-----

|

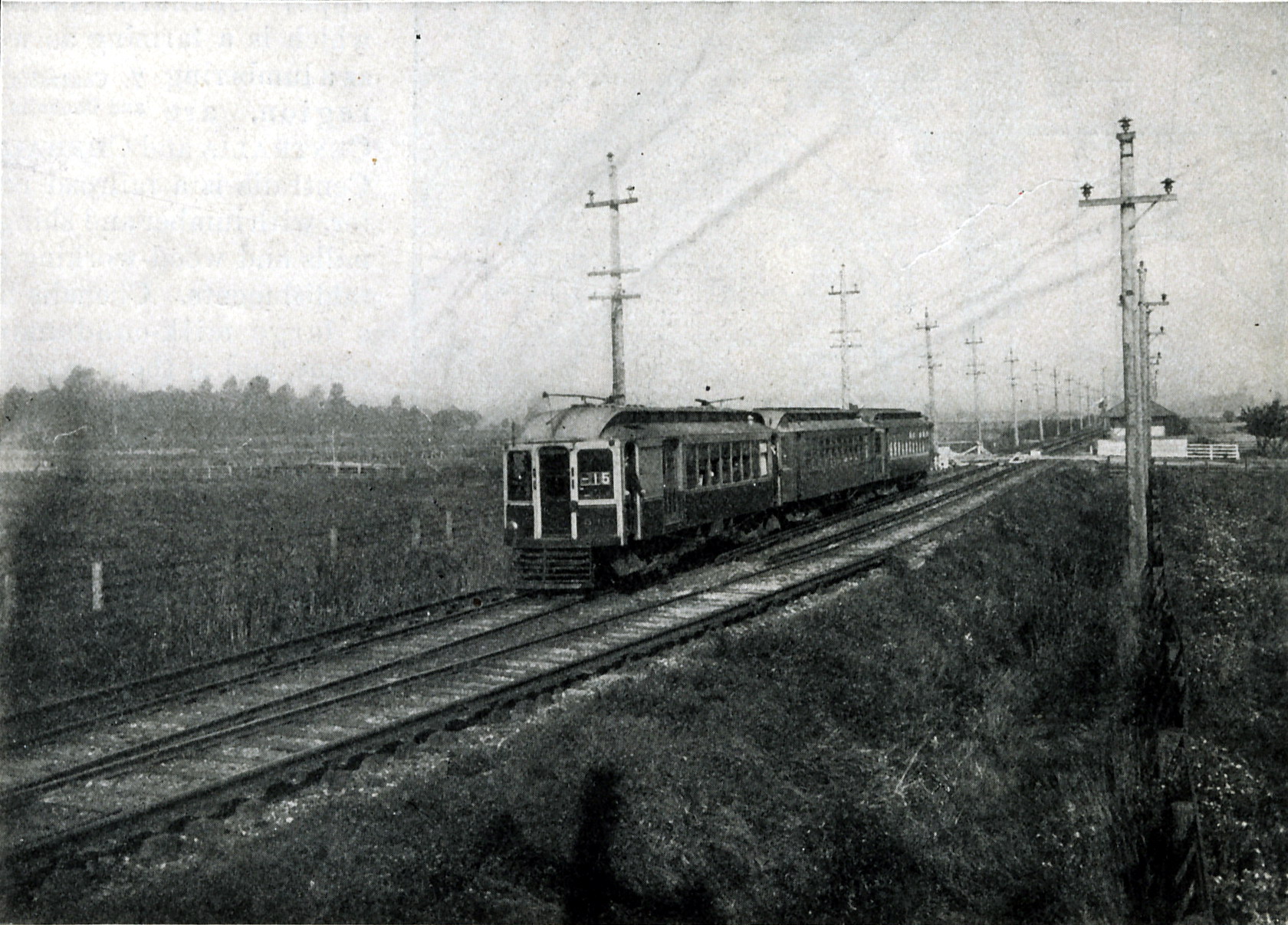

| Westlake Blvd, 1909 (Webster and Stevens) |

The first streetcar line to open was the South Lake Union Line in 2007; it runs from Downtown via Fairview, Westlake, and Terry streets to the suburb of South Lake Union at the Westlake Hub and McGraw Square. The alignment is a Seattle original, as Seattle Electric first opened the line five days after being granted a franchise in 1890. Known as the "Westlake Line" back then, it was privately operated until being absorbed by the Seattle Muni in 1918. Its last train ran on April 13, 1941, and was replaced by buses.

|

| Westlake and Olive, 1949 (City of Seattle) |

Concilman Benson's streetcar was an immediate success when it first opened in 1982, and further improvements in the 1990s stirred interest in creating a new light rail for Seattle. Sound Transit, which operates public transit in Washington state, was already in the process of creating an interurban light rail line from the University of Washington, Seattle to the Tacoma Dome (Link Light Rail) and a municipal extension to the existing Seattle Monorail from Ballard to West Seattle via Seattle Center. Obviously, none of the plans panned out but one managed to sneak through the cracks and onto the desk of Mayor Paul Schell.

Schell, then mayor in 1998, proposed running a new light rail from the University District to South Lake Union (SLU). SLU was originally a massive mill shipyard town, but possessed an opportunity for urban renewal by the late 90s. Paul Allen, Microsoft co-founder, intended the area to be used as a technology hub like Silicon Valley under the name of "The Seattle Commons", but this plan was rejected by voters. Inspired by the Pearl District's revitilization under the Portland Streetcar, Allen knew the streetcar would be a way to revitalize SLU and funded the project through his Vulcan Inc. venture capital holdings.

|

| The George Benson Streetcar, some time in the 1990s (The Seattle Times) |

Mayor Greg Nickels and the Puget Sound Civic Council oversaw groundbreaking on July 7, 2006, with Nichols offering naming rights to each station as a way to gather financial support. The plan was heavily criticized for going way over budget (from $45 million at planning to $50 million at groundbreaking) and by some political activists who preferred the money go to improving road maintenance and bus operations. Construction continued despite more criticism, as some advocacy groups saw Allens' pro-streetcar lobbying as a "billionaire's plaything". The first Czech-built cars would arrive in Seattle in September 2007, with system testing beginning the next month.

|

| The South Lake Union Streetcar takes its first run on December 12, 2007 (Rober Scheuerman) |

The first car ran on December 12, 2007, taking just a year and a half of construction on the 1-mile line. Rides were free at first, then a $1.50 fare was introduced the following January. The streetcar was a success despite the high price tag of $56 million, but it also had a lot of operating teething troubles. The streetcar became labled a hazard, as drivers complained of the streetcars hogging the new one-way alignments on Westlake (south) and Terry (north), and bicyclists tried to sue the streetcar as a safety menace before the case was thrown out of court. Low ridership also plagued the Streetcar, as the Puget Sound and Seattle Electrics both experienced.

Things steadily improved for the streetcar, as businesses began popping up all over SLU. To meet the new demands, the city of Seattle proposed in 2015 to create "transit-only" lanes accessible by bus and streetcar only during rush hours (similar to Trimet and Portland Streetcar's alignments in Oregon). The year after, the new First Hill Streetcar opened, connecting Capitol Hill, First Hill, Little Saigon and Occidental Mall, and one notable feature of it was the paralleling bike lane. However, the two lines were still seperated by over a mile of street and the plan to connect the two was halted in 2018.

In 2017, the two Seattle Streetcars experienced its highest ridership yet, peaking at over 1.4 million people (double what it did the year before). Despite this, the system is still in severe decline due to unreliable service and lacking an effective rail connection between them. Nevertheless, Seattle is on its way in returning the trolley back to its streets and one can only hope King County Metro and Sound Transit both can facilitate that expansion.

|

| The First Hill Streetcar glides onto Yesler Way, tracing the old Cable Car route. (SounderBruce) |

And yes, people call it the "South Lake Union Trolley" because it spells "SLUT". I think we can all stop giggling now.

|

| "I don't care what you call it, as long as you ride it." - Mayor Greg Nickels (Greg Dunlap) |

Teeheehee.

-----

Thank you everyone for keeping up with February's Trolleypostings! My editor, Nakkune, and I've experienced our biggest readership yet since I moved the series over to Blogger with this new format. From both of us, thank you for reading and I wanna extend an apology to King County Metro if I've mistakenly insulted you in this writing. I wanna see your public light rail look good and be worth using, especially the heritage behind it.

Next month, we leave the comfort of the West Coast and make our first foray inland with Arizona's Tucson and Old Pueblo Trolleys! Until then, ride safe!

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13698049/2863.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56738081/capitol_hill_streetcar.0.jpg)