-----

|

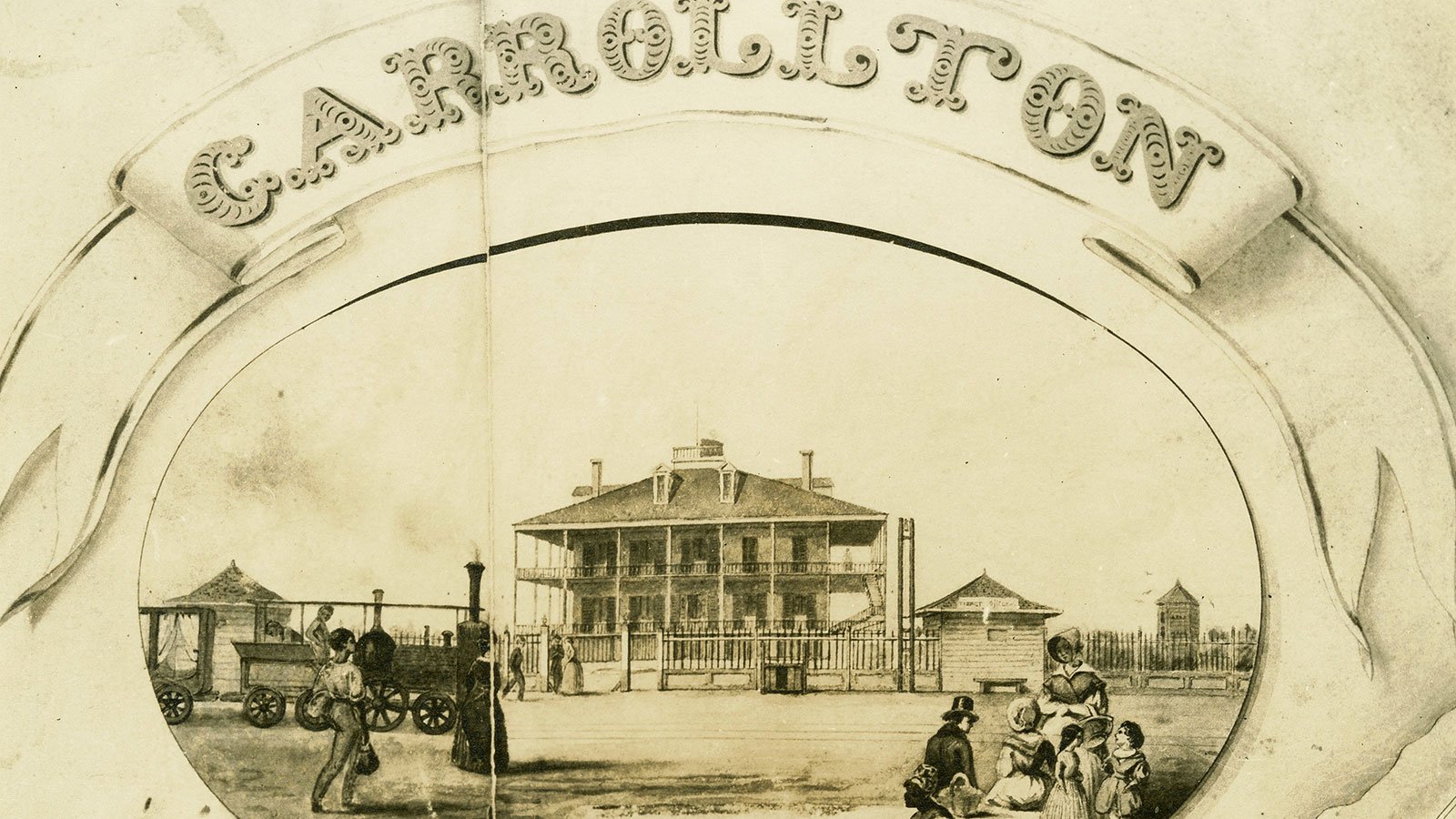

| An artist's rendition of the Carollton Hotel, circa 1830s, with a steam locomotive off to the left. (WTTW) |

|

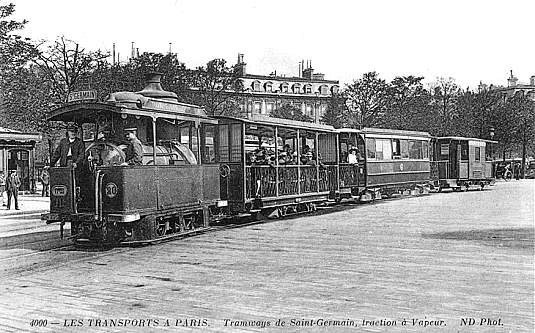

| A later Lamm-designed ammonia fireless tram in use in Paris, France. (TramwayInfo.com) |

|

| The original Carollton Avenue streetcar, in New Orleans & City Railroad lettering, 1890s (Wikimedia) |

|

| A Magazine Street car with crew posing around it at Arabella Carbarn, 1890s. (Public Domain) |

Consolidation began in 1892 the New Orleans Traction Company was formed by combining the New Orleans City and Crescent City Railroads. After renaming itself to the New Orleans City Railroad (NOC) in 1899, it took over all operations in 1902 and finalized its official name by 1905 as the New Orleans Railway & Light Co. (NORLCo). This did not go over well with workers from the constituent companies, especially as NOC (in 1902) upheld already-charted workplace agreements from the constituents while the workers demanded one agreement for the entire company. Division 194 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America was formed immediately and struck on September 27, 1902 for recognition. A settlement was reached in two weeks, but this wasn't the only rocky point for the New Orleans street railways.

|

| A horsecar stands idle on Canal Street, just across from the Henry Clay statue, in the mid-late 1860s. (Public Domain) |

New Orleans has always been known as a city with a heavily-African American population, both noteworthy and nondescript. As was expected in the days before the Civil Rights movement, all public transit was segregated and New Orleans was no different. Here, horsecars designated with a star on the side were for blacks only, dubbed the "star car" system. This did not stop one instance of civil disobedience as in April 1867, two years after the Civil War ended, William Nichols was forced out of a white-only car after boarding. The city's African American population protested following this incident, and the city, wanting to avoid any more violence from its citizens, quickly declared the city streetcar systems desegregated by May 8. The Chief of the Police at the time told his officers:

“Have no interference with negroes riding in cars of any kind. No passenger, has a right to eject any other passenger, no matter what his color.”

This period of desegregation came to an end come 1902, when the state legislature mandated that "public transportation must enforce racial segregation". Both white and black riders found this incredibly inconvenient, while the street railways complained this put unwanted expenses on them to not only invest in more segregated streetcars, but also have their conductors and motorman attempt to determine the racial background of New Orleanians, many of whom had mixed Creole or Cajun ancestry. Racial segregation officially and peacefully ended on New Orleans streetcars in 1958 following the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1956.

|

| A map of the New Orleans streetcar system by 1945 (Transit Maps) |

Operations-wise, the consolidation did well to help trim the fat off some of the city's often-redundant streetcar routings like the Coliseum Line (nicknamed "the Snake"), which wandered through much of uptown New Orleans via Canal, Coliseum, and Upper Magazine streets. All three were split into their own respective street lines for more efficient operations, and most lines following Canal Street were cut off to allow for less congestion. 1920 saw the biggest addition to the system in the form of the famous Desire, Freret, Gentilly (named for the neighborhood, rather than the street it ran on), and St. Claude Lines. These lines opened between 1920 and 1926 and were the first four lines to be added since the Spanish Fort (along Lake Pontchartrain, opened in 1911) and the S. Claiborne (running alongside a "neutral ground" canal, opened in 1915) lines. The only line not indicated as an official service was the Orleans/Kenner Interurban which opened in 1915 between Hanson City (now Kenner) to Rampart and Canal Streets.

|

| Car 947 departs the Carrollton Station carbarn on August 22, 1955, with a GM bus looking on sternly. Note the shop sign above the car. (Charles Howard) |

In 1922, the company renamed itself the New Orleans Public Service Incorporated (NOPSI) and two years later, diesel and trolley buses made their debut in the city. Some of the lines, like the Louisiana, Esplanade, Prytania, North Claiborne, and Spanish Fort, closed in the early 1930s in lieu of diesel bus service, but the whole system was never in danger of any hostile takeover from National City Lines. Despite the entire system being regauged in 1929 to 5'2.5" "Pennsylvania Trolley Gauge", the onslaught buses couldn't be stopped. By the 1950s, only the S. Claiborne, Napoleon, Canal, and St. Charles lines were left. The first two gave way to buses in 1953, while the Canal line was converted in 1964, leaving only the first electric line in New Orleans left in operation.

By the early 1980s, the city realized that, like in Denver, private transit companies were no longer viable as increasing dependence on buses left the companies with no responsibility to maintain the roads, especially with only one streetcar line left. With the aid of the Louisiana Legislature, the New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) was formed in 1979 with the intention of maintaining and operating the city's public transit with tax money and federal funding. With this came the possibility of having the St. Charles Streetcar (now the oldest continually operating streetcar line in the world, since 1835) be joined by other reconstructed lines, but that's a story for another time...

|

| Canal Street Line, 1955. (John Smatlak) |

-----

Bonjour et merci beaucoup for reading today's Trolley Tuesday post! On Thursday, we take a look at our first report dedicated to a single car works (that being the Perley A. Thomas carworks) and its various products fitted for the New Orleans street railways, then we look at the modern RTA next Tuesday! As always, you can follow myself or my editor on twitter if you wanna support us, and maybe buy a shirt as well! Remember, I have "Trolley Pride" shirts available for a limited time this month! Ride safe!

That's a lovely writeup good luck

ReplyDelete