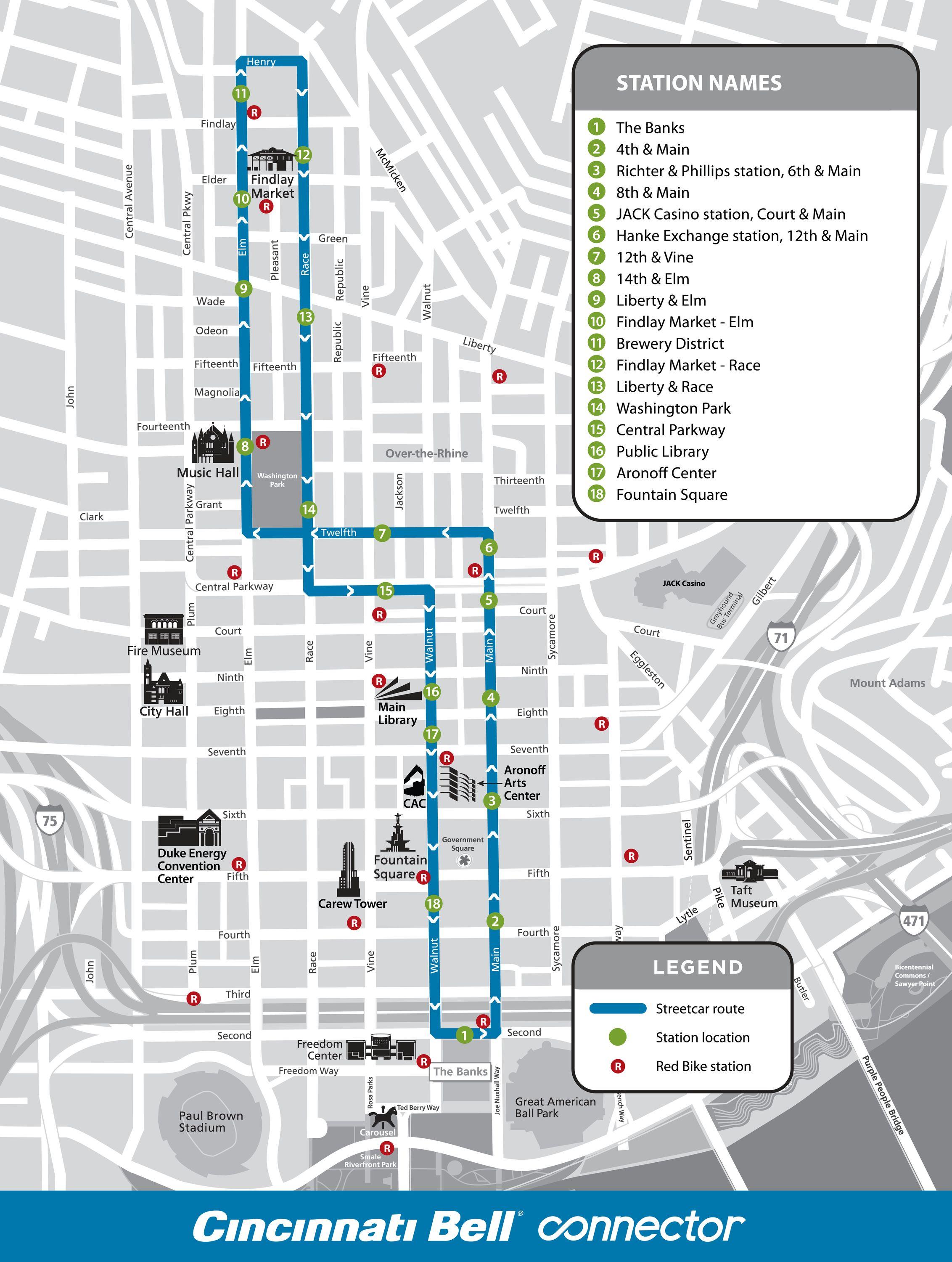

A map of the Cincinnati Bell Connector route.

(WVXU) |

Despite the city's aggressive indifference (and hostility) to streetcars, or any kind of public transit, a new streetcar opened on September 9, 2016, after much development and controversy. The Cincinnati Bell Connector, originally the Cincinnati Streetcar, was developed with "streetcar gentrification" in mind, meaning that any new public transit initiative would surely avert urban decay and bring new development (and dollars) to the area. The development of the Bell Connector was not easy, as the city voted twice on referendums introduced by the Coalition Opposed to Additional Spending and Taxes (COAST) designed to stop the project and future rail projects around Cincinnati, but by some miracle the public voted for it instead. The Bell Connector has also found significant opposition from the Cincinnati City Council, Mayor John Cranley, and Governor of Ohio John Kasich, yet it still opened. The line currently runs on a figure-eight route 3.6 miles long between the Brewery District and the Banks, with a crossover at 12th and Vine, under the

Southern Ohio Rapid Transit Authority (SORTA). Cincinnati Bell, the local phone company, subsidises the operation by sponsoring it. The equipment used are five CAF Urbos-3 flexible light rail vehicles, and unlike the old CSR, the route uses a single 750V DC wire and a standard gauge. It's hopeful that, one day, the line is able to extend further (if not for Gov. Kasich pulling the funding for the Uptown Extension at the last minute). Such is Cincinnati, the town that made a menace out of a public good.

-----

Watch your step as you alight onto the platform and thank you for reading with us! Local sources for this article included Jeffrey B. Jakucyk's

thorough article on the CSR, The Mid-Continent Railway Museum's

article on the Cincinnati Car Company, and the Cincinnati Enquirer's

article on how anti-rail the city has gotten. If you would like to learn more about the museums mentioned here, follow the museum links for the

Seashore Trolley Museum, the

Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, and the

Cincinnati Historical Society. Next week, we complete our C-tour of Ohio by dropping off in Cleveland! Until then you can follow

myself or

my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe

buy a shirt as well! Ride safely, now

!

No comments:

Post a Comment