Bienvenidos, amigos, to another month of streetcar history from us at Twice-Weekly Trolley History! As previously announced, this month will be covering streetcar history all over Central and South America, with some rather interesting familiar faces along the way. First on our "South of the Border" tour is Mexico City, the national seat of government and one of the oldest cities in Mexico, all built on what was once Lake Texcoco and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlàn. As well as being one of the country's largest cities, Mexico City was also once home to one of the largest and most storied streetcar networks in the country. On today's Trolley Tuesday, let's look back on the oft-forgotten but never-gone history of the Servicio de Transportes Eléctricos and its predecessors!

If at First You Don't Succeed, Try, Try, and Try a Texan

|

The first Mexican railway line between Mexico City and Veracruz in 1877.

(H.C.R. Becher) |

|

A steam locomotive of the Ferro-Carriles de Centràl Mèxico

at a normal country station stop, circa 1880s-1897.

(Public Domain) |

Mexico City holds a major place in the country's railroad history, as well as national history, by being the site of many firsts. On July 4, 1857, the first steam railroad in the country connected Mexico City with the port of Veracruz, enabling goods and passengers to move about the country and grow out both cities. It is thanks to this new commercial growth that the Mexico City council saw fit to legislate and award franchises to anyone that could build them a world-class horsecar line for a growing world-class city. Three franchises were awarded over the span of twelve years, in 1840, 1849, and 1852; yet of those three lucrative franchises, nothing ever came of them. These are just my own guesses, but it could have ranged from companies unable to draw up investment capital to break ground or overpromising hucksters who never got any support from a city of about 8 million people at the time. Nevertheless, by the middle of the 1850s, Mexico City needed a streetcar line and their needs were soon answered by an unlikely source.

|

An 1870 engraving shows two horsecars past the bull ring

on Calle Rosales. The cars were built by Eaton Gilbert & Co.

of Troy, New York.

(Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico City) |

On August 13, 1856, the city granted a concession to a Texan named George Louis Hammekin (unknown-1881). Hammekin bounced back and forth between Mexico, Texas, and New Orleans, setting up new industries, wharfs, and warehouses on both sides of the border. While in Mexico City, Hammekin was given the task to build the

Ferro-Carril de Tacubaya (FCT) on a route which ran from the

Plaza de Constituciòn (popularly known as the Zòcalo), west to Plaza de Toros, and then down to Tacubaya. This 8-mile route took a total of two years to build as Hammekin secured capital, infrastructure, and rolling stock from the United States. The line eventually opened on January 1, 1858 (with some disagreement between authors of the actual date, whether it opened in 1857 or 1858 is unclear). Hammekin's streetcars were so novel in Mexico at the time that there was no word yet to describe them like "tranvìa" ("trolley car") so the horsecars were simply lumped together with trains, being described as "trenes". Uniquely among other street railways I have researched, the FCT also employed a "New Regulation" that had first-class cars and second-class cars, at a time when all other street railways had yet to employ parlor cars.

|

A May 30, 1860, streetcar schedule for the Ferro-Carril de Tacubaya, with a "Nuevo Arreglo"

("new regulation" for 1st and 2nd class cars. Operating hours fares are also shown

with fares in reals (until 1897).

(Electra Magazine) |

Competition con Caballo

|

A map of Mexico City's tramways by 1932.

(Allen Morrison) |

|

The only known photograph of Mexican horsecars in this period,

with two cars seen at a corner of the Zòcalo.

(Hector Lara Hernàndez) |

The opening of the FCT opened the floodgates for competitors to pop up in its wake, both traveling to Tacubaya or tracing their own route from the Zòcalo. In 1878, the

Empresa de los Ferrocarriles del Distrito Federal (EFDF) was the largest street railway formed as it ran what could best be described as interurban routes between nearby communities of Tlalpan to the south. Pretty soon, the FCT was being crowded out of its direct line to Tacubaya, as the 3 foot narrow-gauge

Empresa de Tranvìas con Correspondencia (ETC) and the

Ferrocarril del Valle (FV) built competing grids that went up against the existing standard gauge horsecars. By the 1890s, there were well over 124 miles of track running in and around Mexico City's historic center, with 3,000 miles and 55 steam locomotives (for heavier trolley car drags) employed, and eventually one company rose to rule them all: the

Compañìa de Ferrocarriles del Distrito Federal (CFDF, formerly the EFDF). After absorbing all independent streetcar lines by 1882, the CFDF standardized the gauges to the wider standard gauge and began looking for alternatives to their mules and steam locomotives, especially with the invention of electrified streetcars after 1887.

|

The last mule-driven horsecars were not retired until November 24 1932, when

service ended on the Granada Line. Hundreds followed the "funeral procession".

(Electra Magazine) |

Lighting Strikes the Zòcalo

|

The "floatilla" of the first electric cars in Mexico make

their way down the street, with Canadian engineer A.E. Worswick

controlling the lead car, January 15, 1900.

(Allen Morrison) |

Despite the invention and successful implementation of

Frank J. Sprague's electric streetcar in 1887, Mexico City's electric streetcars began with a most inauspicious start. Between 1896 and 1900, Alejandro Escandon (governor of the Federal District of Mexico) operated a battery-powered streetcar running around the Hacienda de la Condesa in Tacubaya. Despite no pictures or other information of this line existing, it remained a novel wonder in the city and an otherwise odd chapter in their street railway history. On April 14, 1896, the CFDF was able to successfully petition the government to follow through with the other electric railways popping up around Mexico (starting with the

Nuevo Laredo railway in the north) and convert from horsecar to electrics. To finance this rebuilding, a group of Canadian and European investors banded together to form the

Mexico Electric Tramways Company (MET) in London, England, and officially purchased the CFDF by August 1898. Under their local name, the

Tranvìas Elèctricos de Mèxico, the MET was set up to own the electrical infrastructure and operate the lines, while the CFDF remained a subsidiary to buy and own the cars (much like how the SP

East Bay Electrics in Oakland, California, USA, retained the name "Central Pacific" as a rolling stock holding company).

|

Rolling stock was used and reused throughout the MET ownership and beyond, as little Brill No. 14

here is seen towing an old horsecar past Chapultepec Park, wearing the "CFDF" insignia.

(Allen Morrison) |

|

A cartoon from an unknown Mexican newspaper abhors the streetcars.

The caption reads: "Finally we have electric trams, yes sir. Nothing like

it has been seen before and everybody loves them!

(Allen Morrison) |

Of course, once the new electric streetcars arrived from J.G. Brill in 1899 and began operating on January 15, 1900, not everyone was pleased (or welcoming) of the much faster, more powerful rolling stock. Popular sentiments told of people being exploded by high-speed streetcars, crushed under their wheels or fried by electric wires, or being shocked by the new high-tension, 600V DC wire. Nevertheless, dignitaries such as the ministers of Mexico, Japan, and Russia attended the first floatilla from the Indianilla carhouse to Tacubaya, tracing the original route of the FCT some 42 years earlier. The MET was also hard at work opening new lines, almost once a month, to places like Villa De Guadalupe and Peralvillo in the North, Mixcoac in the southwest, and of course Tlalpan. By the end of the year, MET had added another 60 miles of electrified track to Mexico City. There was even a funeral service started by the CFDF but continued by the MET, with 28

funeral streetcars in service by the turn of the century. Prices ranged from a humble horsecar of $3 ($94.59 in 2020 dollars) to self-propelled electric cars that cost up to $40 ($1,261.26 in 2020). In March 1906, a group of Canadian investors organized the

Mexico Tramways Company (MTC) and acquired a 75% controlling interest in the MET, incurring a name and ownership change. The local identity remained untouched.

A Street Railway Revolucíon!

|

Little Brill No. 48 cruises through the streets of Mexico City.

(Allen Morrison) |

As the MET advanced into the 20th Century, it very much became the world-class street railway it had promised to be. By the middle of the 1900s, it had established parlor car and sightseeing routes between the Zòcalo to San Anghel, Coyoacàn, and Tlalpan. After 1907, the MTC stopped importing passenger cars from the US and began rebuilding and building their own at their Indianilla shops as a cost-saving measure and to get rid of most of their antique fleet. In 1909, MTC began looking out of the limits of Mexico City as they surveyed two interurban lines to further expand their transport reach. One ran 91 miles across the mountains between Huipulco, on the city's southernmost borders, to Puebla, going around what is now the

Parque Nacional Iztaccìhuatl-Popocatèpetl. The other was a shorter line of 56 miles from Tacubaya west to Toluca, México's state capital. Both lines had their "soft" openings a short time later, as the first 4 miles between Huipulco and Xochimilco were inaugurated on July 12, 1910, while the first 11 miles of the Tacubaya-Toluca line opened as far as La Venta opened in 1912. The latter coincided with a near-7 mile extension of the Pubela line past Xochimilco east to Tulyehualco.

|

A two-car train is seen rumbling down the line along La Viga Canal to Ixtacalco, 1908.

This area is now home to Eje 2 Oriente, a modern 6-lane highway.

(Allen Morrison) |

|

Mexico City's citizens are overjoyed as Francisco Madero takes to power in 1911.

Please do not try this at home, I do not know how those guys are touching the trolley pole.

(Allen Morrison) |

Despite the immense leaps both interurban lines were taking, they were soon halted in 1912 by the ever-growing Mexican Revolution, which started on November 20, 1910. The Revolution began as a response to the unpopular regime of President Porfirio Dìaz, who had taken control of the country in 1876 and oversaw much of the streetcar development in Mexico during that time. Faced with a succession crisis, the elites and middle class of Mexico struggled for control and Dìaz's successor, Francisco Madero, was jailed until Dìaz resigned and went into exile. As Madero took power, and the Zapatistas began rebelling over his new government, so too did Mexico City's streetcar workers with a general strike against insufficient pay and poor working conditions from their company management. Madero resigned in February 1913 in a military coup-d'etat and was immediately murdered and after another bloody phase under General Victoriano Huerta, the Constitutionalist Army took control of Mexico City. Led by Venustiano Carranza, his control was sweeping all over the city as well as the state, with the streetcars being seized by the government against the workers and the MTC, whose stock plummeted for the next 30 years. Streetcar service remained dormant until 1915, when Carranza defeated the army of former ally Pancho Villa, but the MTC remained out of the picture until 1920.

|

A normal scene at El Zòcalo in 1919, following the Mexican Revolution.

Many of the cars here are double-truck Brill, St. Louis,

and American Car products. Note the combination streetcar.

(Allen Morrison) |

Under government management between 1915 and 1920, a general strike was threatened to occur on March 28, 1916, organized by the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies, who previously organized a streetcar strike in

San Diego). Demanding a 60% wage increase, strikers threatened to halt all service at 8AM and motormen, fearing violent attacks, protected their cars in the carbarns. A military force led by General Pablo Gonzalez promptly stopped the strike and dispatched troops to guard all essential infrastructure, like electric plants. Under extreme negotiations, IWW agitators were arrested and a promise for increased pay was set aside for the near future. That future came on January 12, 1923, three years after the MTC took back control of their company following government rule. Unlike the previous strike, this one was rather violent, as reports of bloodshed were printed in special cables to the

New York Times (of which I had to take out a subscription for, thank me later). While this strike went nowhere, it further fueled animosity with the MET and its workers, who saw the Canadians as paying them slave wages when that promise from 1916 was never honored.

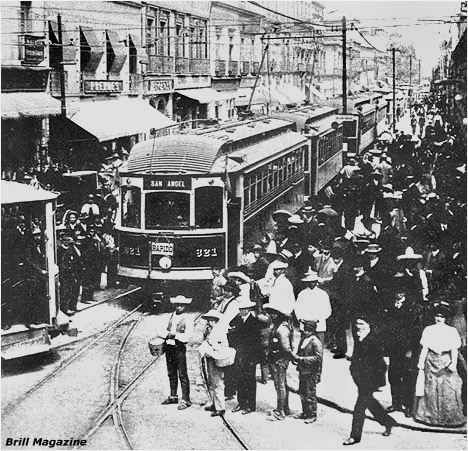

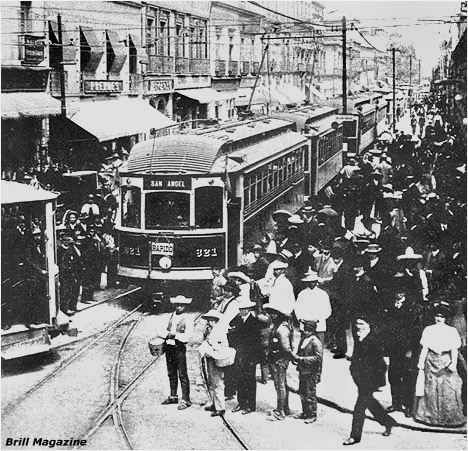

|

In this 1911 scene, the first suburban trains to San Angel

are mobbed by riders as they make their way down the street.

(Brill Magazine) |

Tensions finally flared during the worst possible time: World War II. At the time, the MTC was depended upon by millions of riders as gasoline rationing went into effect, and both the motormen, shophands, and the rolling stock and infrastructure were feeling the strain. The Mexican government at the time was also keeping the MTC under harsh scrutiny, as complaints to the city and the state told of poor service and broken contracts led to intense distrust in privatized public transit. In February of 1945, tensions finally spilled and the MTC's workers finally held a long and sustained strike against their corporate masters. Incensed by the violence at a time like this, the Mexican government stepped in and confiscated the MTC's property and employees under a new municipal agency, the

Servicio de Transportes Urbanos y Suburbanos. After the war, when the strike was quelled, the new agency was reorganized as the

Servicio de Transportes Elèctricos (STE) in 1947. In response to this, the remaining shareholders of the MTC refused to give up their remaining control until January 25, 1952, when the Departamento del Distrito Federal (DDF) purchased he last of the MTC's assets for a cool 14 million pesos.

|

A map of the absolute extent of Mexico city's tramways, showing the interurbans lines out

to La Venta, Xochimilco and Tulyehualco.

(Allen Morrison) |

Notable Streetcars

|

The disastrous double-decker cars which could seat 72

passengers in reasonable comfort, but were stymied by their

inability to take a curve. Most people consider this an essential

feature for any railed vehicle.

(Allen Morrison) |

Over the years that the

Mexico Electric Tramways Company and its successor, the

Servicio de Transportes Elèctricos, operated streetcars in Mexico city, they rostered a variety of American-built and homebuilt streetcars. The majority of these came from the

J.G. Brill Company, who supplied the CFDF with sixty single-truck, open-platform horsecar derivatives beginning in 1899. These cars were often seen towing horsecars for added passenger capacity, and copies of them were later produced by American Car & Foundry and St. Louis Car Company. Around this time, the MEC also rostered double-decker streetcars from Brill beginning in 1901, featuring their much-maligned "Maximum Traction" streetcar truck. These were rather cumbersome creatures for being Mexico's first double-truck streetcars, and while they were loved by the public for their exoticness and breathing room, the MET did not as they were prone to derailing frequently, weighed too much for the system, and one even ended up tipping over on a curve. They were later replaced by much longer open summer cars (resembling the Narragansett cars running in

Lowell, Massachusetts) beginning in 1903, and two more "Metropolitan" cars (same style, but half-open, half-closed) joined the system by 1904.

|

Big, long open-style cars fill the Indianilla Carbarn in 1903.

(Modern Mexico) |

|

The "Anahuac" parlor car, photographed at the Indianilla Carhouse

before entering service. It was later rebuilt as a normal passenger car

and renumbered to "430".

(Luis Leòn Torrealba) |

By 1906, alongside the 26 funerary cars, the now-MTC operated 178 streetcars, 44 trailers, 72 freight motors, and 79 freight trailers, alongside 139 still-in-service horsecars, 7 steam locomotives, 51 funerary horsecars, a hospital car, and a prison car on the parts of the MTC as-yet electrified. Much of these new cars were large interurban-style cars from St. Louis Car Company, which were used on the heavily-trafficked suburban line to San Angel. One of these St. Louis Cars was the "Anahuac", a parlor car that often ran on its own to San Angel and featured arched windows and curtains inside. After the Revolution, the newest cars ordered were six 1918 Birney Cars from American Car, the first to be imported since 1907. By 1925, MTC reported owning 315 passenger motors, 20 horsecar trailers, 82 double-truck streetcar trailers, 29 funerary cars, 27 funeral trailers, and 4 "special cars", presumably officer's cars. Another 50 cars were imported from 1924 to 1927, this time being

Peter Witt cars from Brill that later went to Veracruz. The last new cars ordered by MTC before WWII were 30 double-ended "

double Birneys" from Brill, which arrived on Mexican metals in 1927.

|

This Peter Witt No. 610 may be plastered in beer advertisements, but let's hope the motorman isn't similarly plastered.

(J.W. Higgens) |

|

An 1899 Brill single-truck car was rebuilt with a Birney-esque body and doors on both sides in this 1953 photo.

Note the kid engaging in some railfanning himself.

(J.W. Higgens) |

|

Extremely-modernised No. 544 shows that its normally-rounded roof

is now squared away, and ovoid standee windows have been added to give a

modern flair, despite the grubby condition.

(Earl Clark) |

Following the formation of the STE in 1947, it was clear that the cars were in need of a severe rebuilding. Beginning in the 1950s, the Indianilla shops began working overtime to update cars from the 1900s, giving them more robust fronts and "standee windows" to better suit modern sensibilities. As many of these cars were pushing near-50 years old, mass scrapping was the way of life as parts were cannibalized from older cars to supplement rebuilding only the largest and most robust of the fleet. To accommodate this gap in the roster as cars went down for service, Mexico City purchased 88 "Double Birneys" from the Providence, Rhode Island, streetcar system between 1946 and 1948. By August 17, 1953, the STE seemed to be yearning for PCCs as it rebuilt Car No. 680 (formerly a Peter Witt) into a bolted-together, squared-off PCC facsimile.

|

Oh... oh no.

(Earl Clark) |

|

One-of-a-kind No. 680 in color, showing off its "chlorophyll"

scheme in the 1950s.

(Raymond DeGroote) |

Unlike a PCC, Car No. 680 retained doors on both sides and the oddball set the stage for the first PCCs to arrive in 1954, when it ordered 91 cars second-hand from Minneapolis in 1954, then another 183 from Detroit the next year. Due to their yellow color, they were known as "clorofilos", or "chlorophylls", which set them apart from the grimy city streets they served. Up to 1957, the PCCs worked alongside older double-truck cars that MTC had rebuilt several times over; however, after the closure of the Indianilla shops, these cars were sent for scrap and the PCCs remained the only cars working in Mexico City alongside the trolley buses at the new Tetepilco carhous. Those still working saw various lines extended or closed until the only lines left were the Xochimilco line (which got double-tracked in 1960) and the Tlalpan line branching off at Huipulco. Recognizing the days of the PCCs were numbered as the newer Metro was built, the STE resurrected a portion of the Valle line as the "

Circuito Històrico" alongside original Brill Car No. 0 in December 1971. This lasted until everything, including the heritage trolley line, was finally abandoned in 1979, leaving only trolley buses in their wake.

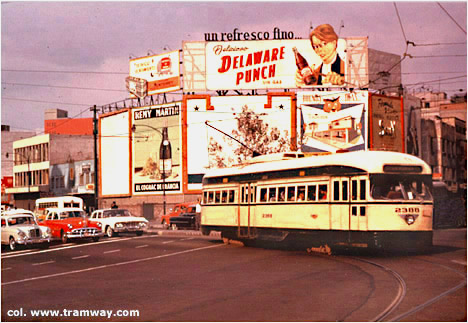

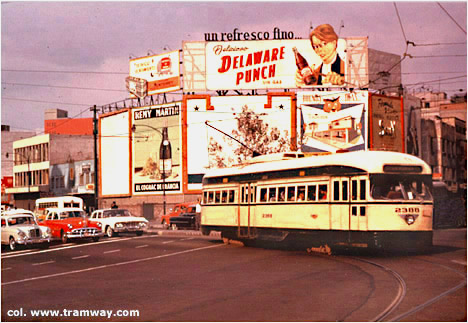

|

Ex-Minneapolis PCC No. 2388 take the curve on the Obregòn line on March 24, 1954.

(www.tramway.com) |

|

Rebuilt Ex-Detroit PCC Car No. 2156 is seen here with cut-in central platform access doors

and a new livery in 1978, being harried by two Volkswagen Beetles from nearby Puebla.

(Allen Morrison) |

Decline of the Streetcar Empire

|

The aftermath of the 1953 Mexico City streetcar disaster.

(Associated Press) |

So how did Mexico City's streetcars fall so hard, despite municipal control? Well, it all started with a bang, unfortunately. On February 1, 1953, two streetcars (Suburban Cars Nos. 800 and 801) collided at high speed on a curve on the La Venta line, another heavily-trafficked suburban corridor. One car (it is unsure which) lost its brakes while descending down a grade and struck the opposite car, guaranteeing a catastrophic head-on collision. Due to the wood construction of the cars, which were built by St. Louis Car in 1906, it was guaranteed that nothing was left in the wake of the accident. Sixty-three people died and thousands more living within Mexico City were horrified and more distrustful of their street railway, which nearly led the STE to go under as it closed the La Venta, Belen, Coyoacàn, Ixtapalapa, Lerdo, and Tizapàn lines all within months of each other through 1953. Traumatised by the wreck and the intense closures, STE management went into the 1960s wondering what to do about its now-dangerous and anachronistic streetcar lines.

|

True anachronism, as 1907 St. Louis Car No. 841 (rebuilt many times over) is seen here operating a

two-car Xochimilco service in 1953, still looking fresh as a daisy.

(William Janssen) |

|

History meets history as ex-Minneapolis Car 2248 meets "Cerito"

on the Valle heritage streetcar line during the 1970s.

(Allen Morrison) |

The response to this was not only through new trolley buses, but also the creation of the Mexico City Metro (MCM) which opened in 1969. The new subway system opened to replace the streetcar line on Avenida Chapultepec and was seen as a much safer, faster way to get around the city. In 1970, the second line of the MCM opened to replace the Xochimilco streetcar's northern end between Tasqueña and the Mexico City border. Even worse, new "ejes viajes" ("travel axes") were being constructed through Mexico City and its outlying areas, bringing the convenience of freeway and main street corridors through the much-unchanged urban landscape. These corridors also brought with it more consideration for trolley buses to access much of the city, cutting off the streetcars more and more until by 1976, the network only consisted of three lines (Xochimilco, Tlalpan, and the Valle Line heritage car) spanning about 97 miles in total. In 1984, the Tasqueña-Xochimilco streetcar became the last trolley to operate in Mexico City, ending 128 violent, eventful, and expansive years of the city's streetcars, with the only survivor being little old No. 0 or "Cerito", which is now in the Tetepilco STE Museo. For the next two years, there was nothing else like it.

|

Little "Cerito" at the Tetepilco STE Museo, preserved and under shelter after last operating in 1990.

(France N. Roseau) |

Except for an earthquake.

From Trolley to Light Rail

|

PCC-rebuild NO. 025 is seen at Huipilco Junction in 1995,

retracing the original line on the Xochipilco Light Rail.

(Thomas E. Fischer) |

In the wake of the violent 1985 Mexico City earthquake, many PCC cars stored at Tetepilco were destroyed, along with much of the original Xochimilco line's tracks. However, as early as September 1984, the STE were already planning to upgrade the line to modern light rail to better match Mexico's aim to be a global city-state. The existing line between Tasqueña and Xochimilco began a period of rebuilding in the wake of the earthquake, with new grade-separation, semi-enclosed stations with high-level platforms, concrete tracks, and new overhead catenaries. Even the rolling stock was developed so closely with local contractor Moyada, as parts like trucks and motors were taken from the destroyed PCCs and reused on the modern LRV cars. The first leg, between Tasqueña and Estadio Azteca, opened on August 1, 1986, and operated for a few days until the LRVs broke down due to poor reliability. After rebuilding, service resumed in November 1986, and the second half to Xochimilco opened on November 29, 1988. It still runs today between its two terminals, now using more purpose-built Bombardier and Concarril cars delivered between 1990 and 2014. In 2008, the original Xochimilco station (named "Embarcadero") was moved 200 meters closer to Xochimilco, due to the new location being closer to the town's center and following closely following the older tracks.

Thank you for reading today's Trolley post, and watch your step as you alight on the platform. My resources today included Allen Morrison's report on the complete history of

the Tramways of Mexico City and its bibliography, two New York Times articles about

two Mexico City streetcar strikes, and the photo credits under each caption. The trolley gifs in our posts are made by myself and can be found under

“Motorman Reymond’s Railroad Gif Carhouse”. On Thursday, we skirt the Gulf of Mexico as we look at the ex-Pacific Electric cars of Veracruz! For now, you can follow

myself or

my editor on Twitter, buy a shirt or sticker from

our Redbubble stand, or purchase my editor's self-developed

board game! It's like Ticket to Ride, but cooler! (and you get to support him through it!) Until next time, ride safe!

No comments:

Post a Comment