Welcome to a brand-new month of Twice-Weekly Trolley History content that we are dubbing "SEPTAmber". From now till the end of the month, we'll be looking at the wide, varied, and ongoing streetcar and interurban history of the state of Pennsylvania, from the ever-large Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority and its constituent companies, to smaller operations like the Johnstown Traction Company, the Pittsburgh Railways, and an electric railway in Reading guaranteed "unsinkable". Today, we'll be looking at the City of Brotherly Love's rocky history as the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, and all the trials and tribulations it endured until it was reorganized at the eve of World War II. Let's jump into it!

-----

A City of Upstarts and Experiments

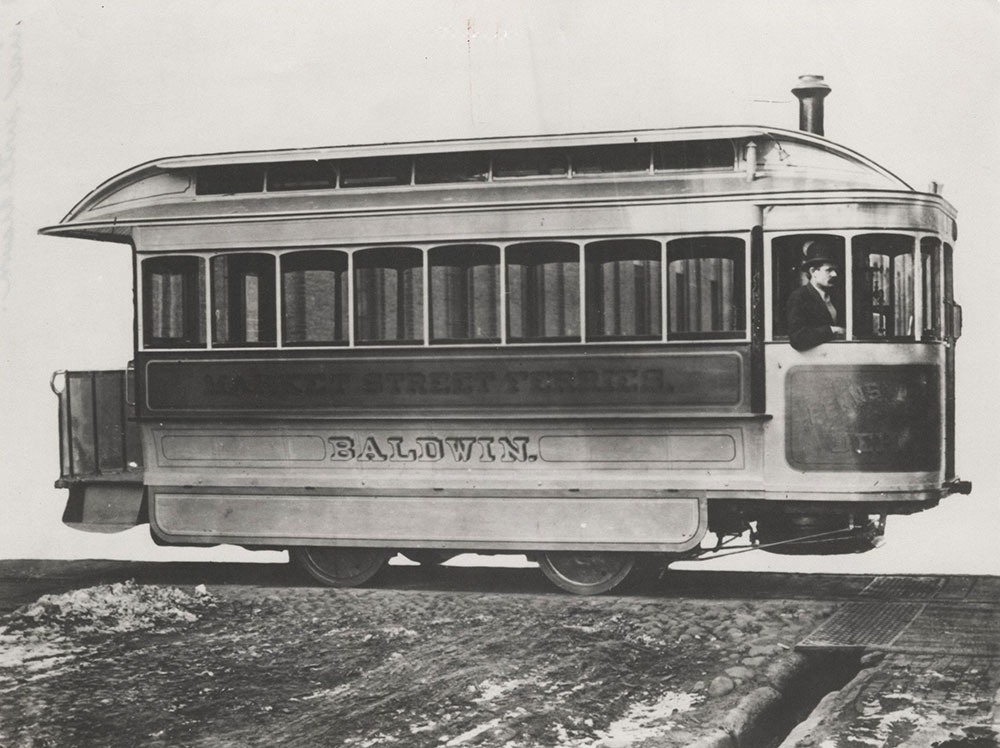

| A line of horsecars belonging to the People's Passenger Railway Company wait for eager commuters somewhere in the mid-1800s. (Philadelphia Trolley Tracks) |

|

| Horse Car No. 5, in this Brill company photo, belongs to the Fairmount Park & Zoological Gardens Railroad. (Free Library of Philadelphia) |

Like almost ever street railway founded before the 1890s, Philadelphia's street railway history starts with horsecars. The Philadelphia & Delaware River Railroad began this trend as it was incorporated in 1854, but did not begin operating until 1858. Originally a 50-mile steam railroad heading north to Easton (northeast of Bethlehem and Allentown), the plan changed to a slightly-cheaper 5-mile horsecar line south from Kensington Avenue to Southwark Street and hugging the Delaware River. This company promptly changed its name to the Frankford & Southwark Philadelphia City Passenger Railroad Company (a huge mouthful), and it was soon joined by 66 other street railway lines chartered and franchised up and down Philadelphia between 1854 and 1895. This huge growth in horsecar companies enabled the city to grow outward as more people flooded in for work, and companies started looking towards new means of streetcar propulsion.

![Map of Philadelphia [horse car routes], 1875, Map](https://media.freelibrary.org/assets/digital/items/map00000187/images/large.jpg) |

| A map demonstrating how prolific Philadelphia's street railways were by 1875, with some even extending outside the map! Fairmount Park and the Schuykill River are on the left and the Delaware River is the big bendy watery thing on the right. (Free Library of Philadelphia) |

|

| A Steam Dummy operated by the Fairmount Park- Market Street line, looking both modern and antiquated. (Free Library of Philadelphia) |

|

| An artful brick-arch bridge in the Chamounix area of Fairmount Park that once carried the trolley through on its loop run. (Bradley Maule) |

|

| The Belmont Inclined Plane in 1837, now a passenger cable railway. The angle-roofed car is the "grip" car. (Davis Shaver) |

| A normal two-car train operation (one motor, one trailer) of the Fairmount Park Transit Company, 1946. (A. W. Maginnis) |

Mergers and Modern Problems

|

| A 1920s Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company stock header, showing a double-decker bus flanked by a Market Street Elevated car and a "Peter Witt" streetcar. (Ghosts of Wall Street) |

|

| A small Brill electric streetcar belonging to the Philadelphia Traction Company, the first of its kind. (The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia) |

|

| A contemporary postcard of unknown year of the Market Street Elevated at Fortieth Street Station. The cars are New York "Lo-V" cars supplied by Pressed Steel. (Charlie O'Hay) |

The next year, the PRT leased the newly-franchised Market Street Elevated Passenger Railway Company (or Market Street Elevated, again with these long company names...) as the company had an exciting new prospect in store: an elevated railway from the Delaware River to the western city border. The only problem was the conditions the city imposed upon the PRT to allow its construction: it had to be paid out of the company's pockets and (worst of all) it had to go under the town between the Delaware and Schuykill Rivers. This put PRT into a deep, deep situation as due to the rare stipulation of a city forcing a company's private capital to pay for any major infrastructure (rather than city tax measures or investment programs), the company itself had to foot $23 million dollars ($656 million), when it was already in a shaky financial situation following the big merger. When the first section of the Market Street Elevated (from 69th Street Terminal to the City Hall Loop) opened in 1907, Philadelphians celebrated while City Hall was absolutely furious at how long it took to build the 6.2 mile long line. PRT was left nearly-bankrupted by the venture, and while a new Department of City Transit planned on more subway extensions, the workers were getting restless.

The Philadelphia Streetcar Strikes

|

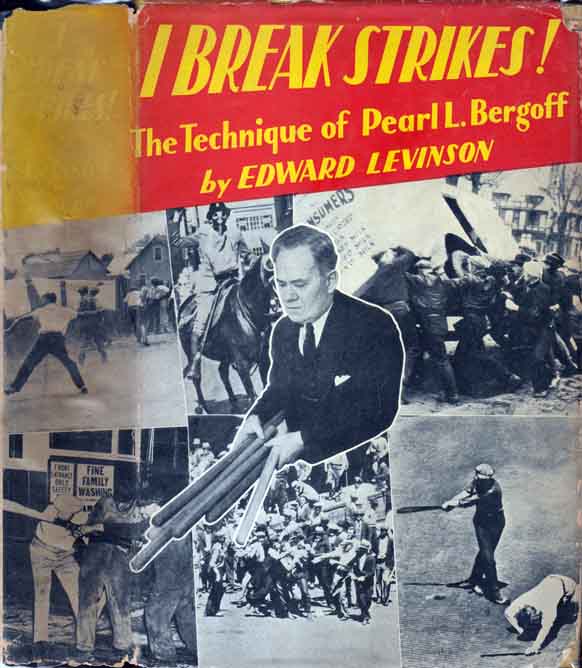

| The cover of a biography of Pearl L Berghoff, published in 1935. (Abe Books) |

Starting on May 29, 1909, the strike began with the Amalgamated Association of Street & Electric Railway Employees of America (AASERE) approached the PRT with a few simple demands: a 25-cent hourly wage ($7.12 in 2020, still very low), uniforms supplied through the open market rather than the company store, 9-10 hour workdays, and recognition of the Union. The PRT refused to meet, instead hiring strikebreaker Pearl Bergoff (the so-called "King of the Strikerbreakers") and numerous scab motormen, conductors, and shopworkers to fill in the void. Violence immediately broke out, with trolley cars and infrastructure destroyed and wholesale arrests and acts of police brutality committed. The PRT already had a negative reputation following the delayed opening of the Market Street Elevated, as well as general dislike for its poor service, so the AASERE felt safe to issue this ultimatum through John J. Murphy of the Central Labor Union:

If the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company does not meet the demands of the trolley workers by Thursday night (June 7), a strike of all organized labor bodies of Philadelphia affiliated with the Central Labor Union, representing 75,000 men, will be called for Friday morning. The present strike is only a beginning of the fight which will be waged by organized labor to emancipate the city of Philadelphia from the thralldom of capitalism.

|

| John J. Murphy, as documented in the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 1, 1910. (Philadelphia Inquierer) |

|

| Strikers meeting at the 16th/Jackson Carbarn in February 21, 1910, the second day of strikes. (Public Domain) |

By December 1909, the AASERE tried again to bargain with the PRT, who again refused to concede. Without further union discussion, the PRT instead put out a new "welfare plan" that was just as complicated as it was actively malicious: wages were kept at a tight 22-cents an hour ($6.26 in 2020) and instead of less working hours, insurance and pension plans were bandied about. After seven workers were fired following their vocal criticism of the PRT's "welfare plan", 5,300 union members voted to strike and charged the transit company with creating "dissention and discord." Unfortunately, the city had turned on the Union too, with the mayor siding with the PRT and saying the workers "owed their service to the city." Even Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) urged the PRT to reach a settlement, but the transit company stubbornly told him they had everything under control. Following the firing of some 173 union workers on February 19, 1910 and hiring more scabs from New York City, the strike of 1910 began.

|

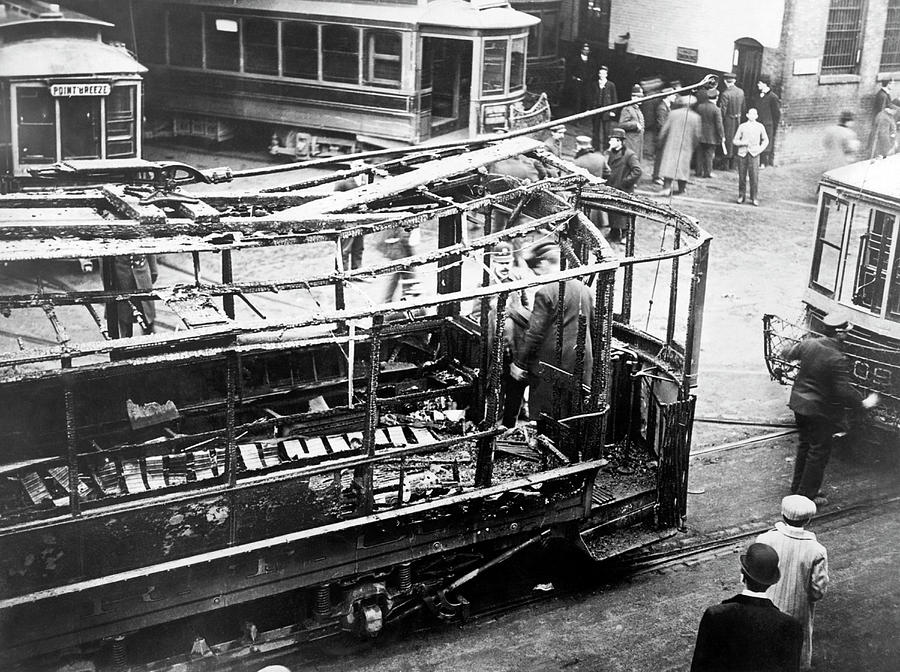

| A double-truck Brill car burned to its frames following striker action, one of many that morning of February 20th. (Underwood Archives) |

Some 6,200 workers of the PRT's 7000 walked out the morning of February 20, 1910, and immediately sabotage was the order of the day. Masonry was torn from school construction sites to block streetcars and lob at strikebreaking officers; a volunteer motorman was reported to have been killed after driving his streetcar through a crowd and waving a revolver, only for the car to get derailed through a "spiked switch". 2,000 strikers, at one point, seized a trolley car and burned it in effigy, while dozens more were burned or dynamited. The mayor enforced the riot act harshly, deputizing 3,000 citizens and denying the AASERE a chance to have their unionized citizens "preserve peace and order". As the strikes continued and city commerce ground to a halt, the unending chaos, public backlash, and solidarity walkouts across the East Coast finally brought the PRT, and Philadelphia's city government, to its knees. In March, the PRT settled with the AASERE and a new PRT president, Thomas A. Mitten, pens a "cooperative plan" guaranteeing increased wages, benefits, and buying clubs for better worker relations. Unfortunately, this settlement also forced the PRT to maintain a 5-cent passenger fare to improve public relations, which severely affected the accounting books for years after.

| Part of the Frankford Elevated's tunnel system in 1916, which touted unballasted track as giving a 50% savings on track maintenance in the Electric Railway Journal. (Electric Railway Journal) |

With the strikes out of the way, the city finally decided to re-focus its efforts on building that big subway east of City Hall and across the Schuykill River. The plan, presented by transit commissioner A. Merritt Taylor in 1913, was for seven new subway and elevated lines all around Philadelphia (including a subway loop at Center City) that would eventually become the "Frankford Elevated". Unfortunately, the election that fall meant a new mayor who rejected Taylor's plan outright; there would be no expensive transit projects under his administration. Unfortunately for Mayor George Connell, the City Council went over his head and put the Frankford Elevated plan into action in 1915, starting with tunnel boring under City Hall. In what can only be called a big "Whoops", the project nearly bankrupted the city by 1917, with City Hall station being finished quickly to avoid the building falling into the giant hole. Without any financial support from the PRT, who was having its own issues recovering from the strikes, the Frankford Elevated opened on November 5, 1922. The city paid $15.6 million dollars for the line ($240 million today), less than the Market Street Subway but twice as long and in more dangerous financial straits.

A Phoenix From the Ashes - 1920s-1940

|

| Thomas A Mitten, proving he can both keep a transit company together and induce soft focus in a camera using only his moustache. (Old Images of Philadelphia) |

As the city was trying to recoup the losses from the Frankford Elevated's construction, the PRT's system now spanned an enormous 696 miles of track, three times what it had been in 1902. The number of daily passengers also increased three-fold, from 344 million in 1902 to 917 million by 1924. However, due to the rigid fare charge cutting deep into the PRT's earnings, it didn't take long for the word "bus" to cross the executive's lips. In 1923, the Philadelphia Rural Transit Company began double-decker bus operations on Roosevelt Boulevard. This led to the PRT experimenting with Brill "trackless trolleys" that same year on the Oregon Avenue line. This was the only trolley bus operating in Philadelphia, but it gave the company hope for cheaper and more efficient operations. However, what upward momentum the PRT had was lost just five years later. On October 1, 1929, Thomas E. Mitten, the man who helped calm PRT's union workers and operate a steady company, was found drowned in an upstate Pennsylvania lake. This tragedy came days after a city lawsuit was filed inquiring about the PRT's finances. What happened next can only be described as a tailspin.

| A Brill Trackless Trolley takes its delivery photo on PRT's Route 80 along Oregon Avenue, October 1923. (Philadelphia Trolley Tracks) |

As the PRT continued normal operations into the 1930s, the company fell into receivership. The Great Depression was not kind to the private entity, and the city knew that in order to stop the company possibly going under, they would have to take municipal control of it. By 1935, the courts decided the company would, astoundingly, remain private despite the immense losses and decreased ridership from years of stagnant fares and expensive extensions like the Broad Street Subway (which had the highest fare on the system at 15 cents, or $2.23 today) were halted due to the war in Europe. After two more years of dithering, the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company ran its last streetcar in December 1939. Come January 1, 1940, the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) took over all operations of street, subway, and elevated lines. And with a new company came, of course, another massive strike.

-----

Thanks for reading this multi-part report on Philadelphia's streetcar history. I know this first part seems rather sour in tone, but sometimes that's just history. I didn't have time to report on the unique cars, so as a treat, I'll make that part two next Tuesday! References for today's report include Philadelphia Trolley Tracks, Davis Shaver's report on the Fairmount Park Railway, and Philadelphia Magazine's timeline of SEPTA's "Prehistory". No museums to plug today, but I'll take any opportunity to plug mine and my editor's twitter pages, as well as our Redbubble store where you can buy stuff with trolleys on it. Until next week, ride safe!

No comments:

Post a Comment